In 146 BC, Scipio Aemilianus laid siege to and destroyed the city of Carthage, thus bringing the third Punic War to an end. Scipio made a gift of what remained of the Carthaginian library to the kings of Numidia, Rome’s old ally against Carthage. At the direction of the Senate, however, he held back one book, the agricultural treatise of Mago, which he sent back to Rome. It was duly translated into Latin, but all that remains are fragments, which is too bad, for Mago apparently had a lot to say about many exigent matters, including the cultivation of grapes and making of wine. It appears that it was the Phoenician precursors of the Carthaginians who, around 1500 bc, first planted grapes in the Iberian peninsula. (The Latin word for ‘Carthaginian’, by the way, was pūnicus, which is why we speak of the ‘Punic’ and not the ‘Carthaginian’ wars.)

I thought about that prehistory recently when visiting a couple of Manhattan’s premier tapas bars, Alta, on West 10th Street, and Casa Mono, on Irving Place. The Carthaginians were apparently skilled farmers. That old grouch Cato the Elder, famous to schoolboys trying to get outside the gerundive, not only ended every speech with the directive Carthago est delenda, but he was also in the habit of reaching into his toga while regaling his audience and pulling out some plump and delicious-looking figs: ‘These luscious fruits come from Carthage, which is only two days sailing from Rome!’ he warned.

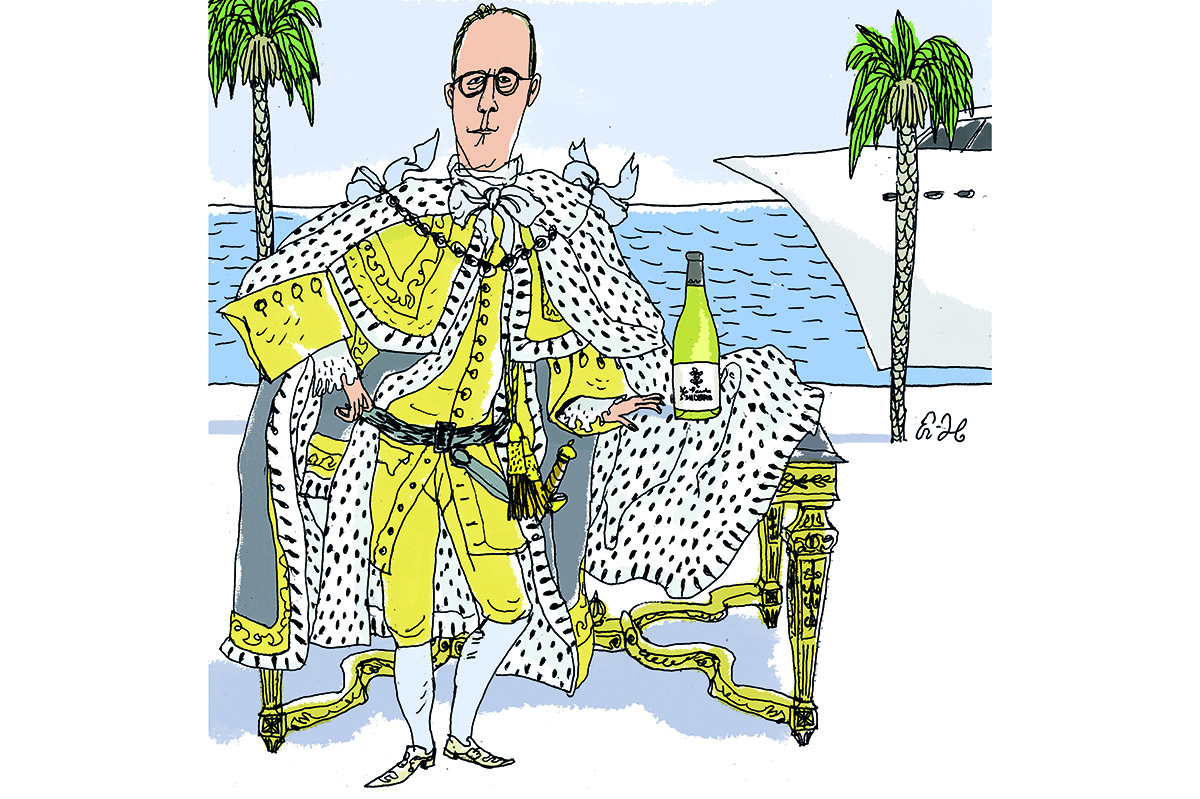

Cato thought that vineyards were the most important part of a farm, which makes me think kindly towards him, but I think I would have preferred to be accompanied by Scipio on my visits to Alta and Casa Mono (I would have insisted that he bring along his secretary-hostage, the Greek historian Polybius, who was with him at Carthage in 146). I feel sure that he would have liked the food, which was delicious at both establishments, and I am likewise confident that he would have enjoyed the wines from Ribera del Duero in north-central Spain, one of the country’s premier grape-growing regions, about two hours north of Madrid along the Duero River.

At Alta, which occupies a fetching 19th-century townhouse full of romantic private rooms, the star of the evening was a 2013 Convento San Francisco. From a small, modern vineyard of about 100 acres, this wine had its first vintage in 1998. Tempranillo is the great grape of Spain, powering Rioja and many other wines. Convento San Francisco is 90 percent Tempranillo and 10 percent Merlot. The name ‘Tempranillo’ is the diminutive of temprano, ‘early’, so called because the grapes tend to ripen a few weeks earlier than other varietals.

It is a famously food-friendly grape, and the 2013 Convento San Francisco was showing very well: clear, elegant, lapidary, it was nonetheless sensuous and delectable. It reminded me a bit of Pyrrha as described by Horace in ‘Ode 1.5‘ (‘O gracilis puer’). It had the same simplex munditiis, ‘innocent neatness’, that Pyrrha exuded, but it also inspired similarly alarming questions: cui flavam religas comam: ‘for whom are you arranging your golden locks now?’ Such inquisitiveness is a good thing in wine, if not mistresses, and for $35 or so you won’t want to miss out on the treat.

Another night, Scipio and I made for Casa Mono, a much-celebrated restaurant (three stars from the New York Times in 2015, a Michelin star every year since 2009). The vinous star that night was a 2017 Malleolus from the distinguished bodegas of Emilio Moro. The name malleolus is Latin for ‘small parcel’, which describes the source of the grapes. The wine is 100 percent Tempranillo and in the 2017, a notably small-yield vintage, it has a deep and powerful succulence, full of dark, jammy fruit yet still pairing brilliantly with food. Pyrrha really let her hair down for this vintage.

A quick check suggests that Malleolus from 2017 or 2018 will set you back somewhere around $40-$45, a steal. You’ll note when you get a bottle that there are little bumps on the label. They’re Braille. Since hosting a charity event for the blind six or seven years ago, the Moro family decided to underscore their commitment to the cause by including Braille lettering on all their labels. It often happens that such concessions to a cause are slightly off-putting — at least, I am often off-put by them — but somehow this gesture was so understated and unobtrusive that it only makes me feel fonder of this really excellent new discovery.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2021 World edition.