Last September, when 60 Minutes asked Joe Biden what he thought of the August raid at Mar-a-Lago where the FBI found folders of classified documents mixed in with Donald Trump’s personal effects and papers, the president said he was shocked. Biden wanted to know how “anyone could be that irresponsible.” He worried about what sources and methods might have been compromised by his predecessor’s carelessness. Were there agent lists among those purloined records?

That bit of political point-scoring has become a petard with which the president has hoist himself. Two months later, Biden’s lawyers found classified documents in his Wilmington home and garage and in his personal office at the Penn Biden Center in Washington. Confronted in January about his own carelessness, Biden shrugged it off. The garage which houses his vintage Corvette Stingray, he assured reporters, was locked. “So it’s not like they’re sitting out in the street.”

As if that turnabout weren’t enough, enter Mike Pence. When he was asked in January about Biden’s mishandling of documents, Trump’s vice president said it was a “serious matter.” Wait a couple of weeks, and what do you know? Pence’s lawyers too found classified material in his Indiana home.

There is an obvious point here about the equal treatment of goose and gander. After the FBI raid at Mar-a-Lago, Washington treated the matter as a five-alarm scandal. So why should Biden’s or Pence’s carelessness with state secrets not also fuel the outrage machine?

Here it’s worth distinguishing between a well-deserved tu quoque at the expense of one’s political rivals and a defense of the US government’s dysfunctional system of state secrecy, a far more serious matter than political score-settling. Because in Washington, the mishandling of classified documents is a bit like gambling at Casablanca: a ubiquitous offense that is almost always overlooked until it isn’t. Analysts take home documents from the office. Senior officials leak intelligence assessments to reporters. Members of Congress discuss classified briefings with their staff and colleagues. In this sense, the country’s secrets are treated like gossip, tidbits whispered over drinks after hours.

At the root of this problem is the phenomenon of overclassification — the national security state has long created far more secrets than it could reasonably be expected to protect, and to this day it lacks an agreed-upon, efficient means of declassification. When the FBI was investigating whether classified material had found its way onto Hillary Clinton’s private email server in 2016, another 60 Minutes interview famously featured then-president Barack Obama’s assessment that “There’s classified and then there’s classified.” Obama was publicly acknowledging a problem that Congress and the executive branch have quietly stipulated for decades. In 1998, senators Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Jesse Helms chaired a commission to examine excessive secrecy in the US government and concluded that the problem was endemic. Every few years, another bipartisan commission comes to a similar conclusion.

There are many reasons for overclassification. It happens all the time in war: knowing the exact time and location of troop movements is necessarily a state secret before a military operation, but once it’s over, there’s no reason for plans to remain secret. And sometimes analysis is classified because the higher the classification the more valuable it is perceived to be.

Occasionally the state makes something secret because if it were exposed it would prove embarrassing. That is what happened with a secret history of the Vietnam War commissioned in 1967 by then-defense secretary Robert McNamara. Four years later, an analyst named Daniel Ellsberg leaked these “Pentagon Papers” to the New York Times. The Nixon administration tried to prevent the Times from publishing excerpts of this secret history, only to lose the case 6-3 at the Supreme Court.

Writing in concurrence with the majority, Justice Hugo Black said that “only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government.” Other justices argued that while there may be circumstances where the government could appropriately prevent news outlets from publishing state secrets, the Nixon administration had failed to meet reasonable criteria for such prior restraint.

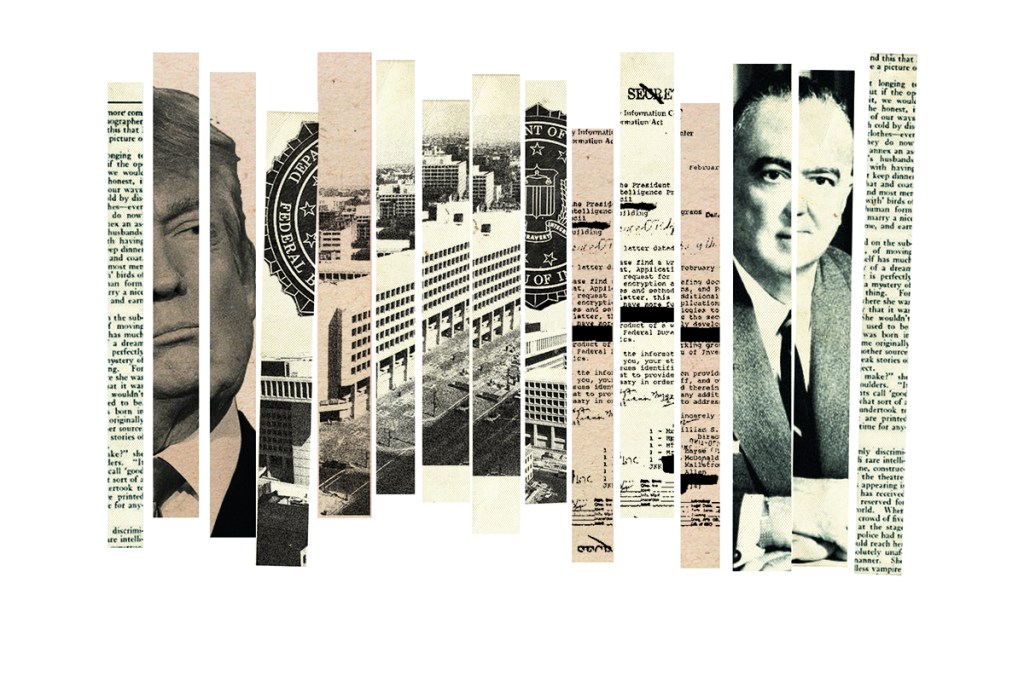

With the publication of the Pentagon Papers in 1971, the culture of the Washington press changed. After the Pentagon Papers and the Watergate scandal which was revealed beginning in 1972, major outlets no longer accorded the national security state the benefit of the doubt. The early 1970s in particular were boom years for the unmasking of America’s darkest secrets. In 1974 Seymour Hersh published stories in the New York Times on an internal CIA memo known as the “family jewels,” which documented a history of the agency’s domestic skulduggery and surveillance, in violation of its charter. In 1971 a group of peace activists broke into an FBI annex outside Philadelphia and stole reams of documents that eventually gave the press the first glimpse of the bureau’s surveillance of the anti-war and civil rights movements known as COINTELPRO.

Much of this new adversarial journalism really did expose official corruption and wrongdoing, leading to important reforms after Congress created permanent oversight committees to keep tabs on the intelligence community and the FBI. At the same time, though, this new approach to journalism could be abused. Over time, staff and spokesmen from the White House and other federal agencies began to anonymously plant selectively declassified information with journalists, for a variety of purposes. What began as leaks from whistleblowers ended up becoming another tactic in Washington’s power wars, a way to advance a favored policy or shift the blame for a fiasco.

In a sense none of this was fair to the FBI, the federal agency tasked with investigating classified leaks in a town full of leakers. At first the FBI was scared off surveilling and investigating the journalists who were leaked to, after the Nixon administration was vehemently criticized for using retired CIA and FBI officers to spy on the press and its other domestic critics.

After 9/11, though, the Department of Justice began to take prosecution of leakers more seriously. For example, in 2004 DoJ targeted two lobbyists for the American Israel Public Affairs Committee and a Pentagon analyst named Larry Franklin for mishandling classified material. The entire case was a clown show. Franklin had hoped to get the lobbyists to pass on an analysis of Iranian operations in Afghanistan to the president’s national security adviser. The case against the lobbyists was eventually dismissed, but Franklin took a plea deal after the government threatened to cut off his pension.

During the Obama administration, the FBI became even bolder. It began to eavesdrop on journalists in leak investigations, at one point collecting the metadata for phones from the Associated Press Washington bureau and placing a Fox News reporter under surveillance.

An enduring irony of the period is that the FBI itself was a dripping sieve of its own proprietary information: in 2018 Justice’s IG concluded that the bureau’s own rules prohibiting contact with reporters were widely ignored, and that dozens of FBI officials were in regular contact with the media.

The bureau has always leaked. J. Edgar Hoover ran an entire office of ghostwriters that corresponded with journalists who were led to believe they were being brought into the director’s inner circle. “Deep Throat,” the source for the Washington Post’s reporting on Watergate, turned out to have been FBI deputy director Mark Felt, who soured on Nixon when he wasn’t nominated to succeed Hoover. More recently, fired FBI director James Comey, through a cut-out, leaked his own personal notes of encounters with President Trump to the New York Times.

The stories that came out of Comey’s notes reveal an often-overlooked danger of Washington’s excessive secrecy: leaking classified information can mislead as much as it reveals. For example, the big headline from the Comey memos in 2017 was that President Trump had pressured his FBI director to “go easy” on Michael Flynn, Trump’s first national security advisor, who resigned after twenty-four days on the job.

Flynn left the White House in February 2017 after the Washington Post published an exposé based on highly classified FBI transcripts of his conversations with Russia’s ambassador to Washington during the transition period after the 2016 election. At the time, the Post reported that Flynn’s conversations could have been an “inappropriate and potentially illegal signal to the Kremlin that it could expect a reprieve from sanctions.”

What was missing from the Post’s reporting was that the lead agent investigating Flynn had recommended that the case against him be closed. The agents who interviewed him under false pretenses themselves did not conclude he had lied to them when they asked him about his contacts with the ambassador, assessing that Flynn had misremembered the call. Finally, in 2020 the Trump administration declassified the actual transcript of Flynn’s conversations. It showed that the incoming national security advisor was not implying that the new administration would relax sanctions but urging the Russians not to escalate in their response to Obama’s previous expulsion of Russian spies.

Comey’s leak made it appear that Trump was trying to obstruct a legitimate investigation of his former national security advisor. It took another three years for the full picture to emerge: the FBI had no reason to investigate Flynn by the time of Comey’s encounter with Trump.

Understanding this sort of impenetrable tangle offers important context for the current secrecy scandals in Washington. And the role of sheer bureaucratic inertia and red-tape snarl-ups shouldn’t be underestimated: at the end of January, Biden’s director of national intelligence Avril Haines informed the Senate Intelligence Committee that she could not show them the actual documents allegedly mishandled by the current and previous presidents. There are now two special counsels investigating these matters, she said, and sharing this information would hinder the probes.

Senators from both parties were justifiably furious. They should not, though, have been surprised. The national security state has protected too many secrets for too many years and no one has been able to stop it.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2023 World edition.