Last month the New Yorker published an essay about a grotesque experiment that took place in West Germany in the 1970s, in which young boys who had been taken from, or abandoned by, their parents were placed with known pedophiles.

It was no accident. It was quite deliberate. The powerful sexologist Helmet Kentler believed that pedophilic guardianship would foster an open and unashamed attitude towards sex that would preclude the development of fascistic attitudes. As the New Yorker says:

’Kentler’s goal was to develop a child-rearing philosophy for a new kind of German man. Sexual liberation, he wrote, was the best way to “prevent another Auschwitz.”’

A sensible reader could guess what happened to the boys. Those that the New Yorker spoke to report feeling depression and rage deep into adulthood.

Kentler was appalling, but he was of his time. Taboos surrounding children were being eroded. The German Green party was especially notable for its enablement of child abuse. As the Times of London reported in 2015, ‘a paedophile network was active in the Berlin branch of the Green party until the mid-1990s, with potentially hundreds of victims’.

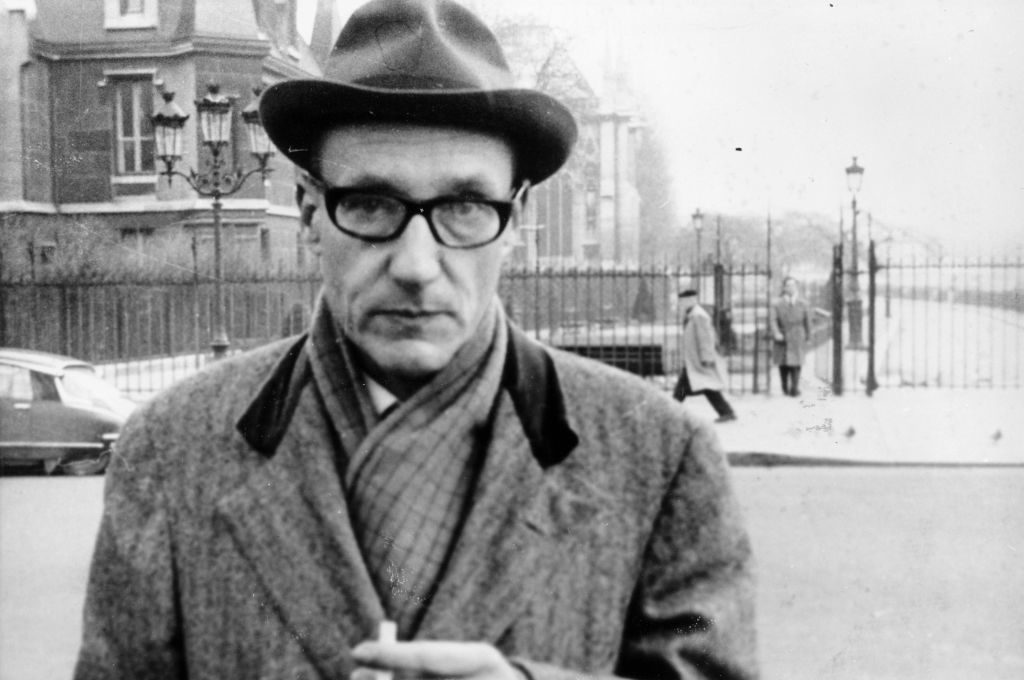

Daniel Cohn-Bendit, a leading student activist in the 1968 unrest and a prominent member of the Greens, wrote fantasies about sexual contact with children which he later awkwardly described as ‘irresponsible’ and ‘a type of manifesto against the bourgeois society’. Cohn-Bendit was not, as you might assume, a harebrained student when he wrote that filth but 30 years old. Perhaps the bourgeois society had something — at least something — to be said for it.

You could attempt to ascribe all of this to post-war German pathologies — except that enthusiasm for the potential of childhood sexuality was common throughout the counter-cultural movements of the Sixties and Seventies. It may not have been a cause to rival the campaign against the war in Vietnam but it was a major one, with powerful friends.

Some cultural figures were very much self-interested. The French author Gabriel Matzneff wrote about raping children for years before it turned out that he was, of all things, a child rapist. It took the publication of Vanessa Springora’s memoir Consent, in 2020, in which she related being abused by Matzneff, for him to face repercussions. Being able to turn a sentence, it appears, is a good way of dodging a sentence. Your crimes are attributed to artistic license.

Others were driven by ideology. French intellectuals were especially energetic in their efforts to normalize pedophilia. A who’s-who of Gallic literary figures signed a petition in 1977 that called for sex between adults and children to be decriminalized, including Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir.

Foucault helpfully clarified that when he said children he meant children. In a radio conversation in 1978 he dismissed the very concept of being underage:

‘An age barrier laid down by law does not have much sense. Again, the child may be trusted to say whether or not he was subjected to violence.’

Any child who is able to express themselves, he was explicitly suggesting, is able to ‘consent’ — as if an eight-year-old and an 18-year-old have the same psychological capacity. The generous explanation of such a belief is arrant foolishness. The alternative is criminal opportunism.

But amid enthusiasm for women’s liberation, gay liberation and the sexual revolution, it was tempting for progressives to assume that kids had been constrained by the repressive systems they believed had been confining them. Allen Ginsberg, author of the poem ‘Howl’, joined NAMBLA, the North American Man/Boy Love Association. Reportedly, Ginsberg said, ‘I’m a member of NAMBLA because I love boys too — everybody does, who has a little humanity.’ This seems a bit like saying that you are a national socialist because you like your nation and you’re very sociable.

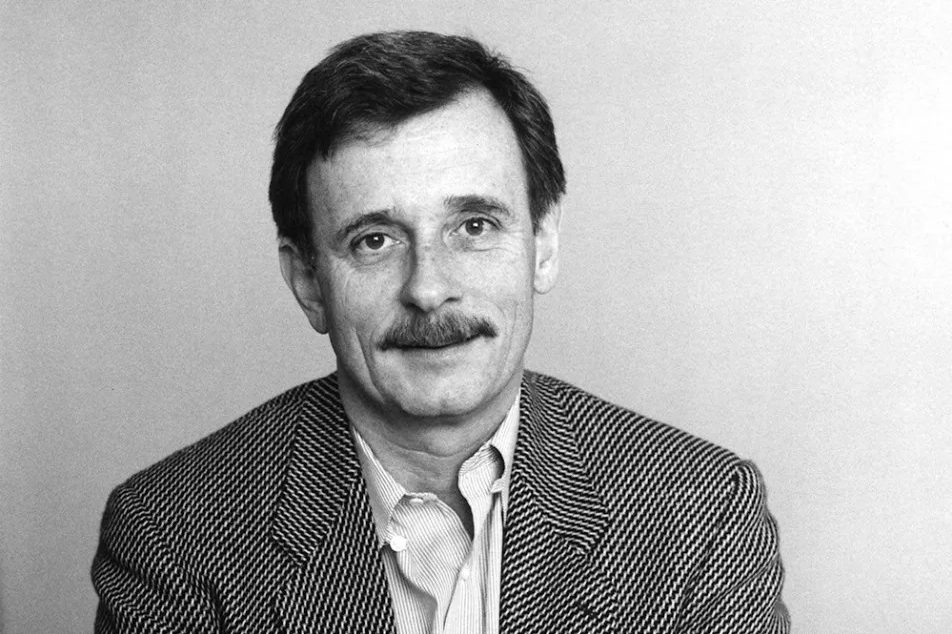

In correspondence with Ginsberg, William Burroughs, author of The Naked Lunch, reported paying two Arabic boys to have sex with one another. Burroughs’s biographer Barry Miles claimed that Burroughs used this anecdote in The Naked Lunch ‘to purposely annoy his readers, a Swiftian gesture to reveal their prurience and to undermine their middle-class values’. It would seem more ‘Swiftian’ if Swift had actually eaten Irish kids.

Of course, all of these efforts failed. Pedophilia, thankfully, was a bridge too far for the general public — who had grown increasingly receptive to individual choice but who were not convinced by the idea that this principle could be extended to kids, or that strange, sweaty men talking about ‘man/boy love’ had any interest in the kids’ wellbeing.

Still, this dark phenomenon endures in relevance. We often hear about being on the ‘right side of history’, as if there is a natural drift of civilized societies towards a more enlightened state of being, associated, typically, with the discarding of taboos and the acceptance of new and innovative social standards. Sometimes a taboo should be discarded. But sometimes they have a damn good reason to exist and people should not feel narrow-minded or parochial for opposing change. You see, for example, the same exaggeration of childhood agency as a means of enabling exploitation in cases of so-called ‘drag kids’.

Sometimes, too, as this case reminds us, change is not inevitable and can be reversed. Foucault is still respected on the strength of other aspects of his work, but if he was demanding the end of age of consent laws nowadays he would lose his intellectual respectability before you could say ‘structuralism’.

Note: an earlier version of this article referred to claims about Michel Foucault that are less credible than those about the other people mentioned.