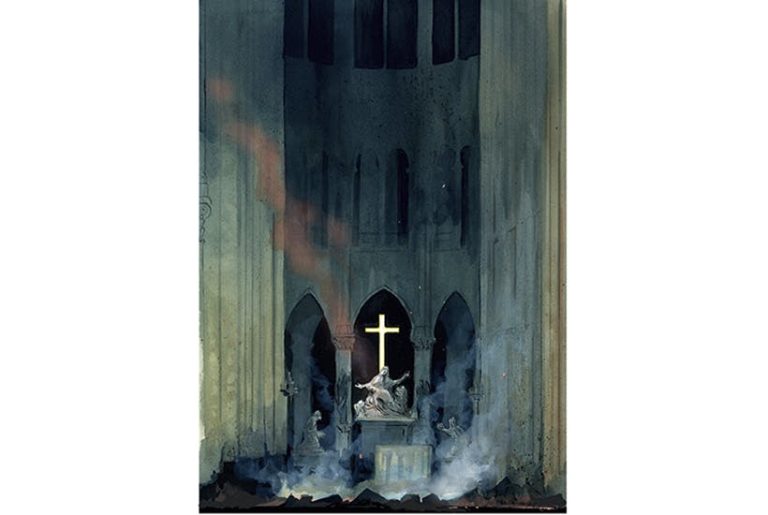

Conspiracy theories aren’t something I take seriously. But when flames engulfed Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris on the evening of April 15, 2019, my mind momentarily wandered down that path. After all, attempts to incinerate, vandalize and rob Christian churches and shrines have become so commonplace in France over the past three years that one could be forgiven for concluding that something even more sinister was afoot.

In 2017 alone, according to France’s Interior Ministry, 878 acts of vandalism were committed against Christian places of worship, cemeteries and shrines. That’s an average of nearly two and a half sites being targeted every day.

Government officials play down the problem. As one French bishop told me, they believe that directing attention to church burnings and theft could encourage copycat behavior. But, he added, they also fear publicity might fuel an existing concern among the population: that the state isn’t fully in control of law and order. This perception is underscored by realities such as no-go areas for the police in some French cities and ongoing gilets jaunes protests. Most French newspapers have acquiesced in this silence. That’s why you need to turn to organizations like the Vienna-based Observatory on Intolerance and Discrimination against Christians in Europe to discover what’s going on.

Given the surge in jihadist terrorism throughout France from 2012 onward, it’s tempting to blame Islamists for this onslaught of attacks. There are clear examples where this is the case. Last May, ‘Allahu Akbar!’ was scrawled across the door of Notre-Dame du Taur in Toulouse. In July 2018, the same words were discovered on the burnt walls of Saint-Pierre du Martroi in Orléans after it was damaged by arsonists.

Whether these and similar attacks were professionally planned or simply spontaneous acts by French Muslims unhappy with their lot in life is unclear, but 21st-century jihadists understand the psychological impact of assaults on national symbols. France’s particular religious history means that any such campaign would inevitably involve its Christian patrimony.

Other cases, however, indicate that some attacks have other causes which are less easy to categorize. Take the fire at Saint-Sulpice, Paris’s second-largest church, on March 17, 2019, which damaged its doors, a bas-relief, a stained-glass window and a staircase. Police didn’t hesitate to call the fire an act of arson. A priest at the church has since said it was started by a homeless man. If that’s accurate, it’s unlikely he was seeking to make an anti-Christian point, let alone send a political message, given the high rates of drug addiction and mental illness that plague the homeless in western societies.

A clear motivation for some incidents is theft. In 2018, 129 churches were robbed in France. It’s not hard to enter French churches, especially in urban areas. The Catholic clergy try to ensure that their churches are available for people to pray or simply take a moment for contemplation in the presence of beautiful art and architecture.

Unfortunately, this makes these churches vulnerable to those intent on stealing valuable artifacts. In 2018, a gang of Romanian thieves proved very proficient at robbing French churches of paintings and objects containing precious metals. The absence of security cameras in all but the most important of France’s churches doesn’t help.

A similar variety of motives characterizes attacks on churches in other European nations. In Germany, Catholic churches in Bad Säckingen, Rheinfelden-Nollingen and Schwörstadt experienced a series of robberies between mid-April and the start of May.

Yet other cases do seem driven by unspecified animus against Christianity. In October, more than 40 graves were smashed up at the cemetery of Our Lady Mother of the Church parish of Zabrzu-Helence in Poland. The object of the exercise seems to have been desecration itself. Sometimes this takes very direct form. On October 5, the 18th-century Chapel of La Rosa in the Córdoba provincial town of Montilla in Spain was entered by individuals who gained access to the tabernacle, extracted the hosts and flung them around the altar. Keeping in mind Catholicism teaches that the host is the body of Christ, it’s hard to believe the perpetrators didn’t know what they were doing.

Violations of Christian religious sites throughout Europe are only part of the picture. Many religious buildings have become places where all sorts of crimes happen. In Britain between January 2017 and November 2019, more than 20,000 crimes occurred on church properties. They included vandalism and arson, but also drug-trafficking, substance abuse, theft of church objects and the robbery of visitors and congregants.

Is it possible to make any sense of these assaults on Christian sites in Europe? Is there a generic dimension to the vandalism, burnings and criminal behavior?

The first thing to remember is that attacks on religious places in Europe are hardly new. Jewish sites have been targeted by anti-Semites for centuries and Christian sites have been pillaged and burnt in the name of assorted revolutions since 1789. The liberal governments of Spain’s Second Republic in the 1930s displayed profound indifference to the desecration of nuns’ graves by leftist mobs, not to mention the burning of Catholic churches — the worst case being the destruction of Oviedo’s cathedral in 1934. During the Spanish Civil War, it was effectively open season on Catholic buildings and symbols in the territory controlled by the Republic.

But it was the Marxists who elevated the destruction of religious sites into an art form. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Soviet Union made a point of demolishing synagogues, mosques and, above all, Orthodox churches. Many of those that escaped ruin were turned into museums for atheism or crop-storage facilities. According to Nathaniel Davis’s A Long Walk to Church: A Contemporary History of Russian Orthodoxy (1995), the Orthodox church administered about 300 active parishes in the USSR in 1939. Prior to 1918, there had been roughly 50,000.

There has been a leftist ideological element to some attacks on Christian-associated sites in more recent years. Here anarchists and radical feminists figure prominently. On the night of October 5-6, 2019, a feminist group claimed responsibility for breaking into the Christian-run Pro Femina crisis-pregnancy center in Berlin. The ladies concerned smashed windows, immobilized door locks by pouring glue into them, threw paint and foul-smelling acid across the hallways, and painted the slogan ‘Pro Choice!’ on the walls.

I’m inclined, however, to see something else underneath this wave of destruction: the loss of a sense of the sacred throughout so much of the Old Continent — at least when it comes to how people view the Jewish and Christian faiths which, whether one likes it or not, played central roles in developing western and European identity.

The primary purpose of religious sites is to venerate whatever deity is being worshipped. This is what makes synagogues, churches and mosques different from, say, business offices, family homes or school buildings. Some Christian confessions, most notably Orthodoxy and Catholicism, regard their churches not only as places where grace is conveyed through sacraments like baptism, confession and communion. God Himself, they believe, dwells within these edifices.

That’s why worshipers inside Orthodox and Catholic churches whisper to each other rather than chatter out loud, and remind their children to genuflect and cross themselves when entering and leaving. Christ Himself is regarded as physically present in the Eucharist, whether during Mass or in the tabernacle — a presence signified by the perpetual burning of a vigil lamp that’s only extinguished on Good Friday. So strong has been the sense that Christian churches are truly God’s house that English law recognized that fugitives in a church enjoyed a type of immunity from arrest by secular authorities from the fourth century until James I’s abolition of the tradition in 1623.

Today much of western Europe is far removed from this cultural environment. The de-Christianization of large parts of the population and public life was bound to diminish the latent sense that there is something about churches which makes them fundamentally different from other places. Many churches are now viewed as just another museum — beautiful historical buildings with many wonderful works of art, but museums nonetheless.

Lamentably these trends are reinforced by the fact that some clerics have ceased to regard their churches as places where the sacred is prioritized. In August 2019, for instance, a carnival ride was erected for 11 days inside Norwich Anglican cathedral in eastern England, though the decision to install it was pilloried by Anglican and Catholic clergy alike. The local bishop tried to defend it by saying that ‘God is a tourist attraction’. The previous month, a nine-hole mini-golf course had been installed in the central aisle of another great English cathedral, Rochester. Some things are so ludicrous that they can’t be made up.

Christianity does teach that God is everywhere in the world that he created, but Christians also believe that God wants some particular places to be given over to worship of Him and meditation upon transcendental truths. From this perspective, putting carnival rides and mini-golf courses in churches reflects a wider diminution of a sense of the divine and the very idea that there are holy places.

It’s easy to laugh at the events in Rochester and Norwich for the absurdities they are. Yet given such atmospherics and the broader disintegration of awareness of the sacred in the wake of Christianity’s decline throughout much of Europe, is it any wonder that all sorts of people — many of whom aren’t animated by jihadism or leftist ideologies — now regard churches as fair game for nihilistic vandalism, convenient places to conduct drug deals and get high, or locations to lift a valuable artifact or two to sell on the market for religious objects?

It’s uncertain how this will all end. But one thing is clear: a society in which so many people are apparently indifferent to the destruction and trivialization of its traditional holy places is surely in some sort of deeper existential crisis and arguably storing up long-term trouble for itself. And that is something which should concern all Europeans, believers and non-believers alike.

Samuel Gregg is research director at the Acton Institute and the author, most recently, of Reason, Faith, and the Struggle for Western Civilization (2019). This article is in The Spectator’s January 2020 US edition.