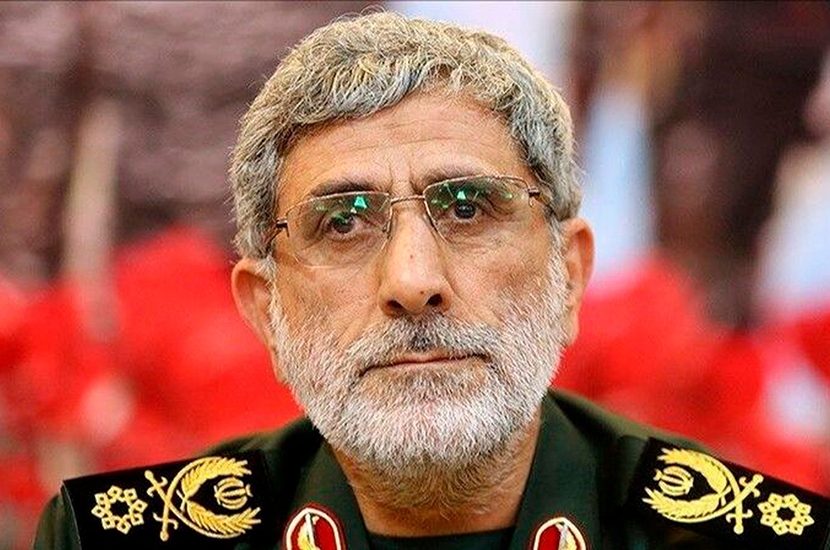

Iran’s new meddler-in-chief in Iraq is a bespectacled general called Esmail Ghaani. Brought in to replace Qasem Soleimani after his death in a US airstrike in January, he has the same green uniform as his predecessor, the same gray beard, and the same orders to make Iraq’s Shia militias do Tehran’s bidding.

That, though, is where the similarities end. Soleimani was a legend among his followers in Iraq — he spent years building contacts with local commanders and joined them on the battlefield against Isis in Mosul. Ghaani, by contrast, is an owlish, uncharismatic figure who looks like he might be happier behind a desk. Unlike Soleimani, he doesn’t speak Arabic and has to rely on a translator during his visits to Baghdad.

All of which helps explain why, six months after Donald Trump ordered Soleimani’s assassination, predictions that it would spark even worse bloodshed have largely failed to come true. Back then, it looked like the moment Trump’s critics had been waiting for — the act of recklessness that would set the Middle East ablaze.

So far, though, apart from an initial flurry of rocket attacks, not much has happened. There have been no terror ‘spectaculars’, no kidnappings of Americans on the streets of Baghdad or Beirut. And much of that, diplomats say, is because Soleimani has simply proved impossible to replace. After all, personal contacts and trust count for a lot in the Middle East, especially when you’re asking people to fight and maybe die for you.

Moreover, when Soleimani’s replacement goes to Baghdad these days, he’s kept under watch by a new Iraqi leader who is rather less welcoming. Mustafa al-Kadhimi, a former exile who used to live in London, was sworn in as Baghdad’s Prime Minister in May. Unlike previous Iraqi PMs of the post-Saddam era, who’ve been mostly in Iran’s pocket, he’s staunchly pro-western. He’s also youngish (53), smart and secular — in short, the sort of leader the West has long hoped for in Iraq.

Kadhimi’s very appointment was a sign of a growing anti-Iranian feeling in Iraqi politics. This began in the fall, when huge anti-government demonstrations swept the nation. While the demos were partly about lousy government services, they took an anti-Iranian turn when Iran-backed Shia militias got involved in suppressing them, killing hundreds. So when Kadhimi’s predecessor resigned in November, the pro-Tehran bloc in Iraq’s parliament realized that they couldn’t just put in another Iranian placeman as PM.

That didn’t stop Iran leaning on them to do just that. When General Ghaani first visited Baghdad in March, part of his brief was to whip the MPs into line, just as Soleimani would have done. Instead, Ghaani found several senior Shia leaders refusing to meet him. According to Al-Jazeera, the Iraqi government even made him apply for a visa, something Soleimani never had to bother with. As one western official told me: ‘Ghaani has struggled to fill Soleimani’s shoes, and has not had the same influence over the formation of the new government.’

So what do we know about the new PM? His résumé is a varied one. He was forced to leave Iraq in the 1980s for opposing Saddam, and spent many years working in London as a journalist and human rights activist, building an archive of Saddam’s crimes. For the past four years, he has headed Iraq’s national intelligence service, working closely with Britain and America on fighting Isis. Western diplomats describe him as a competent administrator, a quality not found in abundance among Iraq’s political elite.

Tehran, which hosted Kadhimi on an official visit last week, is less impressed. Some in the Iranian camp even suspect that Kadhimi might have been the one who tipped off the Americans about Soleimani’s whereabouts on the day of the airstrike. This is denied by Kadhimi’s allies, who insist that being pro-western does not mean being anti-Iranian. Like many Iraqis, they say, he’s just fed up living under foreign influence, either from Tehran or Washington. Yet his first moves do suggest that he’s keen to keep Iran at bay.

Kadhimi has started reining in the Popular Mobilization Forces, the official name for the Shia militias. They currently number nearly 150,000 — roughly the same size as the Iraqi army. The PMFs were formed six years ago as volunteer units to fight Isis, but many take orders directly from Tehran. Last month, he ordered the arrest of 14 members of one of the most notorious units, the Kataib Hezbollah, blamed by Washington for numerous attacks on coalition bases. Most of the militiamen were then released, not long after their comrades staged a show of force at Baghdad’s Green Zone. But some saw it as at least a warning.

Thus far Kadhimi has enjoyed a honeymoon with the Iraqi public, with polls giving him up to 60 percent approval ratings. Unlike some of his plodding predecessors, he has a journalist’s knack for the soundbite. And his human rights background goes down well with the youthful protest crowd.

[special_offer]

However, being smart, personable and moderate is no guarantee of success in Iraqi politics. Unlike the clerics, tribal sheikhs and warlords who dominate the parliament, Kadhimi is an independent, with no party machine to back him up when things get rough. He’s pledged, for example, to prosecute the militias blamed for shooting protestors last year, and to launch a government anti-corruption drive. But the administration is a Balkanized collection of ministries, most run as corrupt private fiefdoms for different political groupings. Reform will get pushback from entrenched interests.

‘His analysis of the problems in Iraq matches our own,’ said the western official. ‘However, the flip side of him having spent time in the West is that he hasn’t spent 20 years building up a power base in Iraq, which will make things hard for him as PM.’

Still, Kadhimi is likely to try hard, not least because he has little choice. His government is broke because of the collapse in oil prices caused by COVID-19, making it heavily dependent on Washington for continued financial support. He is likely to warn other Iraqi MPs that if they don’t fall into line with his reform agenda — particularly on the question of reducing Iranian influence — Trump may pull the plug. The President may have many problems at the moment. But the Middle East, despite what everyone feared, is probably not the worst of them.

This article was originally published onThe Spectator’s UK website.