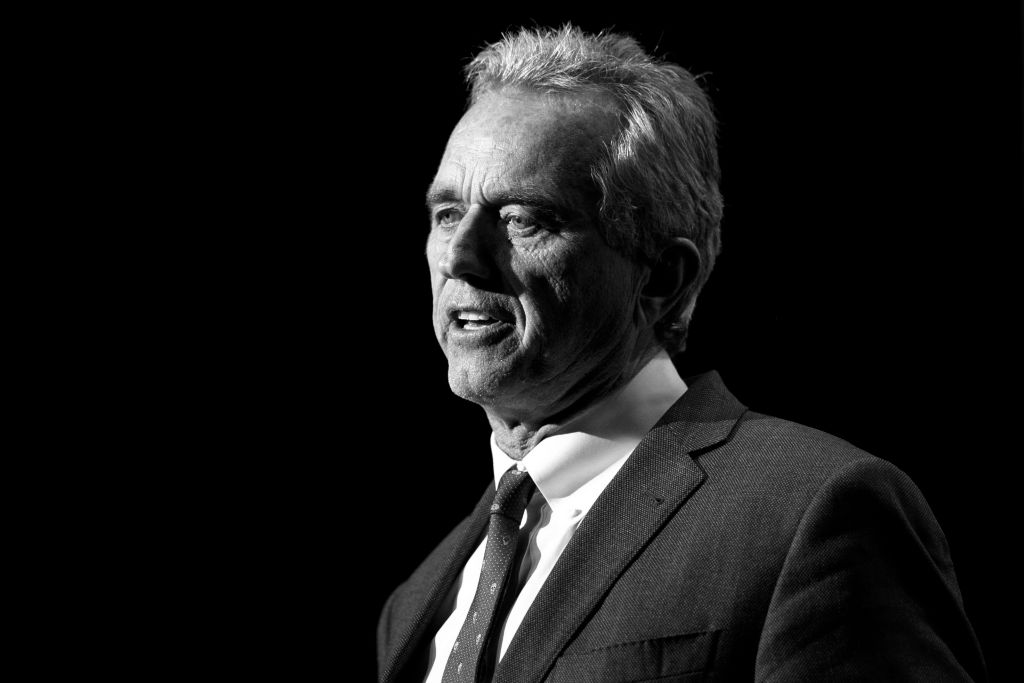

After Linda Como, a sixty-four-year-old administrative assistant from Quincy, Massachusetts, was fired from her hospital job for refusing to be vaccinated against Covid, she discovered Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s anti-vaccine activism, and it resonated with her. But that’s not the only reason Como came to the Boston Park Plaza hotel one morning in April to see Kennedy launch his long-shot 2024 presidential campaign.

“I grew up in Boston, went to Boston public schools, so you know the Kennedy family,” Como told me. “They’re like the royal family. So I’ve always been a fan of the Kennedys.”

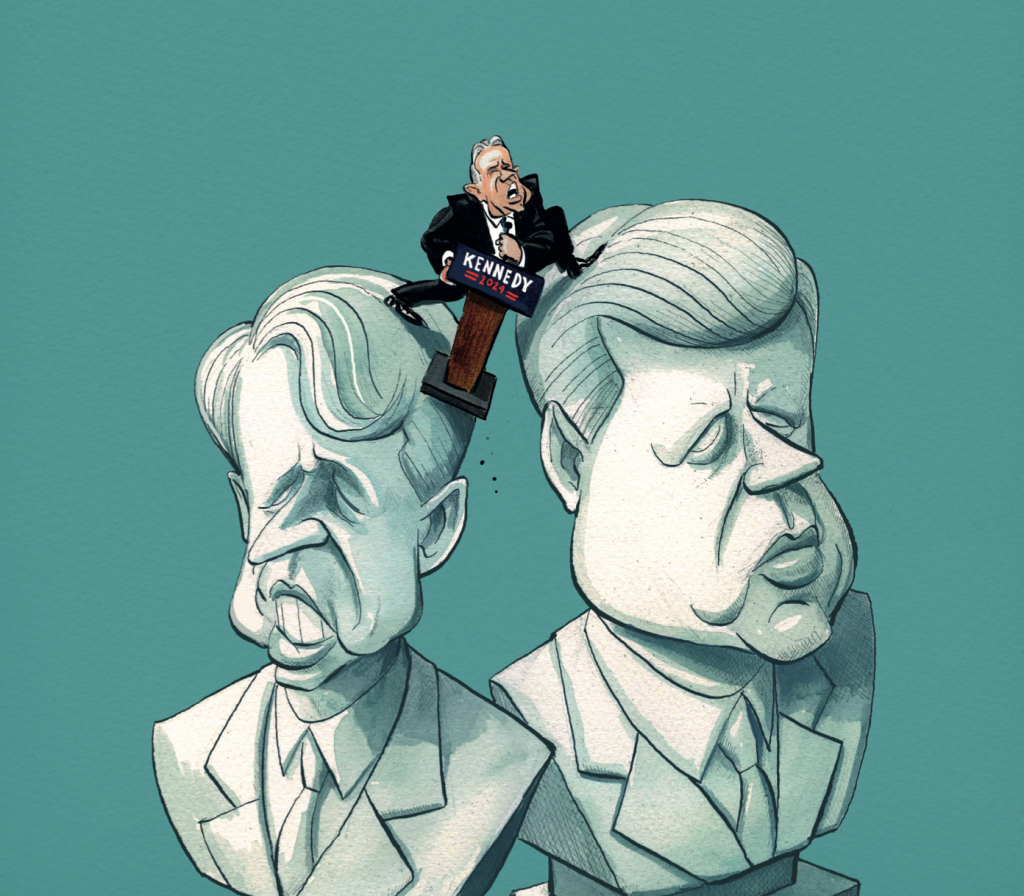

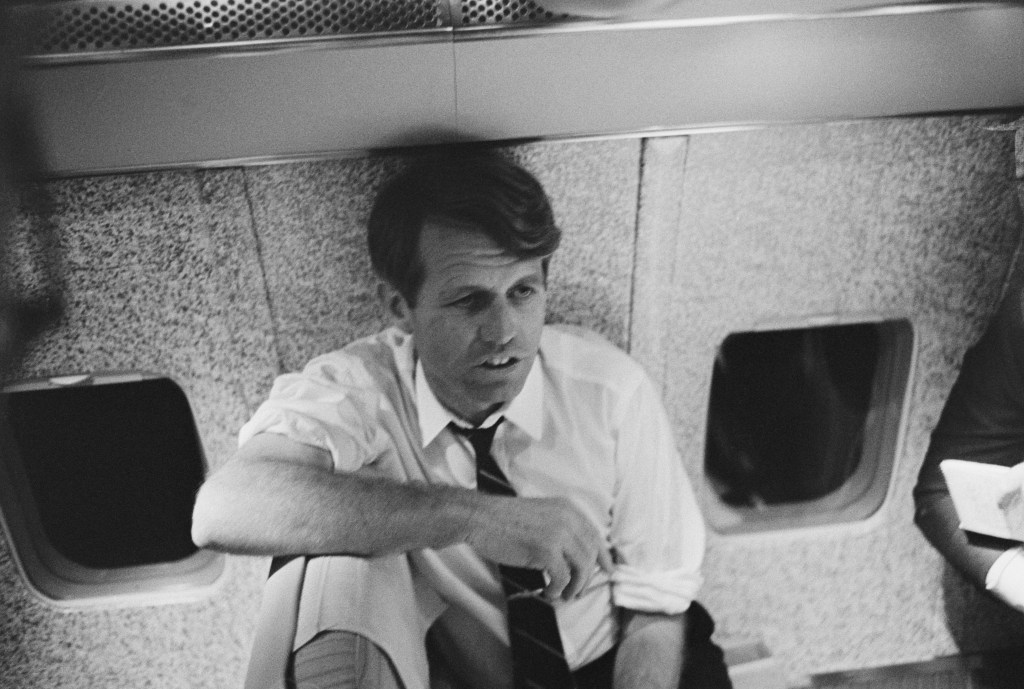

Kennedy lore runs deep in Boston. This is where Robert Kennedy’s father Robert F. Kennedy and his uncles John F. Kennedy and Edward M. Kennedy launched their careers; where the family patriarch, Joseph P. Kennedy, made the fortune that financed the family’s political ambitions. And it’s where RFK’s third child became the first Kennedy to run for president since his uncle Ted in 1980.

I arrived at the Park Plaza two hours ahead of time and found a long line of people waiting to get in. Though the New York Post later reported the presence of a significant number of “hot MILFs,” I didn’t notice them. Instead, the crowd seemed to skew older and a bit crunchy — a lot of New England boomers in sensible shoes. The event’s staging, on the other hand, was modern and slick. Screens set up next to the stage and in the overflow room showed a series of family photos — tanned Kennedys in boat shoes on the water, etc. A brass ensemble played a version of the Dropkick Murphys’ “I’m Shipping Up to Boston.” The merch tables were laden with signs and bumper stickers saying, “I’m a Kennedy Democrat” and “Heal the Divide.”

Kennedy’s wife, the actress Cheryl Hines, gave a very brief introduction. Hines plays Larry David’s wife on Curb Your Enthusiasm; her husband’s views have sometimes put her in an awkward position — when he compared vaccine mandates last year to Anne Frank’s ordeal during World War Two, Hines criticized him publicly, calling his comment “reprehensible.” But on the day of the launch, Hines looked every inch the supportive political wife as she took the stage in a turquoise sheath dress, though she spoke briefly, saying merely that her husband would soon “come out and make a very important announcement.” She introduced former Ohio congressman and leftist stalwart Dennis Kucinich. Kucinich is running the campaign, and his wife Elizabeth is also involved.

The entrance of Kucinich brought the house down; this was the biggest political name present. He compared Kennedy to Revolutionary War hero Paul Revere, “moving from town to town, warning us if water is unsafe to drink, warning us if our air is unsafe to breathe, warning us when our food is unsafe to eat, and warning us when pharmaceuticals are unsafe to use.” The launch came the day after the anniversary of Revere’s midnight ride; in his speech Kennedy tied the American rebels’ cause to his own: “The spear-tip of that rebellion was a fury that the colonists had against the merger, the corrupt merger, of state and corporate power.”

The older generation of Kennedys, or their speechwriters, had a knack for language. John F. Kennedy: “Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country.” Robert F. Kennedy: “Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.” Ted Kennedy: “For all those whose cares have been our concern, the work goes on, the cause endures, the hope still lives, and the dream shall never die.” This gift may have skipped a generation.

RFK Jr. spoke for nearly two hours, with no teleprompters, not appearing to read from notes, either. He segued from vaccines to lockdowns to the environment to the media to the war in Ukraine, croaking the words in his unusually strangled voice (the result of spasmodic dysphonia, a neurological disorder). He told the audience in great detail about lawsuits he worked on during his lawyer days, and shared his perception that no one his age has “full-blown” autism. After forty-eight minutes, he promised “I’m about halfway done with this speech. This is what happens when you censor somebody for eighteen years. I’ve got a lot to talk about.”

Kennedy had a successful career as an environmental lawyer, bringing high-profile suits against corporate polluters. But he is more widely known now as a critic of Big Pharma and, in particular, vaccination. He wrote in 2005 that he had been approached by parents who believed vaccines had caused their children’s autism, and began looking into it. At that time, the contemporary anti-vaccine movement was in its infancy. A British doctor, Andrew Wakefield, published a 1998 paper that posited a link between the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine and autism in children. The study had significant flaws: a tiny sample size of twelve subjects, no control group, and the fact that Wakefield had been hired to do the research by a lawyer for parents of autistic children who were seeking to sue drug companies. No credible link between the MMR vaccine and autism has ever been established and the Lancet retracted Wakefield’s paper in 2010. At the time Kennedy says he was approached, the battle lines hadn’t been as sharply drawn as they are today; in 2005 both Rolling Stone and Salon published a multi-thousand word essay he wrote condemning a kind of mercury used in vaccines as a preservative. In 2011 Kennedy founded the nonprofit World Mercury Project (now Children’s Health Defense) that became an important node in the anti-vaccine movement.

But his anti-vaccine activism didn’t become the next great mainstream liberal cause in the vein of his environmental work. Instead, the tone and content of Kennedy’s activism marginalized him in mainstream circles, where he has for years been considered a conspiracy theorist, particularly in the wake of Covid.

“Some look for scapegoats, others look for conspiracies, but this much is clear; violence breeds violence, repression brings retaliation, and only a cleaning of our whole society can remove this sickness from our soul,” RFK Sr. said in a famous speech after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. “For there is another kind of violence, slower but just as deadly, destructive as the shot or the bomb in the night. This is the violence of institutions; indifference and inaction and slow decay.” RFK Jr. clearly believes he is carrying on his father’s legacy of opposing institutional wrongdoing. But there is a fundamental difference between him and the previous generation of Kennedys. Despite their individual scandals and tragedies, they were all about possibility and hope, or at least the appearance of it. This was the family of Camelot, the moonshot project, the dream that would never die. They channeled the hopes and fears of a confident, if turbulent, postwar America, that believed things were getting better.

RFK Jr.’s message is that things are getting worse. Where the previous Kennedys typified the go get ’em ethos of the television age, RFK Jr.’s message evinces the pessimism and paranoia of the digital one. Here is the Kennedy our era deserves. His vision is ultimately a negative one, of a society on the brink of total capture by nefarious actors. And it reflects the mood of an increasingly vocal number of Americans who have lost faith in institutions and hope for the future. RFK Jr. probably can’t win. But his campaign could show how much that loss of faith, especially since Covid, has changed the political landscape.

I spoke to Kennedy on the phone the week after the launch. First I had texted Kucinich, to see if he could help arrange the interview. Then I texted Kennedy, who responded almost immediately: “You can call now.” At that moment, Kucinich called me and explained that he would recommend I be given the interview. He would coordinate with the press team and make sure everyone was across this. He did not know that the candidate had already decided to grant it, but I appreciated his enthusiasm. (Then I saw that Kucinich had texted me a presumably accidental pocket-recorded audio clip of a woman saying to him “I don’t think she’s friendly.”) Kennedy was between obligations, heading to New Hampshire the next day to meet union leaders and give a talk about Covid vaccine mandates at Dartmouth, and was multitasking by eating lunch at the same time he spoke to me. His lunch was avocado salad, white bean soup and risotto with clams. I asked him about the process of writing his speech. “I never wrote it,” Kennedy said. “I just said it.” Did he sketch out the structure, at least? “I did the structure in my head,” he said. “And then I just started talking.”

It would be logical for Kennedy to base his rationale for running on the uptick in anti-vaccine sentiment during the Covid years, but he downplayed this aspect. “I think most Americans are more interested in pocketbook issues and in freedom issues, and in restoring our democracy,” he said. “People in this country are desperate. They feel this system is rigged against them. I think they’re thinking more about, you know, just how to feed their families and make ends meet than they are about vaccines.”

But he does acknowledge, and embrace, the golden ticket of his Kennedy name. “I think that my family name is certainly a huge advantage,” he said. “Name-recognition is an advantage in any kind of democratic contest. And my name is one of the most recognizable in modern political history.” According to a source who was on the call, a week before his launch Kennedy debated with his team whether to use his nickname “Bobby” for campaign purposes, fearing that it would look too much like he was riding his father’s coattails or that the name itself was too juvenile-sounding. “When someone showcased proposed campaign materials employing the name ‘Bobby,’ I explained that I’ve always asked people to introduce me as ‘Robert’ in formal or official settings — as did my father,” Kennedy said in a text message. “Otherwise, I don’t care what people call me — not even ‘antivax.’”

Either way, Kennedy nostalgia is a factor. “I loved his father. I’m old enough to have loved his father. I was fifteen years old when he was killed,” said Tricia Santi, who is sixty-nine, the same age as the candidate. Santi drove down from Maine for Kennedy’s Boston rally. “And just to see another Kennedy come forward at this time and do this is amazing to see.” Santi is a “holistic healer” and has followed Kennedy’s work for years.

“All these people were alive when John Kennedy was assassinated,” said Santi’s husband Aram Aslanian, seventy, gesturing around at the other attendees waiting to get in the hall. “I was fifteen years old when Bobby was killed. What happened was, the country stopped telling the truth. They started lying after they killed the president. The CIA, the FBI — they killed the president. But nobody wants to talk about what happened as a culture. Our culture began to keep secrets.” RFK Jr.’s campaign, he said, is “a chance for Americans to swing back and tell the truth.”

The Kennedy brand name is still strong enough to attract some voters who don’t share Kennedy’s views. Joseph Pereira, fifty-eight, a businessman from Fall River, Massachusetts, was at the rally wearing a Kennedy for President pin he made himself. He got the Covid vaccine and doesn’t agree with Kennedy’s position on vaccines. His family has always held the Kennedys “in high esteem,” he said, because JFK signed a bill that enabled them to immigrate to the US from Portugal. Pereira worked on Ted Kennedy’s campaigns. And he’s now a fan of Robert Jr. Biden and Trump are “too old,” he said. “Bobby’s sixty-nine. I think he’s going to bring a new approach to politics. And I think that’s what we need. We need people who are bold enough to question authority.”

“I think if you weigh everything, all of the issues, I think the vaccines are not going to make that much of a difference,” Pereira said.

Early polls have shown RFK Jr. attracting as much as 21 percent of Democratic primary voters. But it’s uncertain how much that support owes to his name ID and voters’ lukewarm feelings about Biden, and how much those voters know about Kennedy otherwise. Moderate Democrats with fond memories of his father and uncles might not appreciate his frequent outreach to the populist right, which has embraced him as a fellow traveler during the Covid era.

Just a few days before his launch, for example, Kennedy spoke at Hillsdale College, an epicenter of Trump-era conservative intellectualism. Former Trump strategist Steve Bannon has sung Kennedy’s praises on his War Room show, and floated the idea that Trump should choose him as his running mate. CBS reported recently that Bannon had encouraged Kennedy to run, a claim Kennedy denies. “I’ve never talked to him about running,” he said, saying that other than appearing on his show a couple of times, he has only met Bannon once in person. This was when Kennedy was invited to take part in a “vaccine safety” panel Trump convened at Trump Tower during the transition after the 2016 election. But Kennedy is perfectly comfortable with speaking to the right, and sees it as a bonus. He was good friends with Roger Ailes, who hired him to host a long-forgotten wildlife documentary the pair shot in Kenya in the 1970s. Kennedy appears on Fox News regularly, including on Tucker Carlson’s show the week before Carlson’s surprise firing. “Some people criticize me, but how are we going to convince people if we don’t talk to them?” he told me. “The most important people who you can talk to are people who you don’t agree with.”

In framing this as a reaching-across-the-aisle exercise, Kennedy was evoking the legacy of his family elders, particularly his uncle Ted. “He would bring Orrin Hatch and John Kasich to our homes on weekends as these were some of his closest friends, and they were people who were absolutely antithetical to him and all of their political ideologies,” Kennedy said. “And he was able to do that — he was able to be so effective as senator — because he was able to make that distinction between politics and ideology. He never compromised his values. But he recognized that you had a lot of common values with people who are in the other party.”

But Ted Kennedy wasn’t going on red-pilled MAGA livestreams; he was hammering out legislative deals. The younger Kennedy says there is no deeper meaning behind his frequent appearances in conservative media. It’s because “the liberal media won’t let me on to talk,” he said. “I’m censored in the liberal media.” Running for president, though, has changed this; he said he had hundreds of media requests since his announcement, and was planning to go on Good Morning America and CNN. Kennedy subscribes to a Chomskyan view of the media as a top-down machine controlled by powerful interests, and though he reads widely, he doesn’t trust a lot of what he reads. “I would trust the New York Times about not anything to do with war or with the intelligence agencies or with pharmaceutical drugs,” he said. (That takes out quite a bit of the paper’s coverage.)

He doesn’t trust a lot in general. Kennedy is often described in the press as an anti-vaccine conspiracy theorist, and of course he rejects this as a smear. “The term ‘misinformation’ is just a euphemism for any statement that departs from government orthodoxies,” he said. But he does literally believe in conspiracy explanations for important events, including the assassination of his father in 1968. Kennedy doesn’t believe that the man convicted of the crime, Sirhan Sirhan, actually did it, and has called for Sirhan’s release from prison. He told Tablet recently that he believes the culprit was a security guard assigned to RFK the day before the shooting, in a CIA plot triggered by his father’s desire to re-open the Warren Commission investigation of JFK’s assassination.

Robert Kennedy Jr. was fourteen years old when his father died. His father’s entrance into the campaign had helped push the incumbent, Lyndon B. Johnson, out of the race. RFK had built an antiwar, pro-civil rights coalition and won the crucial California primary the day of his death. In his kickoff speech, the younger Kennedy explicitly compared his situation to his father’s: an upstart candidate taking on a calcified sitting president and building a coalition.

Kennedy told me that when he was deciding whether to run, his children worried that it would threaten his safety. “There are things that are worse to me than death,” he said. “And principally to me that would be that they were going to grow up in a nation that was diminished, that didn’t have constitutional rights, a country that they didn’t feel as proud of as the country I grew up in.”

Other than three of Kennedy’s six children and Hines, the Kennedy quotient at the campaign launch was low. Some of his siblings have publicly distanced themselves from Kennedy’s activism, though he said this hasn’t affected their personal relationships. It’s unclear to what extent Hines will continue to be involved. “I hope” she will, Kennedy told me. “She’s a huge asset for me.”

This isn’t an ideal time to launch a Democratic primary campaign. President Biden announced his re-election campaign in April, and since he’s running for re-election the party probably won’t hold primary debates, a potentially crucial venue for dark horse candidates like Kennedy or Marianne Williamson to raise their profiles. It also limits the number of available staff willing to work on an outsider campaign.

Kennedy’s supporters are filling the gap in various ways. His campaign team is made up mostly of friends and allies from the anti-vaccine movement. Kennedy told me the campaign’s resources were being “crowdsourced,” but it may be difficult. A source with direct knowledge of the campaign told me that the campaign has had trouble renting email lists to use for fundraising, either from the right or the left, and is relying on its own list of 20,000 names. Contrast this with the legendary 2.5 million-strong Bernie Sanders email list. (Asked about the email fundraising, Kucinich said “our internal discussions have been the opposite” and called the lists I was referring to “stale.”) It complicates matters that the campaign’s natural demographic is “the crunchy crew in the antivax and medical-freedom movement that I think is hard to pigeonhole in political lines. I don’t think they’re motivated by partisanship,” this source said. “They’re trying to reach that demographic, but there’s not an obvious way to talk to them.”

There is already a super PAC promoting Kennedy’s candidacy. Called American Values 2024 after the title of Kennedy’s 2018 memoir, it took out a full-page ad in the Boston Globe to promote the Boston kickoff event. It’s being run by John Gilmore, who left his role leading the New York chapter of Children’s Health Defense to found the committee. Gilmore believes that the anti-vaccine movement (he prefers the term “vaccine safety”) has grown strong enough in the wake of Covid to power a political movement.

“Our movement as a result of Covid has become enormously larger than it used to be,” he said, estimating that it was “orders of magnitude bigger” now than it was twenty years ago when you could “sort of cram the whole movement into a van.” The growth of Children’s Health Defense is one example; the AP reported in 2021 that the charity doubled its revenue in 2020.

“It’s an issue that can and has decided elections and probably will be a major factor in the presidential election, and it hasn’t been up to this point,” Gilmore said.

Kennedy’s biggest opportunity is likely to be in free-thinking New Hampshire, traditionally the first primary state on the calendar and one that has energized anti-establishment campaigns like Ron Paul’s in 2012. Biden’s push to get South Carolina to hold the first primary next year could mean he’s not on the ballot in New Hampshire if it goes first anyway, which it will do unless its legislature changes a relevant law by June this year. This wouldn’t be enough to really interfere with Biden’s path to the nomination, but it would draw attention to Kennedy and thus to a messenger — and movement — that Democrats would rather not highlight. Kennedy insists, though, that his is no protest campaign. “I’m in it to win it,” he said. “I’m not thinking of Plan B.”

This article is taken from The Spectator’s June 2023 World edition.