However much it is denied, we still live in an imperial age, at least metaphorically. Just as the withdrawal from Afghanistan registers the momentary decline of the American empire, it registers the momentary rise of the Russian and Chinese ones. America failed in Afghanistan because its military, while capable of fighting high-tech wars on land and sea, could not fix complex Islamic societies on the ground. Indeed, Afghanistan demonstrated how the deterministic elements of geography, culture and ethnic and sectarian awareness can vanquish Western ideals of democracy and individual liberty.

It wasn’t nation-building per se that failed in Afghanistan; peaceful American and Soviet competition in bread-and-butter infrastructure development achieved much in Afghanistan in the mid-20th century. According to the Pakistani journalist Ahmed Rashid, it was America’s emphasis on — and obsession with — electoral processes at the expense of such infrastructure and agricultural development that helped doom it in the early 21st century.

This failure to appreciate the forces of culture and geography has geopolitical ramifications. America’s withdrawal from Afghanistan without stabilizing it may create a void that Russia and China will initially be hesitant to fill, hoping and assuming that when Afghanistan does stabilize somewhat under the Taliban they can proceed with using Afghanistan for natural-resource development (energy and mining), and for further connecting Central Asia in a land-and-sea network.

Compared to Russia and China, as well as Pakistan and India, which have concrete proximate interests in Afghanistan, America’s interests can, at least in the Biden administration’s estimation, be reduced to anti-terrorism, which it apparently believes it can do from over the horizon. Nevertheless, Central Asia is going to matter substantially in terms of 21st-century geopolitics.

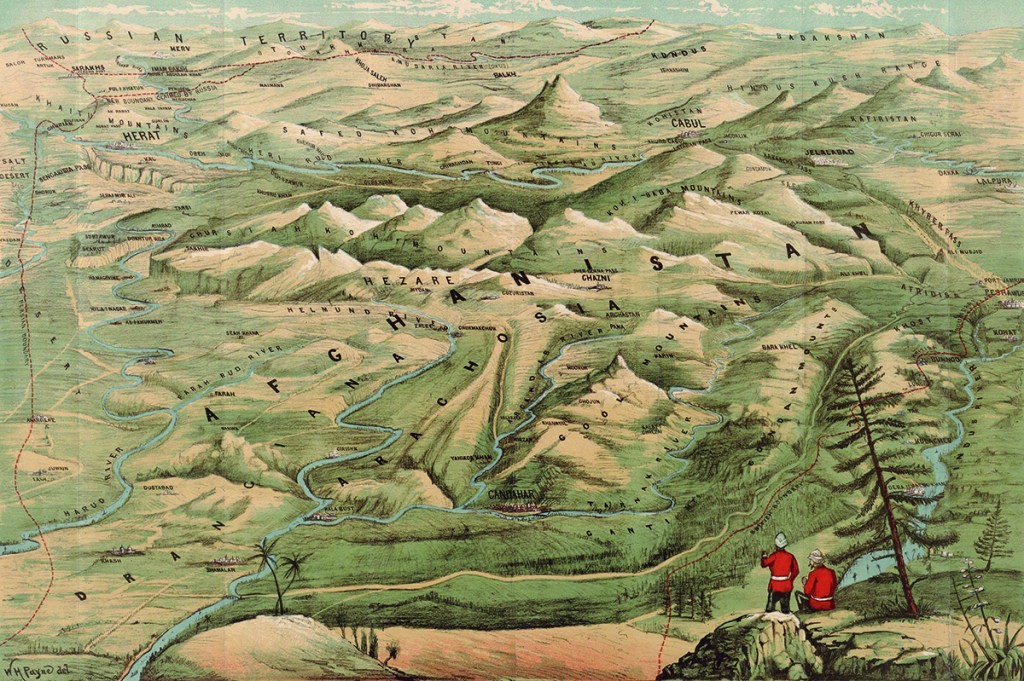

Halford Mackinder, the great British geographer of the early 20th century, vaguely foresaw both world wars when he proposed that, as the European imperial powers had staked out the habitable part of the earth by the end of the 19th century, they would henceforth have no further outlet for their energies except to fight each other. Mackinder also announced that with the development of railways crisscrossing the Eurasian landmass, control of the ‘Heartland’ of Eurasia would ultimately lead one of the great powers to dominate the Afro-Eurasian ‘World-Island’, that is, the eastern hemisphere. Mackinder’s idea was somewhat vague; the Heartland might have been interpreted to lie anywhere from Eastern Europe to Iran to Central Asia itself. His great insight was not so much identifying the interior of Eurasia as the geographical ‘pivot’ of history, but observing that the fight between Russia and Germany for control over the Eurasian interior had not been settled by World War One, and that their titanic struggle would go on — which it did, culminating in a second world war.

To assess 21st-century Central Asia we need to put Mackinder’s worldview together with the ‘Rimland’ thesis of the Dutch-American geopolitician Nicholas J. Spykman. The two are usually seen in opposition to each other: Mackinder identified the key to world power as the Eurasian interior; Spykman identified it as Eurasia’s navigable Rimland. The 44-year-long Cold War had both Mackinderesque and Spykmanesque qualities: the contested spaces — the Korean Peninsula, Vietnam, South Asia, Iran, Turkey, Greece and so on — all were located more or less on the Rimland of Eurasia, from the western Pacific to the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean.

America’s containment strategy was about keeping the Soviet Union, the great Heartland power, from advancing into the Rimland. The Soviets saw this as encirclement, and their 1979 invasion of Afghanistan, which began more than four decades of war there, was partly motivated by a desire to advance south toward the Indian Ocean, in order to break this encirclement. To be sure, Afghanistan constitutes a Heartland territory only 300 miles from the Indian Ocean Rimland. Still, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan notwithstanding, much of this remained in the realm of abstract geopolitical theorizing throughout the Cold War. But as we shall see, because of the advancement of transportation technology, Afghanistan’s geopolitical potential is about to mature and become increasingly obvious.

For the time being, this may be lost on the Biden administration. In fact, the last consciously geopolitically-minded American presidency was that of George H.W. Bush. The Cold War, as an extension of World War Two — as well as a worldwide competition between great military powers — concentrated the minds of many presidents of the era. In the post-Cold War period, ideals, values and ‘global’ issues have distracted attention from the geopolitical chessboard. But, consciously or not, the Biden team is, in fact, now operating geopolitically. And its playbook is that of Nicholas Spykman.

America’s Indo-Pacific strategy, designed to counter China, is very Spykmanesque. It concentrates on building up forces and relationships along the Eurasian Rimland from Japan south to Australia and then westward across the Indian Ocean to the Persian Gulf. By withdrawing from Afghanistan without sufficiently enunciating a diplomatic and security strategy for Central Asia, Biden’s team has chosen the Rimland over the Heartland. However, the Rimland and the Heartland are about to fuse in the coming years. Much will depend on Afghanistan.

With the American withdrawal, Afghanistan’s possibilities and its problems are about to affect the rest of Central Asia, whether through the refugees or terrorists streaming across its northern borders into the former Soviet republics of Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan or the pipelines that may be constructed to transport gas from Turkmenistan south through Afghanistan to the cities and Indian Ocean ports in Pakistan. At the same time, Central Asia is about to begin the process of becoming an organic whole, with Afghanistan, the former Soviet republics and China’s Xinjiang province (actually East Turkistan) increasingly influencing each other. Afghanistan may have been at war these past four decades, but the former Soviet republics, despite their artificiality in terms of borders and ethnic maps, have been, by and large, slowly congealing into credible states.

This greater Central Asia now forms the heart of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). For many centuries, with some exceptions, China was unable to go to sea in a substantial way because of the distraction caused by insecure land borders. But now that the borders are secure, China has the luxury to build a great navy. Seeking domination over the South China Sea and brutally repressing the Turkic Muslim Uighurs in Xinjiang are thus very much related: by pitilessly locking down Xinjiang and reaching out over its borders to the rest of Central Asia through BRI, China may finally have serenity in its most historically turbulent borderland.

In addition to striking west from Xinjiang across Central Asia to Iran and beyond, the BRI will proceed south from Xinjiang through Pakistan, to the Chinese-built port of Gwadar on the Indian Ocean (providing the Pakistani Taliban don’t disrupt it). This route may include spur lines into a postwar Afghanistan; meanwhile, the Indians and Iranians may build an energy and transport route from Iran’s Chabahar port on the Indian Ocean north through western Afghanistan to gas-rich Turkmenistan.

The more the Heartland and the Rimland are interconnected, and the more China’s BRI becomes regionally dominant, the greater the potential for China to dominate Mackinder’s World-Island, including Spykman’s Rimland. This is imperialism indeed, very mercantilist, and cartographically reminiscent of the Tang dynasty. The Chinese have been significantly increasing their security relationship with the Central Asian republics, in the form of military bases and the dispatch of war planes and drones, as well as bringing Central Asians to China for security-related training.

Of course, Russia will have a great say in all of this. Courtesy of the czarist and Soviet empires, Russian is still a lingua franca throughout much of Central Asia, where Russia’s military and security services are still ahead of China’s. Russia and China are officially strategic allies, but they obviously compete in Central Asia. Consequently, it should be American policy that no one outside power dominate Central Asia. For that to happen, the United States will have to remain active in Central Asia beyond simply monitoring Afghanistan-based terrorism from perches at sea and perhaps in the former Soviet republics. By active, I don’t mean via the insertion of troops, but through a robust and well-defined diplomatic and economic strategy. In effect, the United States needs to convey to the countries of Central Asia what secretary of state James Baker III did to Mongolia in 1990: think of us as your third neighbor, far away only geographically.

Indeed, as landlocked Central Asia becomes more connected to the Indian Ocean through transport routes and pipelines, American soft power will be necessary to shore up the Indo-Pacific. Otherwise — unless Russia can check the Belt and Road Initiative, which is questionable — China could be on its way to commanding the World-Island. Remember that the United States won World War Two and the Cold War because no one power dominated Eurasia, so that the geopolitical and economic heft provided by the resource-rich temperate zone of North America was enough to tip the balance first against Nazi Germany and later against the Soviet Union. China must never dominate the World-Island the way the United States has geopolitically dominated the western hemisphere.

Meanwhile, neither China nor Russia nor anyone else is rushing into post-American Afghanistan. At least in the short run, it will be in the interest of Russia, itself nervous about Islamic terrorism, not to hinder the United States from monitoring extremist groups in Afghanistan. China’s attitude for the moment is similar, warning as it is of disorder in Afghanistan. A geopolitical waiting game will now ensue to see if the Taliban can actually govern. Only then can the future I outline here commence.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2021 World edition.