Kharkiv Oblast, Ukraine

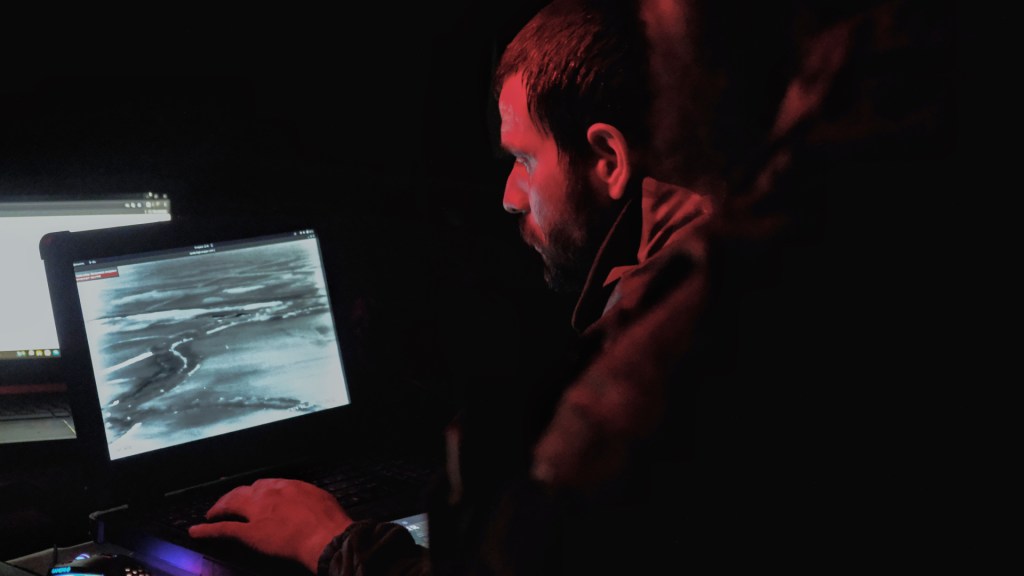

Moonlight shines on the wings of the reconnaissance drone as it glides over the field. Within minutes, the Leleka — Ukrainian for “stork” — crosses the border into Russia’s Belgorod region. The soldiers monitoring it wait in their car, hidden in the undergrowth. Soon the image on their laptop freezes: the Russians are jamming the signal. They maneuver the Leleka back and forth, eventually finding a gap in the enemy’s electronic defenses. The drone is back in contact, sending footage of Russian roads and towns. The hunt for enemy troops begins.

Some 30,000 Russian soldiers are amassed north of Vovchansk, a Ukrainian border town that was attacked two months ago. It is now split in two, with Russian forces occupying one half but struggling to advance beyond the aggregate plant in the town center. I’m with Ukraine’s seventy-first Jaeger Brigade’s drone unit, which is tasked with locating Russian weapons and vehicles before the army breaches the border. The Kharkiv region is Vladimir Putin’s second front. He has had mixed results so far, but a new push is still expected this summer.

“Even more Russian soldiers arrived in recent weeks,” says Noha, the commander of the drone unit. “They are regrouping for something larger. An order seems to have come to push us away from the border, so we wouldn’t hit there.” Putin has said he is carving out a “buffer zone” to protect Russia from Ukrainian attacks, but the real aim has been to extend the front line to stretch Ukraine’s resources. The threat of losing Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second-largest city, meant elite units were redeployed to the north, away from Donbas in the east. Now Russian troops are capturing village after village in the Donetsk region.

The only way to capture territory is for the infantry to advance, so the scene is set for a brutal trench battle

Putin’s plan has worked, then, but at a cost. British military intelligence estimates that Russia has lost more than 70,000 troops (dead and wounded) in the past two months. Opening the front at Kharkiv has stretched Russian resources too.

To fend off the new offensive, the US gave Ukraine permission to fire American weapons across the border into Russia. Ukraine-made drones are bombing just over the border, while western missiles are reserved for targets further into Russian border regions. After the first American HIMARS launcher destroyed an S-300 missile system in Belgorod more than a month ago, rockets stopped flying towards Kharkiv. The US has said it is ready to authorise attacks deeper into Russia if Putin tries to expand the front again.

Russia’s response is to use its citizens as human shields. “Russians station their artillery under houses, along roads where Russian people drive, where public transport runs,” says Noha. If western weapons cause civilian casualties, Kyiv would be in trouble. Hence the importance of drone imagery: to check whether a potential target is worth attacking and what weapons would be suitable. “Even if the video freezes due to anti-drone measures, the Leleka’s flash drive records everything,” Noha says. “If the drone returns, we get the highest quality picture and decrypt it before morning.” There are 500 Leleka crews spread across the front, conducting reconnaissance missions.

“After we destroyed some of their automatic artillery, Russians began to hide more and move away with the equipment. They do not come so close any more,”!says Noha. Battle–hardened Russian soldiers stay behind while the fresher recruits, who are considered less valuable, are sent to attack. “Some try to break through. Well, they don’t go far.”

Vovchansk isn’t the only new front that has opened in the north. Russia also is trying to capture Lyptsi, a village about twenty-three miles west of here, and nineteen miles north of Kharkiv — soldiers call it the “gate to Kharkiv.” If it falls, the Russians will be close enough to flatten the city with artillery fire as they did Bakhmut and Avdiivka. There are just two miles of territory between Russian troops and Lyptsi. The Ukrainians defending the village are bombarded by dozens of powerful glide bombs, dropped from Su-34 aircraft. These can destroy any fortifications.

“Last night, Russians dropped at least fifteen glide bombs on us,” says Roman, commander of the mortar unit of the Spartan 3rd Operational Brigade, which is stationed half a mile from Lyptsi. We are sitting on soldiers’ mattresses in the cellar of an abandoned house. As we talk, the explosions are incessant. The glide bombs, Roman says, will destroy Lyptsi. “There will be no houses. Nowhere to hide. No place to turn into a position. It will be like in Robotyno [a village in the Zaporizhzhya region], where our soldiers come in and go out, and the Russians come in and go out. There is no way to gain a foothold there — the village was simply leveled.”

Ukraine does not have the means to intercept the glide bombs, but the planes carrying them can be shot down with the F-16s that are due to arrive shortly. These jets will bring new opportunities but also questions about how they can be kept safe. Not long ago, a Russian drone spotted six Ukrainian Sukhoi Su-27 fighters stationed at a base, and in no time an Iskander missile barrel had destroyed two of them and damaged the rest. From the moment the F16s arrive, Russia will be bent on their destruction.

Lyptsi is built on high ground, which makes it hard to capture. Russian troops attack in small groups of up to five soldiers. They capture a position, dig in, and wait for a second group to bring provisions and ammunition. “One group might have a person without any weapons at all, just with a shovel,” says Roman. “Their task is purely to dig, dig, dig.” When enough soldiers gather in one place, they advance further in larger numbers. When I ask about the likelihood of Lyptsi falling to the Russians, Roman seems optimistic that it can hold: “Our soldiers, I think, have already secured themselves well. I don’t think there are any chances for them.”

Both sides have been devastated by artillery, mortars and drones. Ukraine’s ammunition is scarce, but the situation is improving. One commander told me that, at one point, they only had ten shells per day for a dozen howitzers. Now, thanks to US aid and the Czech initiative to provide half a million shells this year, stocks are replenished nightly. Russia’s artillery advantage over Ukraine has shrunk from 10:1 to just three to one in the last few months.

The only way to capture territory is for the infantry to advance, however, so the scene is set for a brutal trench battle. A couple of miles away from the front, I meet Alezhka, a soldier in the thirty-sixth Marine Brigade. In any other campaign, he would already have been discharged for his war injuries. “My leg doesn’t bend here, you see, and it doesn’t bend here — the screw is set here. I can walk, I can’t run,” he says.

One of his roles is to train new recruits. Real war, he tells them, is far from the romanticized version they have seen in films. The first close battle is decisive and fear is dangerous. “They see a Russian coming, they start throwing up or just freeze.” Sometimes there is no time to prepare. “We basically dig everything with our own strength, chop the ground to get a little bit of a foothold.” Alezhka waves a hand to indicate the thick forest around us. In such a setting, building fortifications is a nightmare.

Besides needing more weapons, Ukraine has to contend with exhaustion, dwindling motivation and a large shortfall of new recruits. Initially, a conscription law that was voted for in April was intended to grant a two-year leave to those who had fought for thirty-sixth months, but this amendment was removed from the final version. Instead, Ukraine’s parliament promised it would be included in a future vote. Soldiers are skeptical about such a promise: if it were approved, thousands of men would retire from the Ukrainian army. A potential solution would be to let soldiers rest for a few months instead of years — but even then there aren’t enough reserves to replace them. “It’s some kind of prison,” says Alezhka. “You got into this army, you’re doing your job, but what’s next? What if the war lasts for twenty years?”

At least 44,000 Ukrainian men have left the country illegally since Russia invaded in 2022, according to border authorities in Moldova, Romania and Slovakia. “But what happens then?” asks Alezhka. “The Russians will come to their home eventually. They will find everyone and enter every house. Someone has to hold the line.”

Olexandr, a chief sergeant of the thirty-sixth Marine Brigade, tells me it’s a miracle that the front line in Kharkiv has held. The delays in western aid led to Ukraine losing many more skilled and motivated soldiers than it should have. “Our golden elite, those wonderful men who could have defeated the enemy, are now dead… While the weapons kept being delayed, we are paying with the blood of our soldiers. If Ukraine falls, Russia will become far stronger because they will have absorbed us. And who, then, will stand to fight as we do now? The West’s best hope of peace is to give us everything we need now. Otherwise, in five or seven years the West will be fighting against me and my son.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply