For the past seven and a half decades Western politicians have been exhorting voters to ‘believe’ or ‘have faith’ in democracy. They should have been addressing themselves instead. The unpleasant truth is that 20th- and 21st-century politicians on the right have never believed that constitutional democracy based roughly on the American model could ever satisfy the masses by giving them the material loot and freedom they expect, while those on the left have always thought it does not go far enough in granting themselves the power and authority they require. Thus conservative governments, lacking confidence in their fundamental principles and the durability of their political achievements, have governed timidly and defensively, while liberal or outright leftist ones have acted boldly and aggressively. In short, the prevailing assumption, left and right, has been that the natural historical trend is leftward and will remain so for the imaginable future.

The social, economic and political activism of the 1930s strengthened the seemingly natural alliance between conservative political parties and big business, in the USA especially. That alliance persisted after World War Two and through the 1980s, the golden age of corporate conservatism in America.

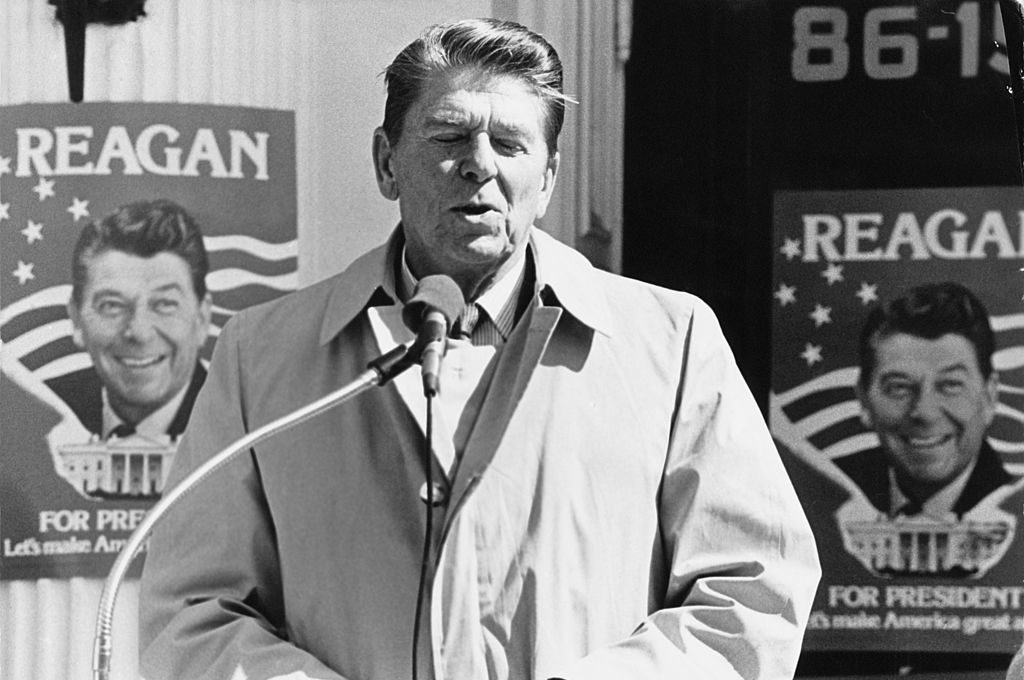

Throughout these decades the Republican party’s political interests and corporate America’s financial ones largely coincided, to the satisfaction of establishment conservatism for which malcontents on the Old, or traditional, Right had not yet invented the rude and ungrateful name Conservatism, Inc. After Sen. Goldwater in his campaign for the presidency in 1964 was run over and left for dead by Lyndon Johnson’s political machine, ‘right-wing extremism’ (the establishment assumed) had at last gone the way of Jefferson Davis, Johnny Rebel and the Peculiar Institution and the Republicans’ future seemed assured. While their confidence was unwarranted, two decades later the considerable accomplishments of President Reagan’s eight years in the White House were judged so considerable, and conservative ideas so effective in practice, that consensus on the American Right seemed assured.

In fact, neither Conservatism, Inc. nor popular conservatism had overcome the self-skepticism and pessimism that had weakened it since the 1930s. One proof of this was the arrival of neoconservatism in the 1970s and its development, nurtured by Reagan, into a powerful ideological movement. Another was the challenge of so-called ‘populist’ conservatism during President George H.W. Bush’s four years in office and the ‘compassionate conservatism’ announced by his son following the Clinton interregnum.

Unlike the neoconservatives, who made no secret of their intention to reform Republicanism as an alternative Democratic party, the populists proposed — with equal candor — to return conservatism to what they understood as its quintessentially and uniquely American roots. The neoconservatives, most of them people with academic backgrounds and a belief and confidence in ‘experts’, technique and the managerial state, were — as they remain today — elitists skeptical of popular democratic government, save for the legal protections and the social support it provides. Only the ‘populists’, trusting to the soundness of popular instincts and common sense, sincerely believe in rule by the people — in other words, in democracy as the Framers of the Constitution envisioned the thing. Though liberals would find the proposition absurd, the truth is that the government best suited to constitutional democracy is conservative government.

Perhaps without knowing it, the bulk of American conservatives have gradually moved from coexisting with liberalism to compromising with it, to secretly preferring it to conservative political philosophy and conservative government. Historically the modern world has been a liberal world, where acquiescence in liberal principles and ways of thinking, feeling and behaving is easy, the path of least resistance. Liberal laws, rules, precepts, morals and mores have reshaped western societies in ways that make resistance to almost everything unnecessary, and created a culture at the elite, as well as the popular, level that simultaneously expresses and justifies itself. Lastly, the longstanding social and occupational hierarchy that for centuries had determined occupational ranking and social status has been abruptly replaced over the past generation or two with a very different, almost an inverted, one.

All these things explain why the corporate conservatism that prevailed in boardrooms from the 1950s through the 1980s has given way to progressive liberalism, while small-business conservatism remains loyal to the Republican party. Unless it transforms itself very rapidly indeed, the GOP can never be glamorous, fashionable, ‘cool’, excitingly unconventional, freethinking and iconoclastic — and at present it shows no sign of having a will to do so, supposing it actually could.

Previously, corporate America took pride in its political, economic and social conservatism, its Brooks Brothers stolidity and resistance to fashion of every kind. In the postmodern and postindustrial world of muddled and uncertain social categories, status is what counts most for educated professional, business and managerial people and for those with careers in politics and government. Men of business have always been obsessed with respectability — and today conservatism is no longer respectable at top of the western social pyramid, as the corporate CEO is no longer the model of success in America or elsewhere, his role having been usurped in the popular imagination by the celebrity entertainer, the sports star, the digital pioneer and the progressive politician.

Even so, the straitened situation in which political conservatism finds itself has the potential to be a self-correcting one, owing to a social phenomenon no one imagined or foresaw. It is the extent to which business corporations are transferring their interest from mass markets to progressive politics that has at best a minority constituency, even as Republican politicians are discovering market politics. American progressives show little interest in attracting new voters and expanding their base. Instead, they are concentrating on ramming their agenda through Congress and the White House by twisting the arms of their colleagues. The left appears to have little care for national popularity, if only it can control Washington.

By contrast, while what remains of the old Republican party, unreformed by Donald Trump, is trying to return to its former self, the new Republican party — the party of Trump — is responding to the concerns of its natural constituency to a degree unprecedented in recent American political history. It is paying close attention to what conservative Americans want and trying to give it to them, often — one suspects — at the expense of their own political preferences. If this is indeed what is happening, the results should be the same as if the new conservative politicians truly believed in constitutional democracy; especially if, by pretending to respect it and observing its rules, they develop a genuine appreciation for its virtues.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2021 World edition.