I never intended to spend Christmas 1989 on a short break in Bucharest. I had enjoyed a long, thrilling autumn in dark, sad cities in eastern Europe, running and marching with ecstatic crowds as they overthrew communism. But this had all been in the calmer, less exotic regions of the Warsaw Pact, where dumplings were on the menu, passions were equally stodgy, and both rebels and governments would rather hold press conferences than open fire on each other. I was in lovely but dreary Dresden when news came that Nicolae Ceaușescu’s baroque dictatorship was tottering, and my foreign desk urged me to head to Hungary and on into Romania as soon as the border opened, if it did.

Air travel was impossible. It had to be by land. At Szeged in Hungary I came to the edge of the known world, gazing across the closed frontier post into the dark exotic chaos so well described by Olivia Manning in her Balkan trilogy. I knew no Romanian. I knew nobody in Romania. I knew next to nothing about Romania. But the main thing was that I was there — and then the border opened. More crucially, I had the permission of Mrs. Hitchens to cross it (I confess I more than half-wished she had forbidden me to go, but she never stood in the way of any adventure). I crossed into Arad, where I changed the last of my money into a wad of Romanian lei, literally the softest currency I have ever met. The notes were worn from use into limp, porous purplish rectangles whose value was hard to make out. And, despite a fair amount of Balkan wailing that the Securitate secret police would come in helicopters and machine-gun me if I did so, I bought a first-class ticket for the Bucharest Express which was expected on time and duly turned up. So much for the panic-spreaders.

As soon as the rusty train heaved itself on its way, I was in the grip of romance, reminded of Kay Harker’s journey among bleak hills in the strange low light of December, in that marvelous story “The Box of Delights.” Kay looks up at the hills from the train window, and thinks: “It was a grim winter morning, threatening a gale. Something in the light, with its hard sinister clearness, gave mystery and dread to those hills. “They look just the sort of hills,” Kay said to himself, “where you might come upon a Dark Tower, and blow a horn at the gate for something to happen.” I have always known what he meant.

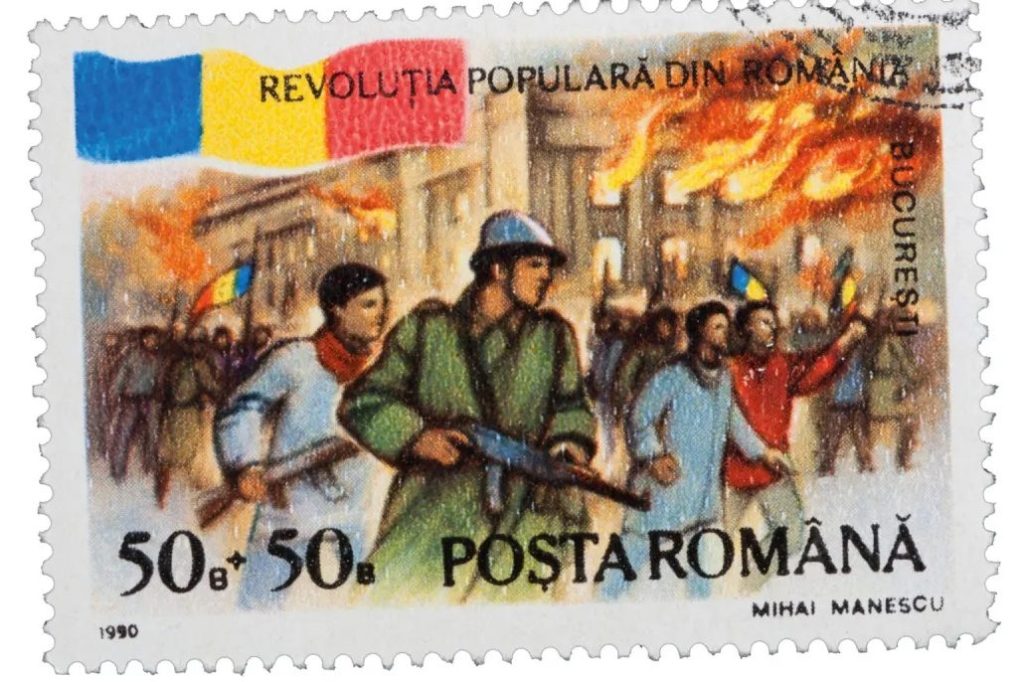

What seemed to be a firework display began on the street outside. It was not fireworks. It was machine guns

Since my boarding school days I have loved long train journeys round about Christmas, though I prefer them to be homebound ones — what F. Scott Fitzgerald beautifully described as “the thrilling, returning trains of my youth and the street lamps and sleigh bells in the frosty dark and the shadows of holly wreaths thrown by lighted windows on the snow.” As the short day darkened, I saw shepherds, cloaked and hatted in thick sheepskin, actually watching their flocks.

I was in truth quite worried, but I had decided to take the risk and there really was not much to do except eat the cheese sandwich I had bought at the station. I encountered an Australian journalist in a long leather coat who seemed to be an old Romania hand. He was certainly an older Romanian hand than I was. He told me which Bucharest hotel to head for, and how to get there by underground train. Then he told me it was probably a good idea to run in a zigzag pattern from the tube station to the hotel, as there might be snipers. He may have been having me on. I do not know what happened to him and have never seen him since. I sometimes wonder if he was in fact an apparition or a hallucination. But I duly zigzagged through the falling snow, and was not sniped at. Pah, I thought, so much for all that whimpering and wailing about the Securitate.

It was by now late on Christmas Eve. My office would be empty, as Fleet Street does not publish on Christmas Day. Embarking on my first major bribe, I gave the hotel switchboard supervisor a large carton of Kent cigarettes, the country’s real currency, and asked for a call to my Oxford home. “Go to your room and wait,” she said, as they always did in such places in those days.

I went to my room and waited. I began to tap out some sort of story that might be usable on Boxing Day, when what seemed at first to be a firework display began on the street outside. It was not a firework display. It was machine-gun fire, much of it very obviously tracer bullets, whizzing past my window. I am no hero. I did not fancy having my obituary in the December 26, 1989 issue of the Daily Express, with my name probably misspelled and an unflattering blurred picture beneath the headline EXPRESSMAN DIES IN ROMANIA. So I switched off all the lights, pulled the curtains tight, shoved the heavier furniture towards the window and slid under the bed (I was slender enough to do this in those days). There were lulls, but the gunnery continued off and on.

During one of the breaks, the telephone shuddered, rattled and tinkled. I pulled the receiver under the bed with me and answered. Mrs. Hitchens was on the line. She had finished hanging up the children’s stockings and leaving out the carrots and wine for Father Christmas and his reindeer. The tree was all done. I was glad to hear it, though at that point these sweet things felt as far away, and as unreachable, as the moon. How was Bucharest, she wished to know. Oh, quiet, I replied. Nothing much to see. Whereupon the Kalashnikovs and the big heavy machine-guns started up again, so unmistakably that I had to stop lying to her.

Perhaps anxious that my possibly fatal trip should not pass unrecorded, she urged me, there and then, to dictate a report to her which she would pass on to the foreign desk. And through the noise of gunfire I began “This is the real-life country where it is always winter and never Christmas…,” and from then on it all flowed quite smoothly.

The next few days passed in a succession of horrors and fret. Christmas Day was worse than most days: the desperate, stinking hospital wards full of wounded people, the judicial murder of Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu, their gory corpses displayed on TV, the visit to their office (during which I looted Elena’s red document holder, which I still possess, from her desk).

And then the day of release, when a colleague miraculously arrived to take my place. There were still no flights, so I went back to the great dingy North Station just in time to see an immensely long train, painted the color of pickled cucumbers, the favorite shade of the communist world, begin to move. Not caring where it was going, as long as it was not going to Romania, I flung my bags aboard and leapt after them. As it happened, it was carrying an entire Soviet orchestra to Sofia in Bulgaria. I will never forget their kindness to me, making space for me to sit, sharing their vodka, their black bread and their sausage as the train wound through the blue mountains of the Bulgarian border country in the twilight and then down into Sofia, which after all my adventures felt like Paris. So much for short breaks in Bucharest. We had our proper Christmas late that year, and it would not be the last time that would happen.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply