In April 2017, a group of students at Dartmouth College met with Dr David Bucci to complain about sexual harassment in the department of psychological and brain sciences that he chaired. The allegations didn’t sound particularly grave — none of the students complained of rape, for instance — but Dr Bucci flagged it up with the Title IX office even so. It was that office’s responsibility to follow up sexual harassment complaints and it duly did, suspending three professors and mounting several investigations.

You can imagine Dr Bucci’s surprise, therefore, when seven female students named him in a lawsuit they filed against Dartmouth 19 months later, accusing him of ignoring the original complaint. In the 72-page legal document, which did now charge one of the professors with rape, Dr Bucci was named 31 times. The plaintiffs were seeking $70 million in damages.

Twenty years earlier, David Bucci had suffered a mental breakdown, but he’d managed to rebuild his life with the help of medication and therapy and was now happily married with three children. Nonetheless, he found the lawsuit deeply distressing, particularly when his name started appearing on Twitter accompanied by hashtags like #MeToo and #TimesUp. Dartmouth’s lawyers advised him not to respond publicly, which he wanted to do, and he reluctantly complied. The furor on Twitter continued to build, with students, alumni and faculty members demanding he be fired under the banner of #DartmouthDoBetter. A woman at his local food co-op called him ‘a disgusting human being’.

Not surprisingly, Dr Bucci’s mental health began to deteriorate and, last year, he was hospitalized for depression and treated with electroconvulsive therapy. Dartmouth’s lawyers strongly rebutted all the allegations against him and the faculty dean sent an email to the department expressing her complete confidence in him, but it did little to stop the workplace mobbing. When it looked as though Dartmouth was intending to settle, Bucci urged the college to extract a statement from the plaintiffs proclaiming his innocence. But when the settlement came — awarding the women $14.4 million — there was no such clarification. The following month, in October 2019, David Bucci took his own life.

The 50-year-old Dartmouth academic was the latest victim of ‘cancel culture’, a digital version of public shaming that has claimed the lives of several dozen victims and ruined those of thousands more. Last year, at least one other man committed suicide after being #MeToo’d — Alec Holowka, the creator of the video game Night in the Woods — and a list of the canceled included Woody Allen, who lost his movie deal with Amazon; Kevin Hart,who was forced to stand down as host of the 2019 Oscars; and Shane Gillis, who was fired from Saturday Night Live. In the case of the last two, their unpardonable sin was to have told inappropriate jokes.

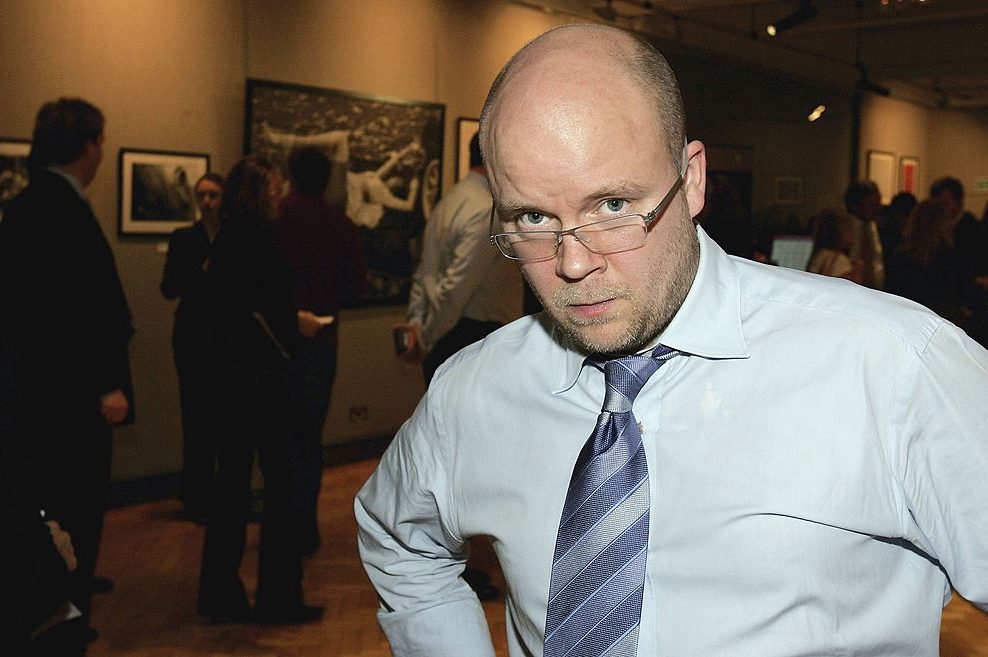

To say I know how David Bucci felt would be an exaggeration, but I do know what it’s like to be put in the digital stocks. In January 2018 I was targeted by an outrage mob on social media following my appointment to the board of a new higher education regulator by the British prime minister. As a Brexit-supporting, middle-aged, conservative, white, heterosexual male, I wasn’t exactly a popular choice with the English university sector and the offense archaeologists quickly went to work, sifting through everything I’d ever written or said in my 30-year career as a journalist. They were looking for evidence that I was unfit for public office and they didn’t have to search very hard.

For instance, I’d written a piece for The Spectator in 2001 praising a TV show on the obscure cable channel Men and Motors, because it featured topless girls draping themselves over fast cars. The copy editor, who was a friend of mine, gave it the headline ‘Confessions of a Porn Addict’ — his idea of a joke. I thought it was funny, too, until it came back to bite me in the butt 17 years later. An online metal detectorist found it in The Spectator’s digital archive, stuck a screengrab on Twitter and within minutes London’s main evening paper turned it into a news story. ‘New pressure on Theresa May to sack “porn addict” Toby Young from watchdog role,’ ran the headline.

Seven days after the appointment was announced, my suitability for the role had been debated in parliament, an online petition calling for my sacking had attracted 220,000 signatures and a posse of journalists was permanently stationed at the end of my front yard, ready to pounce on my wife and four children whenever they left the house. I resigned from the board of the regulator and apologized for my sophomoric scribblings, hoping that would draw a line under the affair. But that turned out to be naive. I subsequently had to stand down from the board of a charter-school chain I’d set up, give up my position as a Fulbright commissioner, abandon my fellowship at Buckingham University and fall on my sword as the head of an education charity. That last one was the job that paid the mortgage. It was a vertiginous fall from grace, like something out of a Tom Wolfe novel. In December of that year I didn’t get a single Christmas card.

Unlike David Bucci, I never felt suicidal. I don’t have a history of mental health problems, which helped, and even though I was expelled from the world of charities and public service — the respectable world, as it were — it didn’t have much impact on my journalism career. Louis C.K. said that when he got canceled, people used to shout at him on the street, but that only happened to me once and after that I took to wearing a trapper hat whenever I left the house. Not that I did leave the house very often — invitations came there none. With no organizations to run and few social obligations, I took up exercise to fill the time. The upshot was that between January and December I lost almost 30lb, which was therapeutic. I was able to tell myself that something good had come out of the whole experience: the public humiliation diet.

Another of the benefits of being canceled — believe me, there aren’t many — is that you end up making contact with other people who’ve been through the same experience. The New York Times ran a piece on this last November, which featured several Spectator contributors: ‘Those People We Tried to Cancel? They’re All Hanging Out Together.’ That’s not quite true, but I did meet about a dozen of my fellow malefactors in Toronto at the beginning of 2019 at a party held by Quillette, an Australian online magazine that functions as a kind of support group for the publicly shamed. Claire Lehmann, the editor-in-chief, has never been socially ostracized herself, but she acts as a mother hen to journalists and academics who’ve found themselves ex communicated for saying the wrong thing. Three months after my fall from grace she offered me a job as an associate editor, which is how I came to be at the party.

One of the deplorables I bumped into was Stephen Elliott, a writer and filmmaker who told me his story of being falsely accused of rape. In 2017, his name was included on the ‘Shitty Media Men’ list, a McCarthyite document circulated by a former assistant editor of the New Republic called Moira Donegan. The entry for Elliott read: ‘Rape accusations, sexual harassment, coercion, unsolicited invitations to his apartment, a dude who snuck into Binders???’ (Binders is a Facebook group for women writers.) His accusers were anonymous and there was no corroborating evidence, but it was enough to end his career. He lost potential Hollywood and advertising jobs, speaking invitations were rescinded, essays and short stories he’d written were unpublished, his literary agent dumped him, and close friends stopped returning his texts and emails.

He became a shut-in and a drug addict and, when his savings ran out, his thoughts turned to suicide. He felt helpless, he explained: ‘How do you rebut an anonymous rape allegation?’ His liberal friends refused to take his side because it has become a sacred principle of the #MeToo movement that we should ‘believe women’, even though in this case we don’t even know if his accuser is a woman.

He put together a suicide kit and did a ‘trial run’ that involved driving to the top of a hill near his house, smoking a lot of pot and fastening a plastic bag over his head. But, mercifully, he had a change of heart. He put his life back together and, in due course, decided to retaliate against the architect of his misfortune. In October 2018 he filed a $1.5 million lawsuit in New York against Donegan and some of the other women who’d contributed to the Shitty Media Men list.

Elliott’s courage has inspired me to mount my own fightback against cancel culture and this month I’m launching the Free Speech Union — a mass-membership organization based in London for people who feel their speech rights are in jeopardy. Our concern won’t primarily be with the laws around free speech, although they could do with being toughened up in Britain. Rather, our focus will be the Maoist climate of intolerance that’s enveloping our institutions. Last year, Cambridge University offered a visiting fellowship to Jordan Peterson, but withdrew it when he was photographed standing next to a fan wearing a ‘Proud to be an Islamophobe’ T-shirt — and that’s the tip of the iceberg. Boris Johnson succeeded in defeating Karl Marx at the ballot box, but Antonio Gramsci continues to sweep all before him in the cultural arena. The Overton window is getting narrower by the day and we need to do something to make it a little wider.

One of the benefits of full membership will be access to a legal insurance scheme: if we think you’ve got good grounds for a lawsuit, we’ll take it on. In addition, we’ll use the tactics of the Twitchfork mob against them. So if they gang up against someone on social media, we’ll gang up against them. If they launch an online petition calling for someone to be fired, we’ll launch a counter-petition. Same goes for open letters. The enemies of free speech hunt in packs; its defenders need to band together too.

I hope the Union won’t just attract male, pale and stale conservatives, but liberals who’ve been judged insufficiently woke by their left-wing colleagues. I’m thinking of feminists like Germaine Greer and Julie Bindel who’ve found themselves under attack — sometimes literally — for challenging trans orthodoxy. In the academy, the professors most likely to be canceled are old-fashioned leftists like Bret Weinstein, the biologist who was hounded out of Evergreen State College in 2017 for refusing to comply with a student edict demanding all white people remove themselves from campus for a day. The message I hope to get across to liberal renegades is: free speech is for thee and not just for me. We will welcome mavericks and dissenters of all stripes.

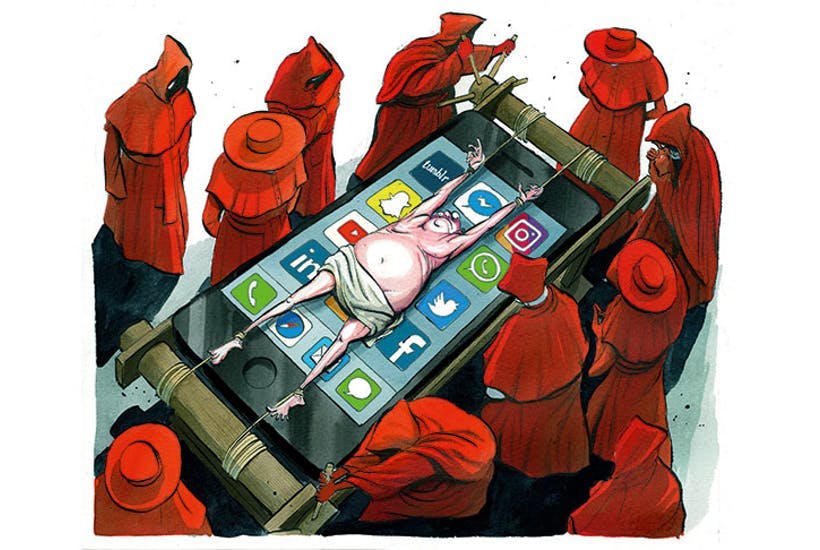

Judging from the response I’ve had so far, there’s a real desire on the part of people from across the political spectrum to fight back against this resurgence of authoritarianism. You could feel how much appetite there is for a resistance movement from the overwhelmingly positive reaction to Ricky Gervais’s opening monologue at the Golden Globes in which he took on the Torquemadas of the Woke Inquisition. Let’s make 2020 the year cancel culture gets canceled.

This article is in The Spectator’s February 2020 US edition.