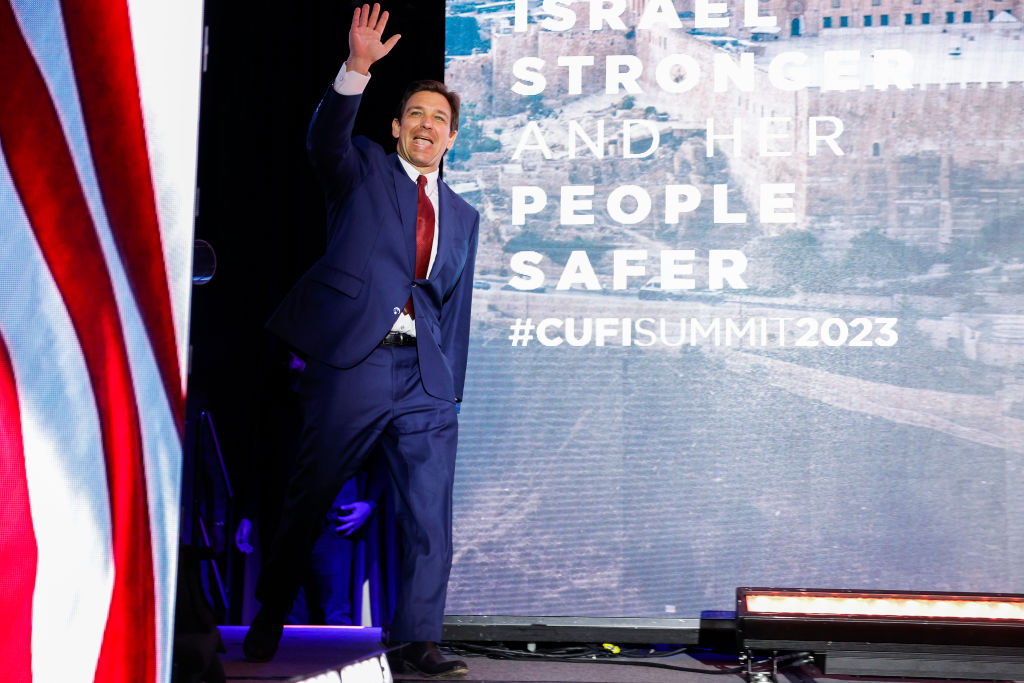

What if the problem for Ron DeSantis isn’t that he resembles the spiraling candidacies of the past, but that he’s emulating someone who had a great start, then turned a plateau into a cascade?

The general experience in Republican presidential flameouts over the past decade and a half has been the very obvious crash and burn. We have Rudy Giuliani in 2008, who botched his Houston abortion speech then said he would wait until Florida and dropped from a 44 percent lead into utter ignominy. We have 2012’s Rick Perry, who surged to a 29 percent lead over Mitt Romney’s 17 percent in the summer of 2011, only to drop out in the same place he announced, South Carolina. And in 2016 we have more than one example, but the most prominent being Scott Walker, whose double-digit lead evaporated in the space of weeks after two lackluster debate performances.

For some reason, American voters really, really care about debates, which resemble in no way anything that candidates have to do as president. This is because American voters are programmed by the media to think these media-constructed and media-focused events matter a great deal more than they actually do. A better proof of management capability would be running a Dairy Queen for a weekend. But that’s not as entertaining, so instead we judge our future commanders-in-chief based on the equivalent of a Cards Against Humanity question.

The DeSantis campaign is struggling, everyone will tell you, despite the fact that he’s raised more money than pretty much everyone and seems to be solidly in second place in the early states, unless you put your faith in weird online-only polls not known for their accuracy in Iowa or New Hampshire. But there’s a definite quality to this campaign that seems, how shall we say it, flustered? Confused? Disoriented? And in a specific way that might remind you of another recent campaign with high expectations that got off track early.

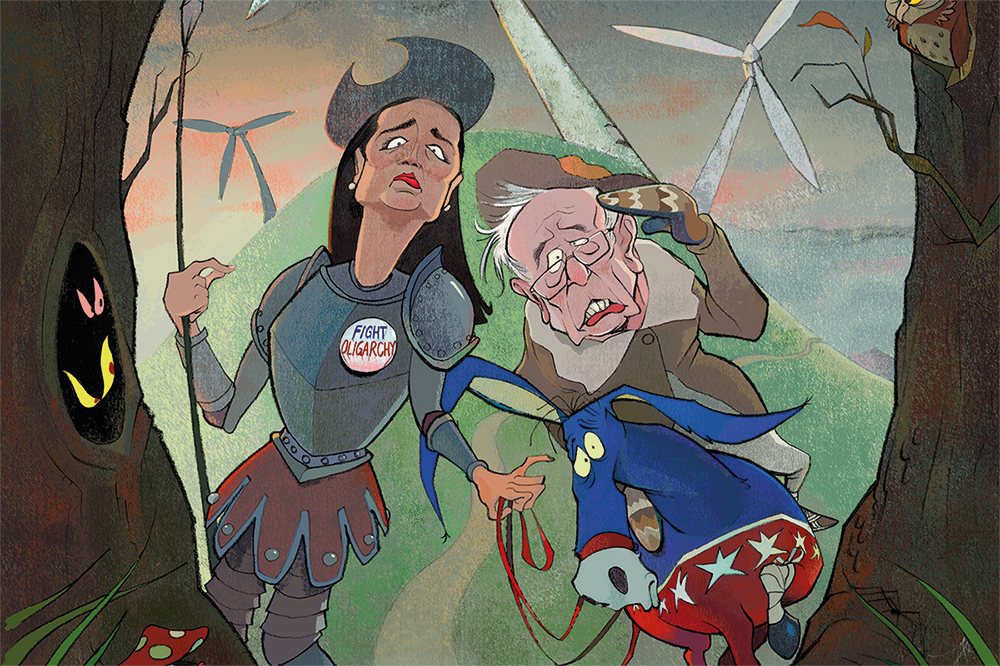

Consider the 2020 campaign of one Kamala Harris, rising star, great speechmaker, looked up to by everyone, touted as the female Obama for years. And then she got into the race, and what happened? After a sparkling launch, she dropped out earlier than anyone expected — and the New York Times explained why:

One advisor said the fixation that some younger staffers have with liberals on Twitter distorted their view of what issues and moments truly mattered, joking that it was not President Trump’s account that should be taken offline, as Ms. Harris has urged, but rather those of their own trigger-happy communications team.

The piece, written in November 2019 — a month before Harris would drop out — included this description of an attempt at a pivot:

Ms. Harris is now attempting a pivot, taking a less scripted approach to campaigning. On a conference call with donors after the last debate in mid-November, Jim Margolis, a senior campaign advisor, pointed to her improved performance as a case study in letting “Kamala be Kamala,” according to one person who participated in the call — a reference to Ms. Harris’s strengths when she is listening to her competitors’ comments and reacting freely.

Oh. Oh no.

“DeSantis camp briefs donors, pledges to ‘Let Ron be Ron’”

Part of the Let X be X framing of things is valid — where a candidate has been put inside guardrails and prevented from being themselves. This worked as recently as 2008, where John McCain’s campaign for the nomination blew up early, and he was forced back into an insurgent posture. But that approach is rarely successful, and marked more by risk than results.

For DeSantis, the problems are clear. Loyalty to Donald Trump is still strong among half of Republicans, even with DeSantis’s pointed critiques of his policies. The presence of multiple South Carolina candidates in the race hampers his potential momentum even if he wins Iowa, which seems to be the singular focus of his effort. And just as Harris’s team suffered from an extremely online tenor to her campaign, DeSantis’s team seems more interested in meme videos, Twitter scraps and the internet field of conflict than the on-the-ground demands of winning.

Perhaps that won’t be determinative this time around. But if it is, DeSantis could well end up in the Kamala category — someone who lost track of the demands of winning because there were so many things to respond to every day. As two of the most prominent Gen X politicians, a DeSantis decline would be an indictment of the generational vulnerability to the virality of distraction. They could focus on winning, but they’d rather not.