I found Jean-Pierre standing at a half-open window gulping down lungfuls of stale Dutch air as our night train chuntered, unseeing, through an expectoration of towns: Zutphen, Eefde, Gorssel. He was seventy-nine years old, he told me, and returning to Berlin for the first time in sixty-one years for a meeting with an old friend.

Back in 1962, Jean-Pierre had been a very young Belgian Jesuit employed in smuggling hard currency from West to East Berlin, which he did by stuffing the notes inside a plaster cast which covered his right leg. There was nothing wrong with his leg, of course. His contact in an illegal Christian charity in the East was a man of the same age, called Norbert — and it was this chap he was going to see for the first time in almost six decades.

They had lost touch with one another in the mid-1960s, but Jean-Pierre had embarked upon a kind of demented scouring of social media sites recently and found, to his delight, that his former comrade was alive. His excitement was palpable and touching; he had scarcely believed that such a reunion could be possible. I asked him if Norbert was happy in the new(ish) Germany. He told me that his old friend was a little ambivalent. “He said that in the old days we had no money, but we understood what was important in life. For many, that understanding has now gone. But… they are rich.”

By an uncanny coincidence, the carriage in which we were traveling first saw service in 1962. Really. This was part of the much-heralded new European sleeper service from Brussels to Berlin which began running in May this year. The carriage had no electricity, no outlets, no buffet car and the toilets were a noisome foretaste of hell. The journey is also extortionately expensive: one berth on this lumbering, filthy behemoth cost the same as all three tickets for my family to sleep blissfully on the modern, spotless, well-equipped night train from Prague to Poprad in Slovakia, with a toilet and shower in every room.

But then trains in western Europe are not faring too well generally, especially German trains. You think we have it bad in the UK? According to Network Rail, the proportion of British trains arriving within five minutes of the scheduled arrival time is 92.4 percent. For Deutsche Bahn, the figure is 65.2 percent (and that’s for within six minutes). Lars, a businessman visiting his father in Berlin, told me his train from Frankfurt had been delayed by five hours, with no explanation given.

Our train steward was an odious bullet-headed Prussian who made it absolutely clear he couldn’t give a stuff that one coach was out of service and the passengers thus marooned, or that there was no buffet car. Nothing to do with me, he barked, with a Waffenish satisfaction.

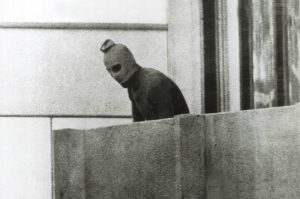

Berlin may be the only city in the world whose entire tourist industry is predicated upon repentance. The Wall, the DDR, the Stasi, the Holocaust — Es tut uns sehr leid (We are very sorry). I first saw Berlin in 1986 when I traveled from London to Moscow in a tour organized by the Communist Party of Great Britain (Marxist-Leninist). Bus to West Berlin, U-Bahn to East Berlin, train for three days to Moscow. It was chaotic and led by an idiot. In East Berlin he revealed that he had forgotten to purchase any Ostmarks for the U-Bahn tickets: “But we are socialists and they are socialists, so we shall just get on without paying and it will be fine.” A little later, as we were lined up against the wall by angry policemen with guns, the idiot pushed me forward to explain the situation, as I was the only traveler with a smattering of German. It was not my finest moment. In the panic I forgot the German for tour leader was Reiseleiter and announced with great conviction to the most belligerent copper: “Ich bin der Gruppenfuhrer!” Really, really not amused.

In Slovakia we stayed at the beautiful Habsburg-era Grand Hotel in Stary Smokovec, at the foot of the Tatra mountains. Its heyday was prewar, before the Germans ransacked it and the commies made it a retreat for Great Socialist Statesmen, such as Leonid Brezhnev, Harold Wilson and Fidel Castro (who played ping pong with the staff). It still has its magnificent grandeur and a room is about a fifth of what you’d pay in Berlin or London. Eighty-odd miles to the east a country is at war — and the Slovaks are more equivocal about who to support than their Polish and Czech neighbors. About half the country thinks Vladimir Putin was right to invade and blames NATO. Is this a consequence of that complex hierarchy of national hatreds in central Europe, with the Slovaks siding, puzzlingly, with their most vexatious neighbors, Hungary? (A Hungarian diplomat once told me a joke: “What do you call a Pole who wishes he was Hungarian? A Slovak.”) They go to the polls soon and way out in front is the Russophile, deeply socially conservative, anti-immigration, Euroskeptic former prime minister Robert Fico. Lovely Slovakia, like most of the rest of Europe, is now tilting steeply to the right.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2023 World edition.