Think of Mallorca and what do you picture? Maybe it is elegant tapas bars in the Gothic quarter of Palma, full of yachties and foodies from across the world. Maybe it is literary pilgrims trekking to the house of Robert Graves or noisy parties of Brits and Germans, squabbling over sunbeds in Magaluf.

In one Japanese town, residents have erected a screen to block a much-prized view of Mount Fuji

Any which way, what you picture is tourists. Lots of tourists. So many tourists that the reality of Mallorca as an authentic place is quite obscured, invisible under the weight of visitors. And if you think that sounds bad, so do the Mallorcans, which is why they are finally — perhaps belatedly — rebelling. Recent weeks have seen unprecedented protests against the tourist industry, with thousands of locals marching against the crowds, along with dire promises to “storm the beaches,” unless someone does something.

What might that something be? Some years ago, after witnessing the impact of Chinese tourism on the global travel market, I wrote about the inevitability of some kind of future “rationing.” These pressures were evident in beautiful Taormina, Sicily (featured in season two of The White Lotus), where the crush of tourists was so intense that people were queueing simply to get into the town, then queuing to have their photos taken in the exact same spots. In the Maldives, hotel managers quietly told me that they had so many Chinese tourists and also, increasingly, Russians, Arabs and Brazilians, on top of the traditional Brits, Germans, Americans, that they operated tacit racial quotas. To prevent their hotels becoming overly dominated by one particular ethnicity, they capped each country at a certain percentage of rooms. The hotels were, nonetheless, all near 100 percent occupancy.

Since I wrote that article, and after the significant interruption of Covid, the situation has worsened. In the past two years tourist numbers have vigorously rebounded, and — as in Mallorca — so have the protests against them.

Take Japan. The Land of the Rising Sun is increasingly attractive to tourists, partly because it is also the Land of the Sinking Yen — these days once-pricey Tokyo is about as expensive as Lisbon. The result is a lot more tourists — so many that in one town residents have erected a screen to block a much-prized view of Mount Fuji looming over a convenience store. Why? Because the crowds got so bad that a woman was hit by a car. The view has gone and likewise the madding crowds. For now.

The same phenomenon can be seen across the world. In Barcelona, city-center residents have long complained that their favorite bus is always crammed with tourists visiting Antoni Gaudi’s celebrated Park Guell, making daily life near impossible. Now they have the bus to themselves after the city council secured the removal of the route from Google and Apple Maps. “We laughed at the idea at first,” says César Sánchez, a local activist. “But we’re amazed that the measure has been so effective.”

In Sardinia, home to the Costa Smeralda (a pretty chunk of Med littoral beloved by billionaires), you have to book a spot on the best beaches beforehand. In Seville, authorities are similarly mulling a ticket for non-locals to enter Plaza de España — that’s like ticketing to get into Times Square. Meanwhile in Portofino, on the Italian Riviera, there is a fine for anyone who lingers to take a selfie, i.e. tourists. In Amsterdam and Prague, anti-cheap-tourist ads are planned. As for the dainty island of Bréhat in Brittany, summertime trippers are brusquely capped: 4,700 are allowed in, per day, and after that the island is shut.

In Portofino, on the Italian Riviera, there is a fine for anyone who lingers to take a selfie

Will these deterrents work? Can you stop the mighty juggernaut of the global tourist industry with awkward selfie-bans, crude limits on numbers and some earnest, go-away advertising? I have doubts, mainly because tourism is so enormously lucrative. Last year, global tourism generated about $6 trillion. Worldwide it is perhaps the fourth biggest “industry.” At least 150 nations on the planet cite tourism as one of their top five earners. For quite a few countries it is number one.

What’s more, as global tourism numbers finally exceed the pre-pandemic peaks of 2019, there is no sign of this surge decelerating. Why? Because vast swathes of humanity are only now entering the middle classes, acquiring a passport and gaining the leisure time that enables them to travel. And, of course: good luck to them. The Chinese worked hard for that privilege, as the Indians are working hard now. China became the world’s biggest source of tourists in about 2010 and where it leads India will follow.

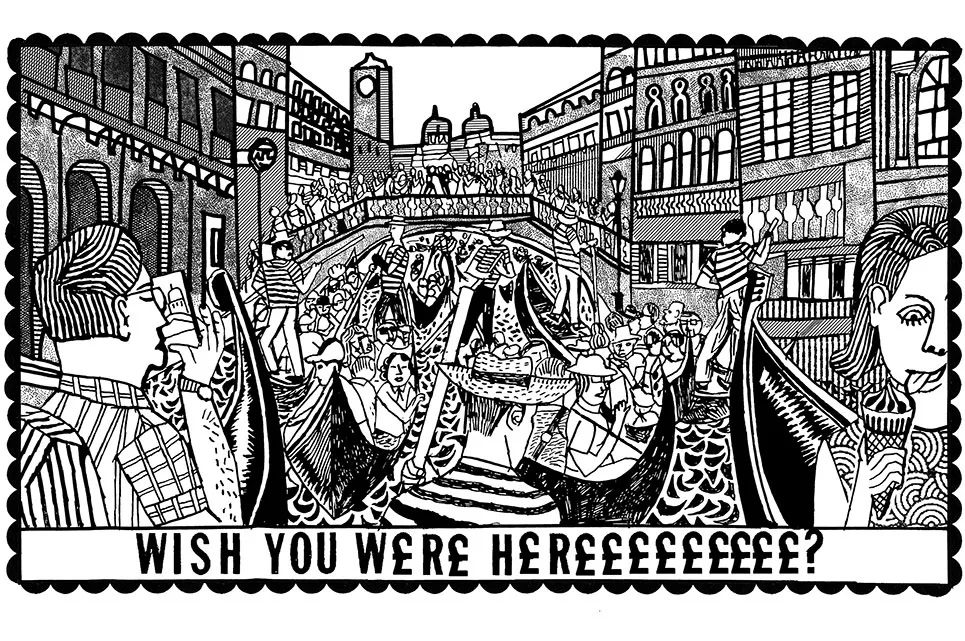

And the Indians, like the Chinese before them (and the Brits, Germans, Japanese and Americans before them) all want to go to the same places. No one is buying a bus tour of Dundee. Hardly anyone wants to visit Dakar, Detroit or Düsseldorf. Instead they all want to see London and Paris, Tuscany and Switzerland, the Louvre, the Prado and the Vatican. These places can take only so many tourists before they collapse under the weight of numbers (perhaps literally, in a place like Venice, where cruise boats further erode the Pearl of the Adriatic).

What then, will be done? What already happens in the exquisite Asian nation of Bhutan will happen everywhere. In Bhutan, tourist numbers are severely limited by a hefty daily fee (as I write, that’s $100). In other words, you have to pay a large sum simply to be in Bhutan, and you pay it every day you are there. This impost is highly effective — if you can afford it and if you are Bhutanese. It means Bhutan is devoid of those onerous crowds that otherwise send the locals insane.

Already the Bhutanese policy is being tried in Venice. As anyone who has been to Venice in July or August will know, the city at that time is often insufferable. Arriving here in high summer is like accidentally getting on the Central line at rush hour: it’s painful, sometimes horrifying and all you want to do is get out at Queensway.

The inevitable has happened. The Venetians have started charging day trippers a fee simply to visit the city. The daily price is at present set at five euros but I am sure this will rise, because so far it has not subdued the crowds. Personally, I reckon it will end up nearer to fifty euros: people are so desperate to see Venice it will take a serious case of sticker-shock to make them think twice.

It would be nice if the world was so altruistically organized that this tourist rationing was done by lottery (“Hooray, I’ve got tickets to go to Siena!”), but human nature being what it is, this rationing will be done with money (“My god, it’s £200 just to get into Siena”). Money makes more sense, above and beyond mere greed, because it means you can recompense local businesses that lose passing trade.

This means that in future travel to more enticing locales will become the province of the wealthy, as it was in the past. Visiting Florence in August will be like getting tickets for match day at the Emirates. A day trip to the Dolomites will be like front-row seats for Don Giovanni at the Scala. We might even see the rise of travel touts (“Psst, wanna buy tickets for Rome? — you get within six feet of the Trevi fountain”).

In which case, as a travel writer, the best advice I can offer Spectator readers is this: make the most of free travel while you can. And after that, there’s always Düsseldorf.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply