The oddities of Joe Biden’s third presidential campaign are impossible to ignore. He is the oldest man ever nominated by a major political party, and the first nominee since 1992 to lose both Iowa and New Hampshire. He has been in seclusion inside his Delaware home since March, rarely venturing out of his basement. After winning the primary as a moderate, he has tacked left for the general, reversing the traditional sequence of presidential nominees.

Nor has Biden played it safe as his lead grows over President Trump. On the contrary: he has become more ambitious. In April, in a bid for the Bernie Sanders vote, Biden proposed lowering the age of eligibility for Medicare and forgiving some student loan debt. The following month, in another effort to unify Democrats, he created six policy task forces and filled them with several prominent members of the party’s left wing, including Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. The task forces released their findings in July. The left didn’t get everything it wanted. But it got enough.

Biden is said to chat with Elizabeth Warren on a regular basis. His campaign, in a revealing contrast, downplays Biden’s conversations with Warren’s opposite number in the party, former Treasury secretary Larry Summers. On the Fourth of July, Biden pledged to ‘rip the roots of systemic racism out of this country’. The next day he tweeted that after he defeats Trump, ‘We won’t just rebuild this nation — we’ll transform it.’ Into what, he did not say.

The combination of Biden’s age and leftward turn has electrified liberals and anguished conservatives. ‘Biden might now be willing to depart from the economic principles that have governed policy-making in this country over the last 40 years: the so-called neoliberal principles of free markets, little government intervention or investment, wariness about deficits, and more,’ wrote Michael Tomasky in a July issue of the New York Review of Books. If the current mix of trade wars, trillion-dollar stimulus packages and a deficit running to some $4 trillion counts as ‘neoliberal’, we are in more trouble than I thought.

What worries the right is Biden’s tepid response to the tsunami of protests, vandalism, cancellations and political correctness that has washed over the country in the weeks since the police killing of George Floyd. Biden has said he is against defunding or abolishing the police, and that statues of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Christopher Columbus deserve protection, while monuments to Confederates belong in museums. His Independence Day message reduced American history to an unending conflict between racism and equality, and featured images from Black Lives Matter rallies. But he did not endorse the movement’s radical demands.

Biden’s positions are in the mainstream. Public opinion backs him. But what if Biden is not the one in charge? His age, mental condition and references to serving as a transitional figure for a rising and more progressive generation of Democrats unnerves Republicans. They say a President Biden would surrender to the left and be dumped at the first opportunity.

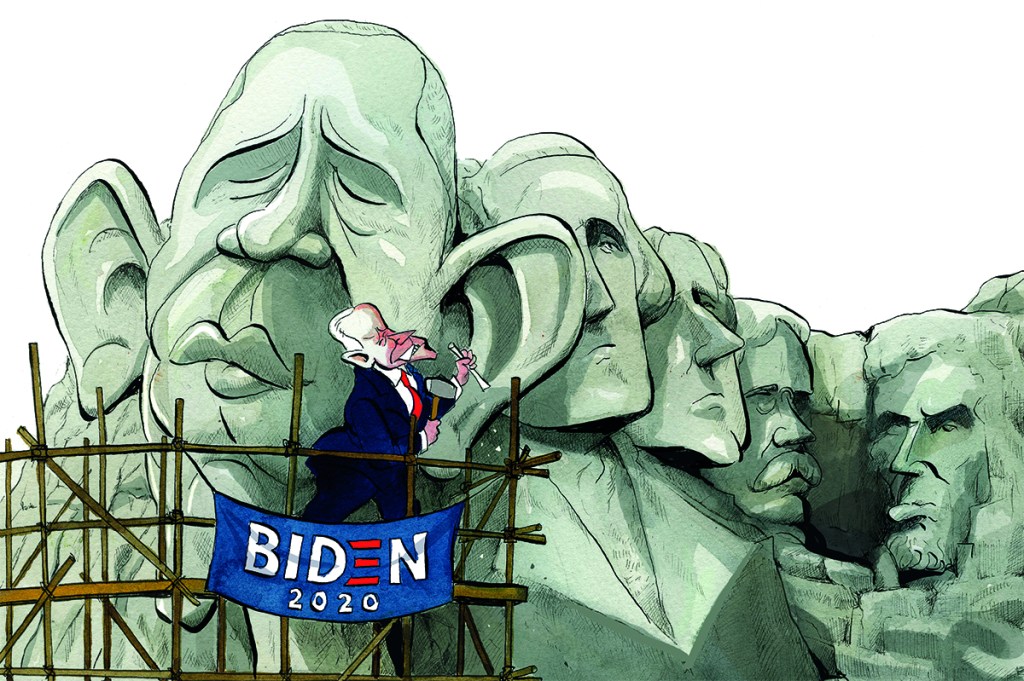

Former senator Judd Gregg advanced a perfervid version of this idea in the Hill during the second week of July. ‘Within a few months of assuming the presidency,’ he wrote, ‘Biden may find himself being the next statue toppled as the socialist/ progressive movement moves closer to power.’ Biden’s woke vice president and cabinet, Gregg continued, might invoke the 25th Amendment and throw poor Joe overboard. ‘It will be a coup.’

The left wants Biden to be another FDR. The right fears he’s the second coming of Alexander Kerensky: a figurehead unable to control the revolutionary forces from which he initially benefited. I doubt either prediction will come true. If he becomes America’s 46th president, Joseph Robinette Biden, Jr is going to face the same constraints as his predecessors: a quarrelsome Congress and an independent judiciary, a brief window to pass a legislative agenda and an electorate happy to rebuke parties that mistake electoral majorities for ideological ones.

Biden would also have to manage the peculiar coalition that put him in office. Moderates, suburbanites and independents supply the votes, and moralistic and unappeasable social justice warriors dominate cultural, media and corporate institutions. This risky balancing act would be a minor feat in comparison to pulling off the immediate and overwhelming tasks of suppressing the coronavirus and restoring the economy.

It is hard to identify Biden’s legislative priorities. His campaign has been more about personality, character and a certain idea of America than it has about policy specifics. Not that Biden lacks proposals. His website features 41 sub-categories of ‘Joe’s Vision’, from ‘The Biden Plan for Climate Change’ to ‘Joe Biden’s Agenda for the AAPI Community’. (It stands for ‘Asian and Pacific Islander’.) The question is what Biden would lead with.

Each of the post-Cold War presidents has opened his term with an economic package. On July 9, in a clever turn in the direction of the economic nationalism associated with the Trump administration, Biden unveiled a proposal to close ‘Buy American’ loopholes in federal procurement law, and to spend hundreds of billions on research and development. He signaled that his first months in office will concentrate on taxes and spending.

After the economy, Presidents Clinton, Obama and Trump turned to healthcare, with mixed results. There is no reason to think Biden would act differently. Finally, Biden has made certain commitments in the energy sector — net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 — that require congressional approval. If he is able to sign these three bills before the 2022 midterms, he would be on his way to a successful term.

Emphasis on ‘if’. Biden’s forebears learned the hard way that Congress has a mind of its own. Party affiliation does not matter. Democratic congresses rejected Clinton’s health bill and Obama’s cap-and-trade plan. A Democratic Senate denied Obama his public option. A Republican congress failed to repeal Obamacare under Trump.

Biden’s task is difficult because Democratic majorities rest on districts and states that swing from red to blue and back again. That will make them reluctant to adopt the recommendations of AOC’s unity panel. In June the Cook Political Report classified 10 Senate seats as either toss-ups or leaning Republican. Nine of them are in states where Trump won at least one electoral vote in 2016. (Maine divided its votes.) In a Panglossian scenario where Democrats win them all, Chuck Schumer would still be four ayes short of a filibuster-proof majority.

Schumer might try to abolish or curtail the filibuster, of course. He has flirted with the idea before. But Schumer must also understand the risks. Going after the filibuster would initiate a polarizing and high-stakes battle that has the potential to divide his caucus, and to distract from and damage Biden’s post-inaugural honeymoon. It would be an easy way to resuscitate the right from its post-election doldrums. The coverage would be brutal on Fox News Channel. And on Trump TV.

If Congress stymies him, Biden may pursue his objectives through executive orders and the bureaucracy. Here too, Biden would be following the examples of Obama and Trump. And here too, he would run into similar obstacles. Attempts to overturn the Trump legacy will consume the early months of his presidency. Republican state attorneys general and the conservative legal movement will challenge the constitutionality of regulatory maneuvers. Just wait until a district court judge, when ruling against a Democratic administration, discovers the appeal of the ‘nationwide injunctions’ that have bedeviled President Trump. Nor will Biden be able to rely on appeals. Neither Obama nor Trump got all they wanted from the Supreme Court. They often got less.

Biden won’t have much time to act. Midterms are not kind. The president’s party has lost seats in all but two of the 19 midterm elections since 1946, and the average loss is in the double-digits. It is no mystery why. The Stanford University political scientist Morris Fiorina has pointed out that overreaching majorities are a feature of the post-Cold War era. Beginning with President Clinton, parties have assembled majorities based on appeals to marginal (and non-ideological) voters only to alienate those voters when the majority, once in office, pursues ideological goals. In a half-century as a professional politician, Joe Biden has given no indication that he knows the solution to this puzzle. If anything, he is part of the problem.

Partisans like to assume that when an election goes their way, the voters have endorsed the totality of their visions and dreams. That is not how politics works. As the adage goes, oppositions do not win elections. Governments lose them. A Biden victory would not be an affirmation of his party. It would be a negation of Trump’s. The incumbent was favored by betting markets and running competitively in swing states until March. Biden’s strict observance of social distancing did not change the dynamic. Trump’s mishandling of the coronavirus and urban crises did.

[special_offer]