Young people are now more likely to consume marijuana than to smoke tobacco. The social acceptance of tobacco is falling, just as the popularity of weed is getting higher. A 2019 Gallup poll found that 12 percent of US adults (and 22 percent of those aged 18 to 29) said they smoke marijuana. It won’t be too long, I predict, before we look back in horror at the widespread acceptance of cannabis use.

It’s easy to forget that anti-tobacco researchers had to plod on at tortoise pace for years before they were able to prove what they had long suspected to be true (and what we all now take for granted): the causal link between smoking and lung cancer. Big Tobacco was so rich and powerful that its lobbying suppressed the true dangers. But the evidence kept mounting until it became irrepressible. There is every reason to presume that we’ll see the same story with dope and its ill effects.

Online, fears among users are already sprouting. /r/Marijuana, the online Reddit community of cannabis users, has nearly 200,000 members. The majority of posters on the forum appear to be frequent users. They favor liberalizing state and federal marijuana laws, and keep regular track of them by posting the latest news and opinion pieces. Yet these enthusiastic stoners also have concerns. One 21-year-old, for example, complains of ‘strange effects’ he’s been having from the drug. He has ‘always loved weed’: it’s one of his ‘favorite activities’. But recently he has been getting ‘terrible chest pain’ that feels ‘like [a] knife being stuck right under my first rib on the left side of the chest’. The hospital had no answers. Does Reddit?

This young man is not the first person to raise this question, on Reddit or elsewhere. In 2019, the New York Times reported that dozens of young people had been hospitalized across the country for ‘severe respiratory problems’ after vaping nicotine or marijuana. As well as serious respiratory problems, the patients reported ‘chest pain, vomiting and other ailments’. Doctors and medical experts were unable to identify the ‘causative agent’. They felt they had ‘no leads’, or even advice to give. Their experience or knowledge of cigarettes and cigars doesn’t really help when it comes to the new wave of marijuana and vaping products.

Meanwhile, on /r/Marijuana, one young user is experiencing ‘90%’ post-high memory loss and wonders whether he’s just ‘overdosing by accident’. Another says, ‘When I smoke weed, I feel like I’m having a panic attack. Can anyone explain?’ Another, ‘Worst panic attack on weed ever. Smoker for 12 years. Should I stop?’ And a particularly stark account begins, ‘Panic and Death feeling.’

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, the tobacco industry, which had been unregulated for most of its history, came up with various fantastical health claims. Good for the throat! Good for the nerves! Good for digestion! The landmark British Medical Journal study on the smoking habits of doctors which began in the 1950s (when 85 percent of doctors were smokers) took years to demonstrate excess mortality, and longer still to pinpoint the link with lung cancer. It didn’t help that some doctors were taking industry handouts, participating in advertising campaigns, then later conducting ‘research’ into ‘other causes’ of lung cancer. During the Great Depression, the tobacco companies even bailed out the American Medical Association. And all the while (as is now beyond dispute), millions of people across the country made the poorly-informed choice to smoke, inadvertently shortening their lives.

Toward the end of the last century, the US made the same mistake with opioids. The Sackler family’s pharmaceutical company, Purdue Pharma, became a billion-dollar blockbuster through the aggressive marketing of OxyContin, a supposedly ‘nonaddictive’ drug. As with tobacco before the Sixties, hard evidence of harm was not yet confirmed. Marketing targeted doctors as well as consumers, and many doctors became heavily involved in promotion and prescription. But in the decades that followed the brutal truth emerged about Big Pharma’s facilitation of the opioid crisis. An estimated 450,000 lives have been lost and countless more ruined.

Few seem to grasp the greediness of the cannabis industry. ‘We are Big Marijuana,’ announced Jamen Shively, a tech entrepreneur, after Washington State’s legalization of recreational marijuana in 2013. ‘We are moving forward with plans to build a national and eventually international network of cannabis businesses. We are going to mint more millionaires than Microsoft.’ In the United States alone, the industry is valued at $13.6 billion. Democrats are scrambling into bed with big business to shaft the very people they nominally represent. Gov. Andrew Cuomo of New York has just announced the allocation of a $100 million cannabis ‘social equity fund’ to ‘address and correct decades of institutional wrongs to build back better than ever before’. Cuomo heralds the ‘economic benefits’ of his Big Dope initiative and the ‘opportunity to generate much-needed revenue’. But opportunity for whom, exactly?

Neill Franklin, a cannabis reformer and law enforcement vet, is the executive director of the Law Enforcement Action Partnership. He tells me he’s ‘greatly concerned’ about Big Dope putting profits before the economic interests of people of color as the weed business goes ‘from the back room to the boardroom’. He says the industry has moved from ‘one where people of color were making the money, although illegal, selling it on street corners and neighborhoods and communities’, into the hands of Wall Street and ‘corporate America’.

I ask Franklin if he’s concerned about the consumers, given that cannabis is a cheap, down-market drug and almost certainly a health hazard. Surprisingly, he says he is ‘not really concerned about that’, since the way to get minority communities back on their feet and making good choices is with education, family services, opportunities for employment and social mobility.

But shouldn’t all that education and all those great community changes happen before we start setting up marijuana shops on street corners? ‘You have to do it simultaneously,’ he replies. ‘You have to build the plane as you’re flying. You know, you have to build the boat as you’re sailing it.’

So, whatever the vessel’s condition or readiness, whatever doubts we might have — it’s too late. The bottomless boat has left the harbor! The wingless plane is in the air! Blue and red states alike are turning various shades of green as marijuana laws continue to be liberalized across the country. Critically, however, the Food and Drug Administration can’t regulate marijuana, because it’s still federally illegal. This gives Big Dope free rein to exploit a calamitous policy misalignment, and to develop and sell products which not only rapidly outpace any regulations, but also all existing research.

Jonathan Caulkins is a professor at Carnegie Mellon University and the co-author of Marijuana Legalization: What Everyone Needs to Know. The problem with current legalization policies, he believes, is profit. He makes an interesting analogy with the blood distribution market. There are many who make a living out of collecting and distributing blood, but no one is allowed to get rich that way, because that would be ghoulish and ghastly. ‘All nonprofits have to have a charter, a mission,’ he explains. In the context of marijuana, that would mean that ‘if you want to be a player, you have to pledge that your goal is to undercut the black market, but not to expand use’. Another variation of the nonprofit model would be cooperatives, tightly regulated cannabis clubs like they have in Uruguay.

Yet even if the federal government got a grip and kicked the FDA into gear — which, recall, it did with tobacco about 70 years too late — there is still no guarantee against exploitation and abuse. And neither, despite what some say, is medicalizing marijuana in a for-profit context. After all, the FDA played a significant role in the opioid crisis by permitting the mass-marketing of OxyContin.

Another problem, Caulkins says, is ‘regulatory capture’, which is what happens when a regulated industry not only has ‘a strong interest in less regulation’, but also possesses ‘the resources to provide substantial funds to politicians who will back industry-favoring nominees for regulatory positions’. Mix in a bit of ‘straight-up corruption’, and the results can be toxic. Take Oregon, for example. When Oregon legalized marijuana (and then decriminalized hard drugs too), it appointed 15 people to its new cannabis rules advisory committee. Four appointees were growers, three provided various services to the cannabis industry and one was a county commissioner later sued for accepting industry handouts. Bribery to obtain one of the limited number of licenses also continues to be a problem, as evidenced by the FBI’s open investigations.

One /r/Marijuana user says that he witnessed ‘somebody go into a completely psychotic, blacked-out state from smoking a dab’:

‘This guy was aggressive, he force-kissed my friend, started saying the n-word over and over again (???), and he kept calling us assholes and hurling other insults at us. We took him home, and he texted us at 3am saying that he had just come down and didn’t remember anything. I should also mention, this guy is somebody who you’d meet and think they’re kinda hippyish, and he is the kind of guy who seems very sympathetic and politically correct.’

The poster would like to know: ‘Have there been any studies researching temporary psychosis caused by marijuana?’ The answer is yes.

The medical profession agrees that there are a number of basic conditions that predispose people to problematic drug use. One is environmental. If you are of a lower socioeconomic status, or if you do not have the benefits of a stable family structure, then you are more likely to develop a problem. Another is genetic (though discovery in this area is in its infancy): a latent predisposition or family history of psychosis, for instance.

Combine that context with the fact that weed is relatively cheap and can be easily integrated into an otherwise functional lifestyle and daily routine, and you have a particularly unpleasant slow-release cocktail for dependency and abuse. Of course, people will still want and use marijuana regardless, but a true choice is an informed one. Unfortunately, much of the information isn’t yet available. And it won’t be forthcoming if Big Dope has anything to do with it.

‘From a purely pharmacological perspective, it’s important to recognize that cannabis is a drug of abuse. Neurobiologically it increases dopamine release in the reward center of the brain, the same way that all other drugs of abuse do,’ says Ryan Vandrey, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University.

Similarly, a senior Scottish psychiatrist with over 30 years’ experience working in Glasgow, home to Europe’s worst drugs problem, tells me that experts and psychiatrists there are urging caution because we are conducting ‘a huge pharmacological experiment on young people’. Over the course of his career, he has encountered a ‘depressing daily reality of some wee guy who has been smoking loads of dope who is having his first episode of psychosis, whose family are devastated and whose life chances and performance is going down the pan’. He wonders if people realize what’s involved in psychosis:

‘Because it can be very unpleasant, including aggression, damaging property, being terrified, police being involved, smashing up televisions, throwing things out the window, assaulting medical staff, assaulting police; nurses getting fingers bitten or people having to be restrained by three or four nurses. But to [some people] it doesn’t sound as bad as lung cancer.’

As epidemiologists know, it can take years to demonstrate a causal relationship. There are ethical restrictions on experiments involving human subjects when the outcome is likely to be either neutral or bad. Observational studies (the alternative when clinical trials are not possible) take time, and the social or pharmaceutical context of the drug under study can change. Nevertheless, marijuana’s links with psychosis have been studied since the 1970s. While not conclusive, there is serious and consistent cause for concern.

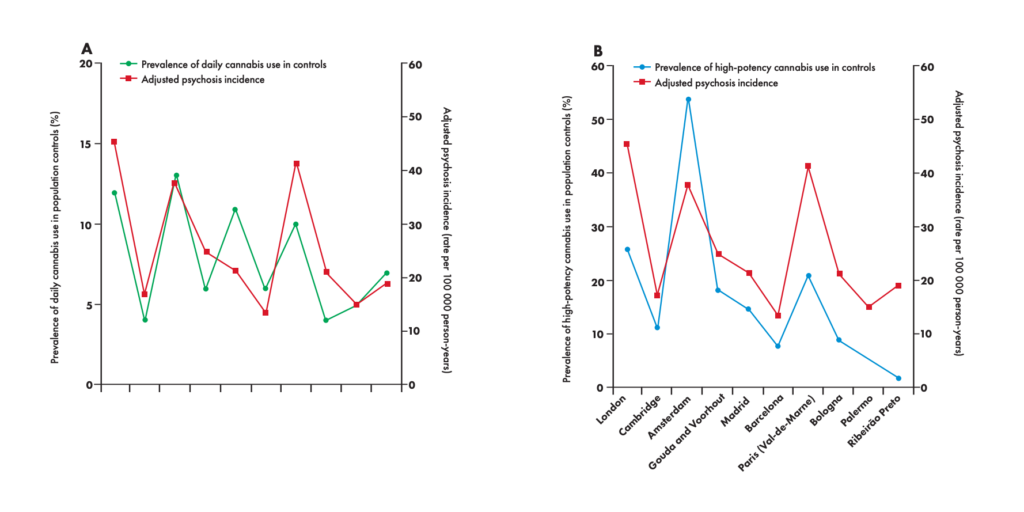

A 2008 article in World Psychiatry, the top journal in the field, outlines the results of a 15-year prospective study in Sweden examining schizophrenia in over 50,000 Swedish conscripts. It found during its 27-year followup that, if the association they identify was indeed causal, ‘13 percent of cases of schizophrenia could be averted if all cannabis use were prevented’. A more recent 2019 study in the Lancet Psychiatry examined patterns of psychotic incidence across Europe in connection to cannabis use, and found that ‘daily cannabis use was associated with increased odds of psychotic disorder compared with never users, increasing to nearly five-times increased odds for daily use of high-potency types of cannabis’. Moreover, they concluded that, assuming this association was causal (which the authors consider highly credible), as much as ‘20 percent of the new cases of psychotic disorder across all our sites could have been prevented if daily use of cannabis had been abolished’.

Do such findings, published in leading international psychiatry journals, give pause to Big Dope? Big Nope!

From the business side of things, this all makes perfect sense. Big Dope wants its customers to love its products and to use them as often as possible. So, what does it do? It makes a lot of different varieties to maintain interest. Still, no one saw the sheer volume of choice coming. People used to smoke marijuana. Now they vape it, eat it, slather themselves with it and even shove it up their asses. Because frankly, why not?

It’s no longer just some dried-out old leaf smoked by some dried-out old hippies, but wondrous fairy drops that come in all sorts of juicy and spicy flavors, forms, colors, and textures! And with unprecedented levels of THC (which determines intoxication) to boot. Johns Hopkins’s Vandrey cautions that ‘if you wanted to do this right, every single variant would be treated as its own product and would require safety, toxicological testing and need to be regulated’. That is not what is happening, obviously.

On /r/Marijuana, another user writes:

‘I’ve been smoking for about 25 years now. And within the last 8 years or so sometimes when I take a big rip (sometimes even just a regular one) I kinda black out and hear a WAWAWAWA type sound, i’ll get dizzy, my vision will get very impaired and i’ll recover in about 5 seconds.’

‘I have always attributed this to weed getting stronger since I started smoking, but is this true?’ he wonders. And once again, the answer is yes. The amount of the dose and the frequency of use are linked to higher instances of psychosis and other ill effects. Jonathan Caulkins tells me that modern doses are ‘unlike anything anybody thought about’. To illustrate this ‘phenomenal change’, he uses the example of a person who drinks 20 ounces of Diet Coke a day.For that person to increase his caffeine consumption by a factor of 70, the same way that THC concentration in marijuana has risen in the past two decades, he would have to switch from the Diet Coke to roughly 36 grande cappuccinos a day. Paracelsus’ fundamental principle of toxicology was that the dose makes the poison. So just how dangerous is this new and unprecedentedly high dose? ‘We’ll find out over the next 10 to 40 years.’

I speak with Sergeant Norm, an officer in Portland, Oregon who isn’t really called Norm. He works predominantly in crowd control. He was on the frontlines during the riots there over the summer and recalls that ‘there was almost always a thick, thick marijuana odor in the air’. He says that he has had marijuana smoke blown in his face by troublemakers, which he interprets as an act of ‘defiance’. This description seems symbolically apt for the fog of madness, the stinky green cloud now descending on America.

Cannabis evangelists are well versed in whataboutery. What about tobacco? (Well, quite.) What about alcohol? What about coffee? In some respects, they have a point. But this is what makes cannabis so different. None of the aforementioned drugs command the sort of love and loyalty that cannabis does. None have their own instantly recognizable, brand-ready leaf logo, for instance. Caulkins tells me about an observation made by his friend Mark Kleiman, author of a classic in the field, Against Excess.

Kleiman noted that in a democracy, politicians respond when people lobby their elected representatives. The tobacco industry can no longer get smokers to do that. Smokers know too much, and (let’s be honest) they sort of hate themselves. Alcohol drinkers are a lazy bunch who just don’t want a tax hike. But with weed, the users — especially the young ones, of whom there are plenty — are energetic and determined in pursuit of their cause.

Because, lest we forget it, they need a cause. A religion. And they’ve found one. As one /r/Marijuana sufferer, besieged by what he suspects to be weed-induced afflictions, cries out from the depths, ‘I dont want to quit this god of a plant. Can anyone help?’ But it’s not a matter of can they help, it is a matter of will they. For a spiritual crisis, as much as anything else, is what’s plaguing the US, here on the precipice of the smokin’, bakin’, vapin’, rubbin’ 2020s. Welcome to the brave new era of bowing down to the green stuff. For the poor, it’s marijuana. For the privileged, it’s money.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2021 US edition.