Life doesn’t always work out perfectly. You can make the wrong decisions. You can leave things too late. I wish, though I’m not distraught about it, that I’d had another child, maybe two even, and given my small son siblings.

The tacit assumption was always that children are an obstacle to the noble process of self-actualization

I’ve been thinking about this in the context of our shrinking population — the great global baby bust — and wondering why more women don’t express regrets. Often, for any number of reasons, the decision to have children is out of our control. But even so, there must be many hundreds of thousands like me who wish with hindsight that we’d got a move on, had some or more. Why don’t we say so?

Instead, in every paper and on every screen there’s a constant drip of articles which insist that no childless women wish they’d started sooner and that having only one is a great boon. The single-child family is a popular subject in magazines these days. It lends itself to a color supplement. “One and done” the headline goes, alongside a photo of a smug-looking outdoorsy couple in expensive breathable waterproof jackets, their lifestyle uncompromised, their handy single toddler stuffed into a backpack. The text is invariably a bingo card of all the modern era’s most hellish phrases: forever home, fur-baby, me-time, work-life balance.

I read these articles because I have an only-child, but they leave me disconcerted. I feel that either I’m missing the point, or they are. Yes, of course having just one is easier. They’re cheap to feed and fun to chat to. You can pop them on the back of a bike, hand them over to the other parent and spend quality time with your iPhone. But what’s ease got to do with having children? If ease is your aim, why have kids at all? And why does no one ever mention the only-child situation from the child’s perspective? What if your one child would like there to be others?

I’m not trying to make the mothers of only children feel guilty. There’s no shame in having none or one. It’s just curious, given all the hand-wringing over birth rates, that regret is taboo. Perhaps it’s because although we all face the same predicament, every nation has its own preferred explanation. In some countries the received idea is that childcare is too expensive, in others that women work too much or men too little. In London, for instance, thirty-somethings enjoy blaming property prices. “I would like to have a baby but the costs are too high,” announced a millennial called Charlie Gowans-Eglinton in last Saturday’s Times of London, posing under a spotlight in a feather boa. I wonder if it crossed her mind as she posed to think of all the circumstances in which women around the world do manage to have and enjoy their babies.

I don’t think Charlie’s quite nailed the problem. If the baby bust could be fixed with cash incentives, we’d know about it by now. Desperate governments have offered endless bribes and they don’t work, not here and not anywhere. Singapore has spent hundreds of billions on childcare vouchers to absolutely no avail. Their birth rate hit a record low in 2022 after years of steady decline. Tax breaks don’t kickstart a boom.

All round the world and increasingly, concerned politicians and statisticians scratch their heads over demographic collapse. Pro-natalist events are becoming oddly fashionable, publishers hunt for “big idea” books with catchy baby bust headlines.

No one seems to be examining why so many women like me are simply leaving it too late. There’s no market for it. And if women are leaving it too late, instead of this hysterical attempt to pretend that every life choice is always for the best, isn’t it a good idea if women are encouraged to be honest?

In odd moments in the pub and in confidence, women do sometimes talk of running out of time. But that deprives us of agency. You have a choice as to how you spend your time. My twenties and thirties I chose to spend with friends: going to the pub and falling off my bike; traveling; working on this magazine. It didn’t occur to me for a moment to get serious about the dating game or to try to settle down. I had no idea it might ever be too late, though it nearly was. By the time my son was born I was forty-one. I feared for my job and my knees and I didn’t set my sights on more.

I love my small family. I’m lucky to have it. But if I could take back some of that time and spend it in other ways, on having another baby or a chance to watch my grandchildren grow up, I would. And if women like me never say that, how will future generations ever know?

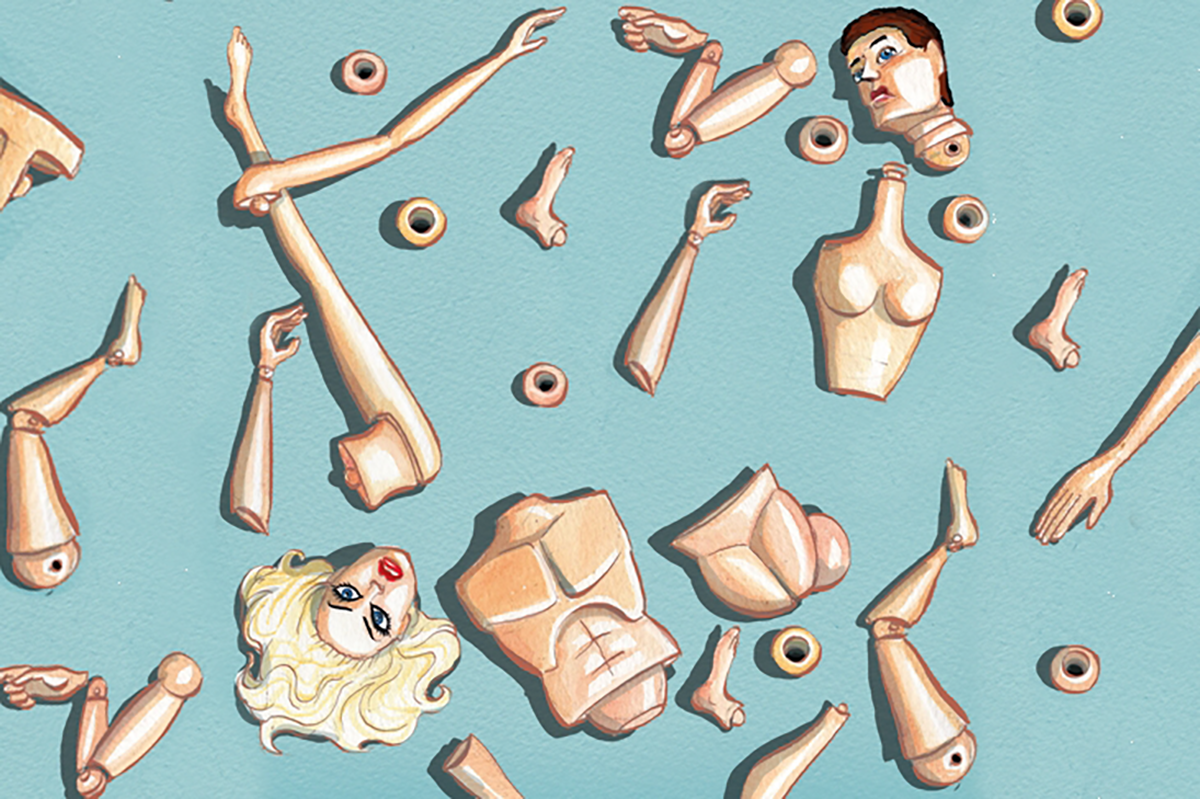

Why did I dawdle for two decades? I’ve been casting my mind back to my school days and I find echoes of that one-and-done philosophy throughout. In sex ed, the tacit assumption was that same “one-and-done” philosophy; that children are an obstacle to the noble process of self-actualization. In the weekly hour devoted to reproduction we were told only that pregnancy is a blight to be avoided — nothing about the enormity and privilege of having a child, certainly nothing about the fact that fertility rates are plummeting and that getting pregnant when you’re older can be a major chew.

In school, sex was presented as a glorious gift given to us by the 1960s, and pregnancy as something to be avoided at all costs; abortion as a cause for great celebration. Only rarely did anyone express a different view. I remember one evening in the hall of our family house when I was twenty-odd, my mother saying quickly and almost in passing: “If you do ever get pregnant by mistake, darling, keep the baby. I’ll look after it.” I was horribly embarrassed, keen to get out of the door, but I also felt a flicker of something oddly like joy, which I soon forgot.

For generations now, nearly a half-century, children have been taught that life has value only in as much as it’s convenient. I don’t think it’s crazy to see the roots of the current demographic crisis buried here.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.