Does anything say “June” quite like strawberries and cream? The sweetness of sun-ripened strawberries allowed to remain on the plant until peak maturity, pairs exquisitely with the velvety, ever-so-slightly tart, richness of cream. Taste-wise, it’s a perfect match — and looks-wise, strawberries and cream are one of the prettiest dishes of summer. Some things are just meant to be.

But life isn’t all strawberries and cream. Sometimes you have to shake things up with a lively new take: Gorgonzola and white chocolate cheesecake, for instance, or lamb with anchovy, garlic and rosemary. Love it or hate it, at least you’ll have your diners sitting up and paying attention. And sometimes a bit of experimentation can lead to a new favorite. That’s the story behind salt and caramel. In 1977, chocolatier Henri Le Roux and his wife opened a pâtisserie in Brittany. He quickly realized he needed a specialty that would set his shop apart from the competition and decided to use the famous salted butter of the region to make caramel. It was an instant classic. Le Roux was soon awarded the “Best Sweet in France” prize and had to register a trademark to discourage copycats. Today, salted caramel has earned an enduring spot in both the cooking canon and the ice cream freezer.

What’s known as flavor-pairing theory was first proposed in 1992 by celebrity chef Heston Blumenthal and chemist François Benzi. According to these luminaries, most of the subtleties of flavor are detected not by the taste buds but by receptors in the olfactory organs. Every food gives off a unique aromatic profile, made up of hundreds (in some cases) of volatile organic compounds. Flavor-pairing theorists say that ingredients with a lot of compounds in common will pair successfully, no matter how outrageous their juxtaposition may seem at first blush — for instance, coffee and chocolate with garlic, or oysters and passion fruit.

This chemistry-based approach guided Blumenthal in the wild and occasionally wonderful signature combinations he served up at his famous modernist restaurant the Fat Duck: caviar and white chocolate, caramelized cauliflower and cocoa, eggs and bacon ice cream, salmon with licorice.

There’s a corollary: if delicious pairings are a result of chemical analysis, rather than creative flair, then computers should be better than humans at inventing new recipes. FoodPairing AI has been marketed for some years to food-processing companies, to help them come up with new, attention-grabbing combinations that can be the next big seller. AI was recently credited as the inspiration for a new type of Pringles flavored with roast beef and mustard (how original! Or should we rather say, how dispirited and warmed-over sounding!). Robot mixologists are out there too, whipping up martinis and custom G&Ts. Royal Caribbean Cruises premiered the Makr Shakr in 2014, which could whip up 120 cocktails per hour with perfect precision. There’s been a lot of so-called progress since. Recent models are being developed which will identify customers, offer them their “usual” and make small talk — a truly horrible notion, as if chatting to another human being across the bar were in any way comparable to coping with a self-checkout register, or fighting your way past an answering machine: “FOR SALES AND SERVICE, DIAL TWO TWO SIX.”

Unlike the commercial world, the scientific community has not accepted flavor-pairing theory peacefully. It’s a “European fad,” says Maurits de Klepper, lecturer in gastronomy at the University of Amsterdam; “the experience of flavor is much more complex than any such simple approach,” says Charles Spence, researcher in psychology at the University of Oxford, and “it’s ridiculous… a gimmick by a chef who is practicing biology without a license,” says Harry Klee, who, as professor of horticultural science at the University of Florida, specializes in tomato flavors.

Even Blumenthal would eventually distance himself from the trend he did so much to promote, telling the Times of London in 2010: “Looking back at my young- er self I’m almost embarrassed… I now know that a molecule database is neither a shortcut to successful flavor combining nor a failsafe way of doing it. Any foodstuff is made up of thousands of different molecules, that two ingredients have a compound in common is a slender justification for compatibility.”

And of course it doesn’t make sense for something so expressive of human culture, emotion and artistry to be reducible to the purely chemical — just as it doesn’t make sense for joy, suffering or excitement to be mere chemistry and not a complex combination of physical and spiritual.

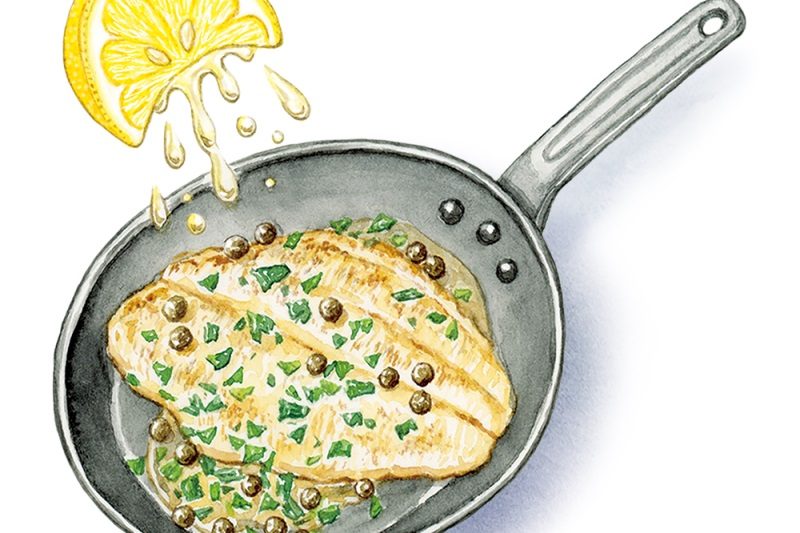

Yet there’s a magic to a successful new combination, or an old combination artfully done, and if inspiration came from chemical analysis, why not? The proof is in the pudding. Niki Segnit’s Flavor Thesaurus is a gift to the kitchen, wasting no time on theory and getting straight to what tastes good with what: blue cheese and avocado, mushroom and anise, watermelon and tomato.

Forcing things together isn’t magic, though — it’s just trying too hard. Into this category falls some of the more modernist cooking and so-called “molecular gastronomy” that thrives on the idea of eating as “experience” rather than nourishment, refreshment or celebration. They’ll have you inhale essence of decomposing forest floor before serving a lone foraged mushroom, followed by a giant frozen kernel of reconstituted corn that looks like it fell from space (why?). Then headphones emitting recorded sea-noises are slipped over your ears as the oysters appear — just as silly, and as unsatisfactory, as linking a recording of a gas engine to the accelerator of an electric car or thinking that anyone wants to hear small talk from the robot behind the bar. Surely giant lizard people, not humans, came up with these strokes of brilliance.

This is the school of thought — and Heston Blumenthal actually did this — that needed to run an experiment in order to discover that people would rather eat a foodstuff called “frozen crab bisque” than the same thing labeled “crab ice cream.” Of course they would. A child could have told him so.

So could the suitor in the nursery rhyme, who had more sense than to woo Curly-Locks with male feminism and promises of parsnip gel globules on a bed of dehydrated watercress. No dishes or hard labor for his wife, only comfort and refinement: she would “sit on a cushion and sew a fine seam/ And feed upon strawberries, sugar and cream.” Winning words, and a winning pairing. Hopefully she said yes.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s June 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply