Was China involved in the coup in Myanmar? It seems unlikely, but that does not mean Beijing is blameless.

As satisfying as it might be to point the finger at an omnipotent and scheming superpower, the reality is rather more complicated. After all, for all the shenanigans associated with China’s wolf-warrior diplomacy, Beijing is not as reckless or revisionist in its ambitions as it was back in the mid- to late 60s.

Back then, amid the chaos of the cultural revolution, Mao set about spreading his revolutionary thought abroad. Myanmar was firmly in his sights.

In Southeast Asia, Beijing supplied communist guerrillas with money, weapons and training in an effort to instigate civil wars. In Myanmar, the ethnic-Chinese minority was also mobilized. On the streets of Yangon, they wore with pride badges of the Great Helmsman and brandished copies of the Little Red Book. The result was bloodshed. Not that this bothered Mao; he believed his country was leading a righteous Third World front against American imperialism and Soviet revisionism. Even if it was a rather lonely crusade.

It is worth remembering this disastrous period in China’s history because it contrasts with today. Beijing is no longer a proselytizer trying to violently export communist doctrine. Yet as Myanmar’s recent history shows, Beijing still threatens efforts to promote liberal democratic values worldwide. It’s just the communist party’s methods now are much subtler than starting coups.

In Myanmar, it is likely that the military acted on its own accord. Frustrated by their weakened (albeit still tight) grip on power during the early years of democratization, they used the results of last year’s elections, which Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy won comfortably, as an opportunity to scream foul and re-take full control.

The fact Myanmar’s top general, now leader, Min Aung Hlaing raised complaints about election fraud with China’s foreign minister Wang Yi during a meeting last month does not necessarily point to a shadowy conspiracy. In fact, there are many reasons to believe that China would not want a coup.

Above all else, China wants stability to prevent turmoil spilling over its southern border. It also seeks to protect its investments in Myanmar and access to the country’s plentiful natural resources, which were already guaranteed under the leadership of Suu Kyi.

Although events in Hong Kong have shown that the Chinese government is a dictatorship with an utter contempt for democracy, when choosing international partners, the Chinese Communist party is far more pragmatic. It doesn’t matter whether a leader is a democrat or tyrant, to alter an expression of Deng Xiaoping’s, as long as they buy into Belt and Road.

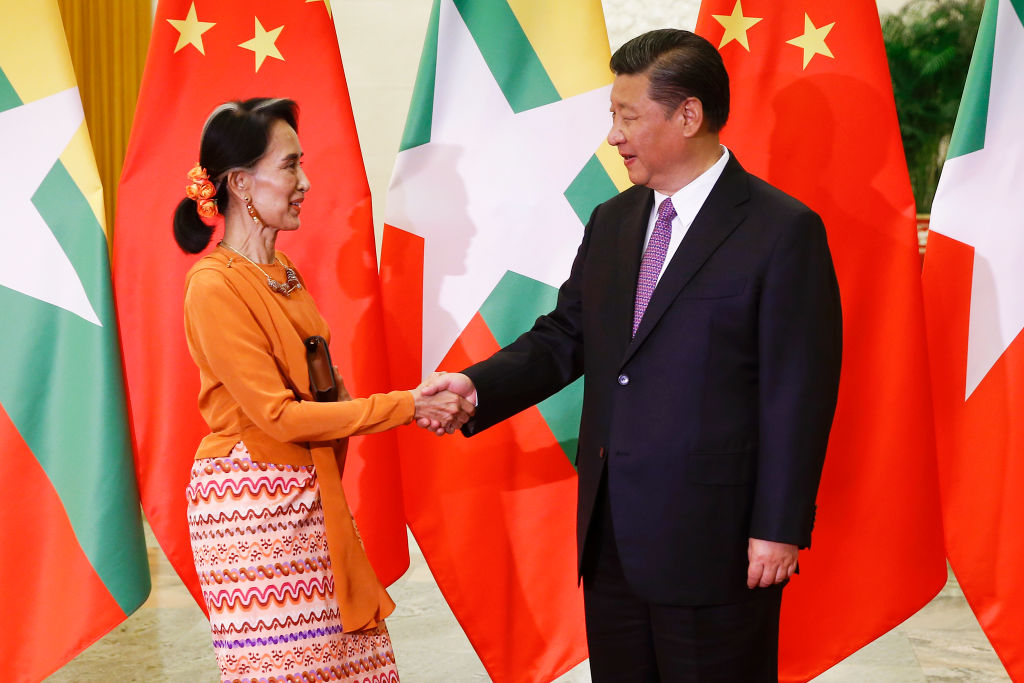

Only last year, Xi Jinping visited Myanmar, signing dozens of infrastructure deals and promising to support the country’s development. Over the past few years, both countries had entered to into a quid pro quo relationship inside international human rights bodies which involved shielding each other from criticism. Myanmar was already firmly in Beijing’s orbit.

Let’s remember too that Myanmar’s military takes orders from no one. Like most players in the region, they are weary of their bigger neighbor to the north. Their slight relinquishing of power 10 years ago is thought by some to have been driven by a desire to reduced dependency on China in order to attract investment from the West. Allegations that Beijing funds and arms ethnic militias in Myanmar’s north only fuels further distrust.

But there is a but: it is impossible to imagine the military making such a reckless move if they had not been confident of Beijing’s protection from the criticism and, more importantly, to sanctions which are likely to come from the West. It would be a shrewd bet given China’s previous support for military rule in Myanmar when the rest of the world regarded the country as an international pariah. What’s more, Beijing’s self-avowed policy of ‘non-interference’ in other country’s internal affairs is an open invitation for any strongman or junta to behave badly.

Whether General Hlaing had received tacit support or made a gamble in the dark, the military’s move seems, so far, to have paid off. Chinese state-media has already attempted to legitimize the move by referring to the coup as a ‘major cabinet reshuffle’. China, along with Russia, has also stalled efforts at the United Nations Security Council to issue a statement condemning the coup.

While the new Biden administration has threatened to re-impose sanctions which had previously been lifted as the country moved towards democracy, their effectiveness will be thwarted by Beijing’s business-as-usual approach.

The Chinese Communist party is no longer violently exporting its ideology abroad, yet its effect on democracy worldwide is still dangerous. No, China probably wasn’t directly involved in this week’s coup. But if, thanks to Beijing’s ‘non-interference’, the Myanmar military demonstrate seizing power in this way is largely cost-free, what’s to stop others following in their footsteps?

Gray Sergeant is a research fellow in the Asia Studies Centre at the Henry Jackson Society. This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.