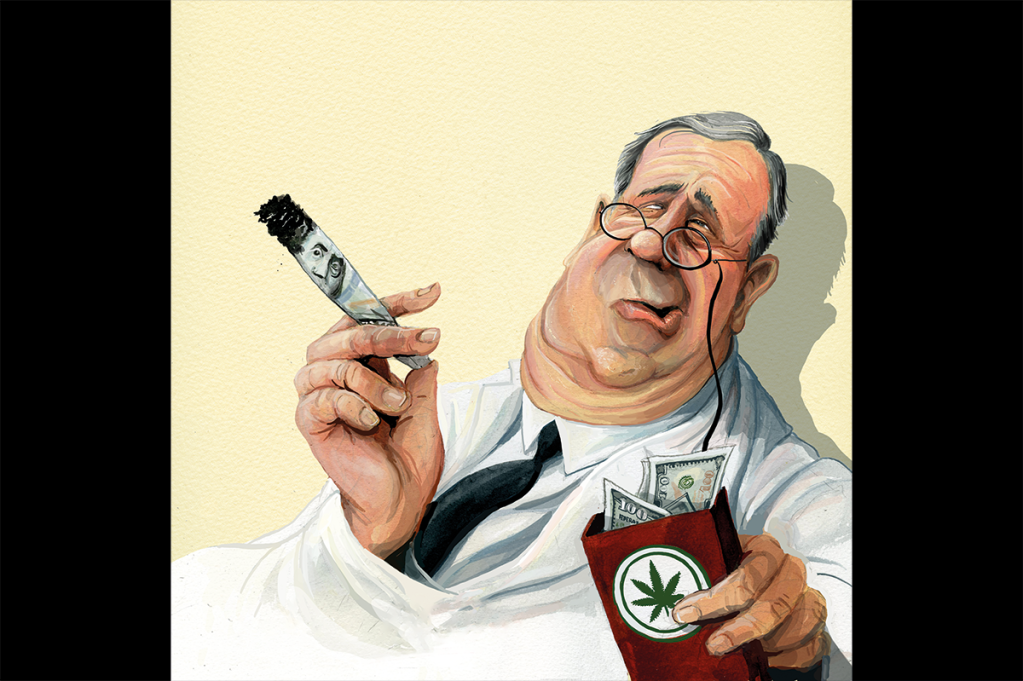

Before anyone celebrates a ban on tobacco sales to people below a certain age, we need to consider what habits might take its place. And it might not only be vaping.

Approaching the Holland tunnel in New York a few summers ago, I lowered my car window and was hit by the stench of cannabis smoke. It came from a car full of youths in the adjacent lane. More alarmingly, the smoker was also the driver of the car. In the last few years, uninhibited toking has become an increasingly common sight — or smell — everywhere.

If three of your ten closest friends use a drug, it’s an optional extra; if eight of them do, it’s a social norm

I can see many reasons to decriminalize cannabis, especially in the US where the fetish for incarceration has ruined millions of lives for offenses which would never carry a custodial sentence elsewhere. At a selfish level, I find stoned people pleasanter than drunks, or at any rate they are annoying in a less alarming way. I have watched enough episodes of Narcos to be convinced that criminalization can indeed be counterproductive. I would like scientists and inventors to be free to discover new medical applications, since potentially life-changing research into the treatment of psychiatric disorders may have been delayed by overly strict regulation of recreational drugs. I don’t know anyone my age who has suffered from cannabis use, whereas I have lost at least three near contemporaries to drink (I am fifty-eight). And so on. I get all that.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]So when I smell cannabis smoke on the streets of Britain, I don’t want the perpetrators arrested by the Babylon or hassled by The Man. But I do think we should talk about this more.

For one thing, many of life’s enjoyable yet potentially addictive behaviors suffer from “the invisible 10 percent problem.” As with alcohol or gambling, the habit may be enjoyable for 90 percent of people, but catastrophic for the remaining 10 percent, whose genes and/or personal circumstances predispose them to addiction. Worse, you only find out you are in that unfortunate 10 percent when it is too late. Frequently these victims fall out of their normal social orbit, spend most of their time with other users, and hence aren’t noticed. I haven’t encountered many people adversely affected by cannabis use, but then I wouldn’t, would I? Talk to people in the field of rehabilitation, or those with direct personal experience: you’ll find much more caution than among the chatterati.

Drugs not only affect the behavior of the people who consume them. There are strong network effects too. Apart from anything else, people tend to cluster around others who share their drug of choice, which may explain why religions are liable to proscribe certain drugs — as much to keep the flock loyal as for pharmacological reasons. (One downside of the decline in tobacco smoking is that at a party I can no longer instantly identify “my tribe” in a room full of strangers.)

That clustering matters. If three of your ten closest friends use a drug, it’s an optional extra; if eight of them do, it’s a social norm. This once was the case with tobacco. As a man in the 1950s, it took a certain level of stubborn determination to be a non-smoker, maybe as much as it takes to be an unrepentant smoker today. Perhaps the biggest benefit to one person quitting smoking is that their friends are now less likely to smoke. One reason I am not a stoner could be that although I have never been in a milieu that condemns it, I have never been in one that expects it either.

In Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, Mike is asked how he went bankrupt. “Two ways,” he replies. “Gradually, then suddenly.” This is how problems from drug liberalization will emerge, too. We seem to have reached a lazy, premature consensus that if early indications are favorable, the experiment should continue. Maybe. But maybe not.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply