This is my last week in the Alps and I’m trying to get it all in — skiing, cross-country, kickboxing, even some nature walking along a stream. (I did my last downhill run with Geoffrey Moore, one that ended in a collision with a child at the bottom of the mountain, and I’m thinking of calling it quits on the downhill-skiing front.) The trouble with athletes is that we early on enact the destiny to which we are all subject, an early death. The death of sports talent is a subtle process. The eyes go first, then the step falters. Eventually you feel like an old man who is not in the same league as his opponent. I was lucky to get old late — in sport, that is.

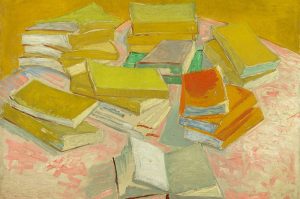

Presently, reading takes up lots of my time, whereas before it was sport and the pursuit of the fair sex. I mostly read history. I rarely read novels — and with very good reason. There’s nothing a novel can teach me nowadays because I’ve seen it all firsthand. And worse, because of my age and experience, at times I can feel the novelist straining, whereas in my teens everything I read in fiction was new and believable. And novelists sure were glamorous back then, tough and terrific. In my young mind they were all heroes. They had no dandruff, they were not pallid, enfeebled weaklings, and they did not scribble neurotic reminiscences about their mother or about being sexually abused.

Let’s take it from the start: after learning the Greek classics and myths as a boy, at fourteen came The Catcher in the Rye. I was certain that Holden Caulfield was based on me, as were 300 other boys in boarding school convinced that J.D. Salinger had somehow infiltrated their inner selves. It was a work of lasting value that confirmed to me that a novelist knew more about me than I myself did. The novel was a technical masterpiece with a disturbing consciousness at its center. It is a truer book about adolescence than, say, David Copperfield, yet I never dreamed of catching children running in the fields of rye and saving them from falling over. Afterwards I read From Here to Eternity, for the sex parts, but I also learned from it that duty and bullying are not confined to boarding schools. (Later on in life I interviewed and became friendly with James Jones, a wonderful, tortured man and a tough guy.)

Then it happened: I read Tender Is the Night at fifteen, and my life changed forever. The glamour, decadence, beauty and drama of Dick Diver’s life and that of his playground, the French Riviera, made up my mind once and for all. Those were the type of men and women I wanted to be with — and to hell with bores who went to the office and were respectable. Fitzgerald was my hero, and then I read Hemingway.

He courted danger, bedded beautiful women, drank and got into fights. I read what grace under pressure meant when I discovered a short story by Papa, “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.” I couldn’t wait for school to finish so that I could hit the French Riviera and Paris, and I did. I also ran the bulls in Pamplona but never met Papa. The behavior of men under stress was an endlessly fascinating topic for Hemingway, and conquering one’s fears became all-important according to Papa’s dictums.

Bereft of purpose as I was at fifteen, the novel became central in my life. John O’Hara’s Appointment in Samarra defined WASP America, their good manners and honorable behavior hiding their insecurities and uptightness. Just before being exiled to the Sudan and Egypt where my father had textile factories, I read Larry Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet and never has an exile been more pleasant. I got to Alexandria ten years too late but still got a whiff of the decadence.

One night in New York I was introduced to a young novelist by the name of Norman Mailer. His novel An American Dream taught me to defy authority and to doubt experts. We stayed friends for the rest of his life, and I inherited his son Michael. I wrote a fan letter to Irwin Shaw and we skied and played tennis and discussed the Wehrmacht, which he had seen from up close.

Three English friends who all committed suicide — Mark Watney, Dominick Elwes and John Lucan — were straight out of Evelyn Waugh, but I learned more about the English from Anthony Powell’s Dance than from Waugh. And I still regret, as a twenty-year-old, turning down an invitation to La Mauresque where I was to meet the great man, Somerset Maugham. The invite was from a promiscuous homosexual and I was worried that the great man might proposition me. I was a fool. Maugham is, to me, one of the best, and the fact that he is no longer relevant is proof of how low our standards have fallen.

So there you have it, the education of a young man by proxy. I liked Nancy Mitford’s stuff but learned nothing from it I didn’t already know. The reason the young today are such weenies is the novels they read. Try some Hemingway, you weaklings.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2022 World edition.