Once, museum curators saw their job as collecting, conserving and displaying to the public works of art or humbler objects that were beautiful, interesting and representative of a time and a place. Now many of them want to get rid of, or at least hide away, objects that they pronounce shameful. Cambridge University, under its present administrators, has been following the fashion. The Fitzwilliam Museum has taken down a painting by Stanley Spencer — “Love among the Nations” — on the grounds that “Raised on the moral rightness of British imperial rule, Spencer imagines civilization firmly in the West and savagery in its colonies.” So that’s you dealt with, Spencer.

The Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology — a small treasure-house of objects from round the world — decided to dispose of 116 “Benin Bronzes.” However, what was planned as the rapid “restitution” of ill-gotten gains seems to have run into difficulties and has been postponed until October. No reasons have been made public, but it seems likely that those who made the original decision have suddenly realized that it raises issues more complex than they supposed.

The Cambridge authorities were keen to go along with the Benin Dialogue Group, which after originally advocating a program of loans, has for some time been promoting complete transfer of ownership. The university agreed to this in principle even before a formal request had been made. When that request came, in January 2022, it was in the name of the “Federal Republic of Nigeria,” and the clear understanding was that the bronzes would become state property to be held in a public museum.

The main Cambridge proponent was Professor Nicholas Thomas, the director of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, whose interests “range widely over art in Oceania, European travel, colonial histories, museology and the history of collections.” His report to the relevant university bodies stated that in a “colonial intrusion” motivated by a “trade dispute,” a British force “sacked the city and assembled loot.” The hierarchy of university committees, culminating in its highest ruling body, the University Council, duly rubber-stamped the decision to hand over the bronzes.

At no point does any African specialist seem to have been consulted. Nor did any of the committees see the necessity of obtaining a proper valuation of the artifacts being given away. This was, said the “pro-vice-chancellor for community and engagement” who presented the final case, difficult to do. Yet the total value might well be considerable, even by Cambridge standards: surely running into the millions.

The reason for this summary decision was clear — the bodies concerned were persuaded that they had a “moral obligation” to give away these 116 works of art. Not only that, but there were questions of publicity. As other museums were doing the same, Cambridge risked “being out of step” by delaying.

The question of “moral obligation” is crucial. The university specifically recognized that it had no legal obligation to donate the objects to Nigeria. The moral argument was also used to persuade the Charity Commission to approve this huge ex gratia gift. Much, therefore, turns on the circumstances of the 1897 expedition.

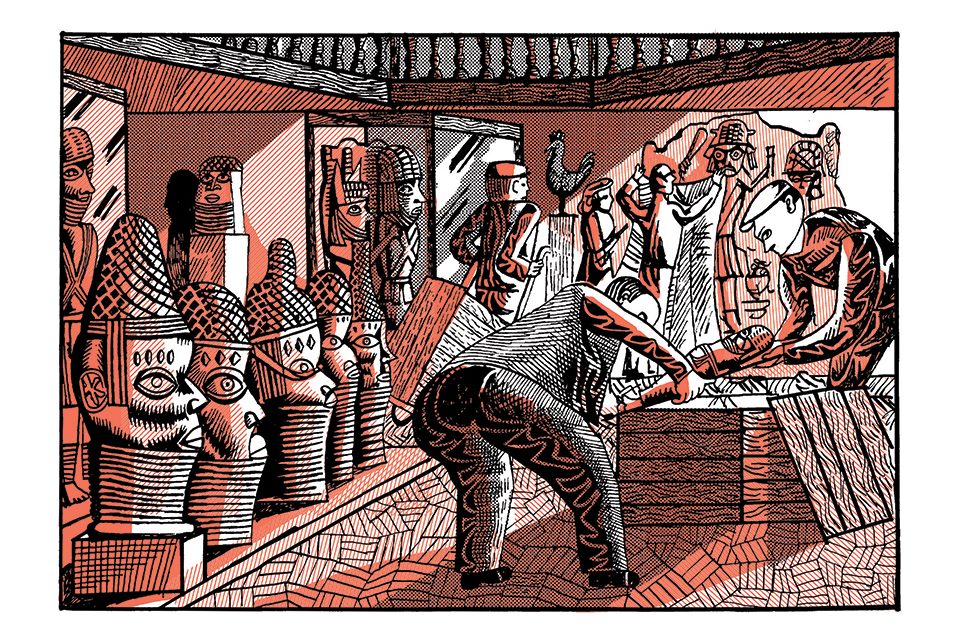

To describe it as a “trade dispute” leading to the “sack” and “looting” of Benin by a British force is, as some readers will know, rather economical with the truth. The expedition was a response to the massacre of a peaceful diplomatic mission and a large number of African porters. The “trade dispute” was an act of aggression against neighboring peoples by the Oba (king) of Benin. Benin itself was a violent, slave-holding and slave-raiding society. When the punitive expedition reached Benin, it found hundreds of dead and dying slaves, some beheaded, crucified or disemboweled. The expedition’s shocking sketches and photographs exist. The British expedition (mainly African soldiers) ended the Oba’s mass human sacrifices and liberated many slaves.

As was then legal, the expedition’s commanders seized the Oba’s personal treasures — carved ivory tusks as well as the famous bronzes — to defray its costs, and doubtless to weaken the Oba’s cultic power. Some bronzes, many of them busts of royal ancestors, were covered in the blood of sacrificed slaves.

This, it might be thought, would affect any assessment of “moral obligation.” Other recent developments do so no less clearly. Last week at Cannes, the Restitution Study Group (RSG), representing descendants of West African slaves, premiered a short film asserting their moral right over the disposal of these objects, made of brass the Obas gained by the sale of their ancestors. The RSG vehemently objects to the bronzes being returned to the successors of slave owners and traders in Nigeria, and instead wishes them to stay in western museums where they are accessible to all, including the descendants of the slaves whose bodies purchased them, and where the shocking story of the bronzes can be fully explained as a memorial to those who suffered.

The RSG claim was given added force by the president of Nigeria’s decree that the bronzes obtained from western museums would be given to the present Oba of Benin as his personal property. This has already caused backtracking by museums in Germany which were also involved in “restitution.” For the slaves’ descendants, donating the bronzes to the Nigerian state would be bad enough, but to give them to the Oba adds insult to injury.

If “moral obligation” cannot be seen as absolute, or even plausible, then other things must be considered, such as the security and accessibility of any donated or loaned works of art. As a major collection of bronzes assembled by the colonial authorities for the Nigerian state at independence seems in large part to have disappeared (one choice item was illegally presented to the late Queen and is now in the Royal Collection), to agree to the unconditional handover of Cambridge University property appears indefensible. Perhaps the university has belatedly realized this. It should explain itself to its members and to the public, who might otherwise conclude that it cannot be trusted with the treasures in its care.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.