Driving home through Kent the other day, I was struck by how much the topography has changed. When I was growing up there in the 1970s, first in Rolvenden and then in Hawkhurst, there were hop gardens. Today there are vineyards.

I’m not sure Alfred Jingle would recognize the county about which he stated in Pickwick Papers: “Kent, sir — everybody knows Kent — apples, cherries, hops and women.” The apple and cherry orchards are not nearly as numerous as they were in either his day or mine, and the hop gardens have largely, although not entirely, disappeared. As for the women, I can’t vouch for their numbers, but I’m delighted to report they remain very easy on the eye.

I loved picking hops. We youngsters would fortify ourselves with doorstop sandwiches stuffed with sizzling Kent Korker sausages (still made by the Hoad family in Rolvenden) and join vast families of East Londoners down from “the Smoke” for a fortnight of beer, cider, general hilarity and plenty of bloody hard work.

Our job was to collect the stray tendrils that littered the ground of the hop gardens as they were harvested and throw them into the trailers. Although impossible to describe, the heady, spicy, oily smell of a freshly picked hop, rubbed in the hand, is unforgettable. We would stuff the occasional bunch into the fenders of our parents’ cars and whenever we passed similarly adorned vehicles we would toot to each other and wave. Hops in the fender were badges of honor. They declared proudly that we belonged to Kent, God’s chosen county, unconquered by King William in 1066, a quirk of history that has long been commemorated by the county motto, Invicta: “unvanquished.”

It’s a special place, Kent, and its wines are special, too. There are some fifty or so vineyards in the county, producing exceptionally fine fruit, largely for making sparkling rather than still wines. The chalky soil and the benign climate are near the same as those of Champagne, barely a cork’s pop across the Channel, and Kent’s fizz is ridiculously good. The finest comes from producers such as Chapel Down near Tenterden; Hush Heath Estate near Staplehurst; Gusbourne Estate near Appledore; Biddenden Vineyards near, erm, Biddenden; Simpsons Wine Estate near Barham (with probably one of the finest vineyard views of all, with its distant prospect of Barham church tucked between rolling downs); and Herbert Hall near Marden, where vines sit on what was once the Hall family’s hop garden.

Even Nyetimber, the UK’s best-known sparkling wine producer based in West Sussex, now boasts vineyards in Kent, so sought-after are the county’s grapes. It tickles me that Sussex’s most famous fizz needs Kentish oomph to make it sing.

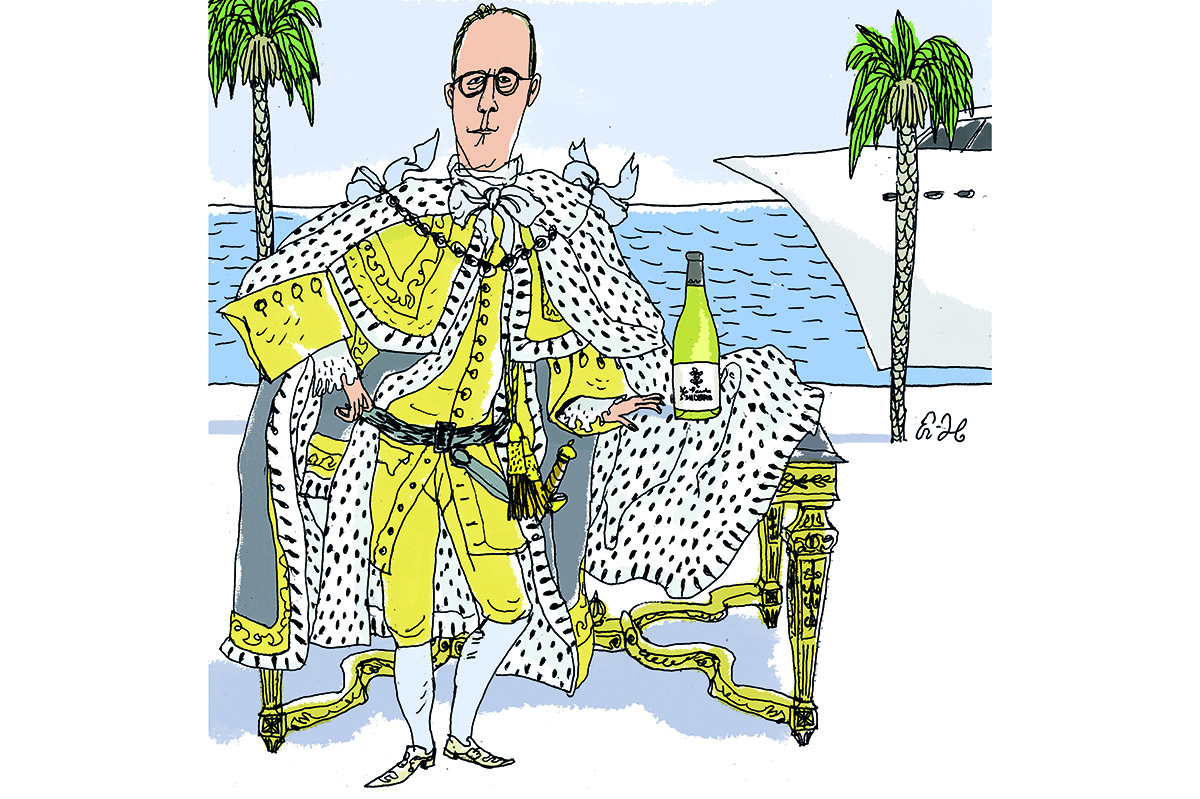

Said vines are up at Chartham Downs near Canterbury. Oh, and guess who else has planted a vineyard there? Taittinger, one of the finest names in all Champagne. It’s named its estate “Domaine Evremond” after Charles de Saint-Évremond, a French soldier and essayist who’s credited with popularizing Champagne in seventeenth century London.

William the Bastard didn’t conquer Kent in 1066, and Taittinger won’t conquer us now. Kent, though, might one day conquer Champagne.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2022 World edition.