“If you’re having a bad day at work,” read the Twitter meme, “at least you’re not Harry Cole or James Heale.” The inglorious collapse of Liz Truss’s government put paid to many plans, but none more so than the biography of the lady herself, which Harry and I have been writing for the past ten weeks. Having started the project as her biographers, we ended it as her political obituarists, furiously rewriting copy as it became clear that our intended cliff-hanger could only have one ending.

Our deadline was October 29. Harry (who is the political editor of the Sun) and I signed the deal for Out of the Blue: The Astonishing Rise of Liz Truss on August 20, so we had less than two months to throw ourselves into the madcap world of Truss. Of course, we had no idea just how mad things were going to get.

We began by making trips to dusty archives in Oxford and the British Library, as well as local landmarks in Greenwich, where Truss has lived for twenty years. In various pubs around Westminster, we drank with many of her old friends, colleagues, rivals and her (dwindling) band of admirers, who shared their memories.

The impression we formed from these interviews is that Truss’s steady rise through Westminster had sometimes obscured her steely self-belief and her iconoclastic instincts. And while such traits have their merits, they could produce spectacular blow-ups. Truss’s failed childcare ratio reforms during her first ministerial job at education in 2012 (which is when Dominic Cummings gave her the nickname the “human hand grenade”) can now be seen as a foreshadow of her disastrous mini-Budget ten years later.

In early October, as Harry and I were approaching our deadline, the British government started to fall apart. We had a ringside seat as the bullish optimism of team Truss we had witnessed over the summer turned to despair.

Late on the first night of the Conservative Party Conference in Birmingham, I was sipping on a glass of warm white wine in a Tory grandee’s suite in the Hyatt hotel with a dozen other journalists and cabinet ministers when we heard a sudden commotion in the corridor outside. Harry was in a shouting match with a No. 10 advisor over the rumor that the government was flip-flopping on the 45p top rate of tax.

“We’re running the story unless you deny it!” demanded Harry. “I cannot confirm those reports,” insisted the aide robotically as the back-and-forth reached its climax. Suddenly, they raced each other to the elevator. “We’re running it!” shouted Harry, as the doors closed. The news broke on the Sun website and that’s how the world — and the ministers in that suite — learned that the Truss mini-Budget was beginning to unravel.

“Pure carnage,” is how one Truss insider describes the fifty-day regime as it sped through successive crises. But in retrospect, the calm before Truss took office is arguably more important than the chaos which quickly engulfed her premiership. For most of the three weeks before Truss won the summer’s leadership race, she had been holed up in Chevening, the palatial country house which serves as the foreign secretary’s official residence. By this point in the race, it was clear that Truss was going to win and she was finalizing her decisions about her cabinet and economic agenda.

It was here, isolated from many of her key advisors, surrounded almost entirely by civil servants and flushed with imminent victory, that she embarked on a course that would alienate her party, the markets and the electorate.

There was a positive atmosphere when Harry and I arrived to interview her two weeks before she walked into Downing Street. Skeptics on her team, concerned about the wisdom of such engagement, were won over by a peace offering of a crate of French rosé. Truss had agreed to talk about her early life, and for more than an hour she displayed the traits which her friends and confidantes had described to us: she had dry humor, brains and a quick wit. As with many politicians, a rolling camera has a transformative effect on her, bringing down the shutters on her personality. “It’s a bit like This Is Your Life,” she joked as we asked about dates, people and memories from her distant past that she had long forgotten: “You know more about this than me.”

Her team agreed to a follow-up interview at the same location shortly after she entered No. 10, since Chequers was undergoing renovations. Our abiding memory of that second session — held the weekend after the mini-Budget — was the unnerving calm of the prime minister even as the markets were in full panic mode. The plans for a third interview (on the subject of Truss’s leadership campaign, early days in No. 10 and abiding political philosophy) were canned as the demands of office became too much.

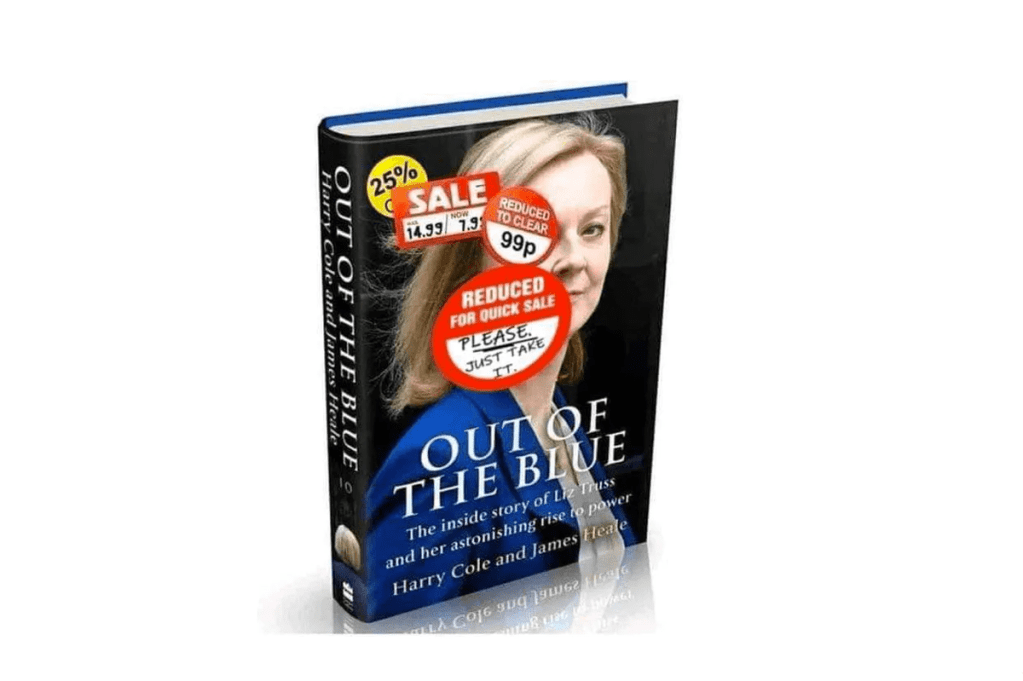

As her resignation became inevitable, our book became an online meme. Screenshots of the book with multiple “99p discount” stickers photoshopped on top of the cover were shared thousands of times. Through boomer WhatsApp groups, the meme reached my bemused father; my teenage sister was shown it by an excited student during her university freshers’ week. On Twitter, football fans joined in the fun, mocking up a lookalike book cover about Steven Gerrard’s unsuccessful stint as Aston Villa manager, titled Out of the Claret and Blue.

Influencers on the professional networking service LinkedIn have used our book as a source of “there but for the grace of God” inspiration: “Imagine investing time and money into a project that literarily [sic] ended even before you launched it,” wrote one aspiring American business guru to his followers. “So remember… If a prospect ghosted you, move on like Harry and James.”

On Facebook, the bookmaker Paddy Power’s official account, which has 1.5 million followers, shared a photoshopped image of hundreds of copies of our book being pulped. Its infamy grew and media requests from Canada, America, the Middle East and Europe flooded in. The German magazine Der Spiegel got in touch with me to ask how it felt to have “so many memes out there mocking the fact that your biography of Liz Truss is not due to be released for six more weeks.”

It was all quite surreal. Sir Keir Starmer even used the book as a punchline at Truss’s final Prime Minister’s Questions (pilfering a joke from Private Eye as he did so). “A book is being written about the prime minister’s time in office,’ he began. “Apparently it’s going to be out by Christmas. Is that the release date or the title?” As the MPs roared, my phone lit up. “You know you’re being rinsed in parliament?” In such circumstances, there was little else to do but laugh — and keep updating copy until the end.

As the government collapsed around us, we leant into the chaos. We had thought we might get two years of sales; instead, by late September, two months looked optimistic. We thought about changing the title. We joked that The Downing Street Weeks could have been a possible nod to Thatcher’s memoir, though Out of the Blue and Into the Red would better reflect the state of the nation’s finances. In the end we chose to keep the title but swapped the strapline instead. What was originally “The astonishing rise of Liz Truss” was euphemistically changed to “The explosive rise of Liz Truss” before eventually settling on “The unexpected rise and rapid fall of Liz Truss.”

Initially, we thought the book would end on that infamous party conference — Truss taking to the stage as her critics circled around her. There were, at the time, suggestions by some of her supporters that she could still turn things around. Those hopes vanished as soon as she fired Kwasi Kwarteng, her chancellor and closest ally. She had hoped to rule as a Tory radical but the reversal of her agenda and Kwarteng’s departure meant governing as a conventional Conservative — in the manner of Theresa May — was the only option left to her. And even that forlorn hope of mere survival barely lasted a week.

I asked one No. 10 advisor to summarize the failings of the administration. “Frankly it was hubris,” I was told: “hubris followed by nemesis.” Fortunately for Harry and me, nemesis is (yet) to follow our hubris in trying to write the life and times of a politician whose legacy was not yet known. Our book is finally finished. But after our troubles with Truss and the whirlwind of the past two weeks, don’t expect us to embark on another work on a living politician any time soon.

Note from the editors: Spare a thought for the less fortunate this Christmas. You can pre-order James Heale’s book here. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.