This article is in The Spectator’s February 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.

‘Cancel culture’ is a horrible term because outside of a dictatorship nobody can actually be ‘canceled’ or otherwise ‘disappeared’. All that can happen is that people can be found to have trodden across one of the orthodoxies of the age. A small number of bullies then come for them. And a larger number of otherwise decent people then fail to stand up for them. It is it this last part of the matter that is worth focusing on. It is the only part that is fixable.

All ages have their orthodoxies. And if writers, artists, thinkers and comedians do not occasionally tread on them, then they are not doing their jobs. Meanwhile human nature remains what it is. And just as some children will always pull the wings off flies and fry small ants with their toy magnifying glasses, so a certain number of adult inadequates will find meaning in their lives by sniffing around the seats in the public square until they find an aroma they can claim offends them.

Which brings us back to the fixable matter: the wider cowardice, the societal silence. When Evergreen State College turned hooligan in 2017, the shock was not that American universities contained students unsuited to any education outside a correctional facility. Nor, frankly, was it a surprise that the college president — George Bridges — was so supine that he ended up begging the student protesters to allow him to go to the bathroom to pee (‘Hold it’ was the advice given by one hoodlum). What was surprising was that even when the professor who had inadvertently caused the breakdown (leftwing, Bernie-supporting, lifetime Democrat Bret Weinstein) was physically threatened, repeatedly defamed and finally chased off campus for good, not one of his longstanding colleagues took any public stance in his defense. Solidarity — perhaps the noblest aspiration of the political left — was totally absent. And these academics and administrators were not living in 1930s Moscow, but in 21st-century Washington State.

In case after case it has been the same. The problem is not that the sacrificial victim is selected. The problem is that the people who destroy his reputation are permitted to do so by the complicity, silence and slinking away of everybody else.

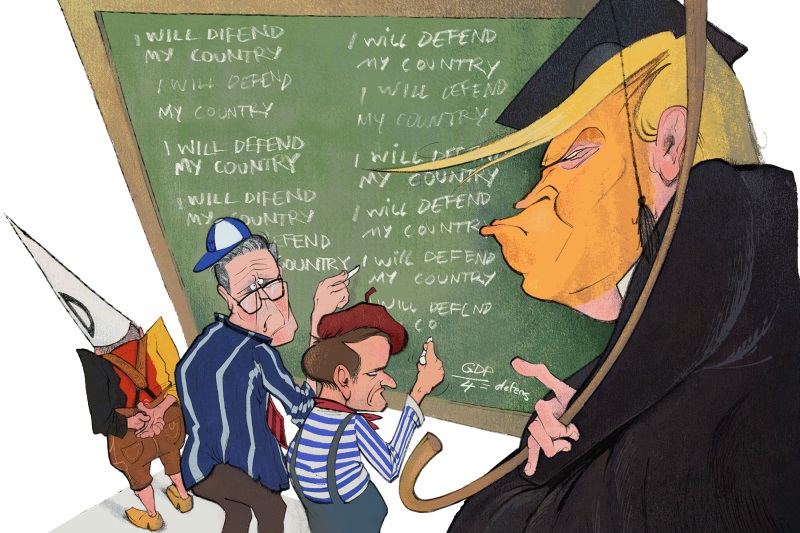

So here is an idea. How about we start to encourage the return of what Susan Sontag once (unusually memorably) called ‘a little civic fortitude’? That we encourage people to stand up in defense of people who are being defamed? It has been suggested before. Last year after Jordan Peterson and the late Roger Scruton suffered attempted bulldozings in quick succession, Niall Ferguson wrote in the Sunday Times of London that perhaps public intellectuals and academics in the West ought to develop some policy like Nato’s Article 5: that is, a ‘one for all, all for one’ policy. The only problem with which — as Ferguson conceded — is that it is not as clear as it is with Nato who is in and who is out. In the intellectual Nato, who is France and who is Ukraine? Who are the Baltic states and who is Georgia?

So here is my own reduced solution. Simply stand up for your friends, colleagues or allies when you know that they are being lied about. It seems so simple and so obvious a thing to do, and yet it is a habit in exceptionally short supply in America today.

When that semiliterate mob claimed Bret Weinstein was a racist, why did his and his wife’s colleagues not stand up and say, ‘Hang on a second. I’ve known these people for decades. You come for the Weinsteins, you come for me.’ Or even just, ‘I happen to know they are not racists, so take that back.’

When Nicholas Christakis was surrounded by a screaming mob of Yale students we could have expected that Yale would be so avaricious and weak that it wouldn’t expel each of those students that very evening. But why did Christakis’s colleagues not rise up that night en masse to say, ‘Excuse me, but however much money they are paying, students should not be allowed to threaten, insult and intimidate academics’? Why is it that in so many areas of public life, from the lecture hall to the comedy club, when the mini-mob comes, the adults just vacate the room?

One mistake that the political center and right can make as easily as the political left is to hope that all large problems will eventually be solved by government intervention or diktat. Yet the conundrum at hand requires no such thing, and to expect it or hope for it is an example of the free-speech defender in lazy repose: covered in nacho crumbs, remote control in hand, vaguely waiting for the cavalry to arrive.

Well, in my experience, the cavalry never does arrive. Or rather, the lesson of middle age is the at-first frightening, then hilarious, and finally shrugging acceptance that the cavalry is you.

Of course we will all worry constantly about whose side we should ride to. I watched with a degree of awe last year when Jordan Peterson tried to give Milo Yiannopoulos a leg back up by having a discussion with him on YouTube. Not that Yiannopoulos had been gracious or kind about Peterson in the past. But Peterson realized there was something sinister and wrong about someone being chased off every publishing platform if he was not breaking any laws.

Still, it is a fine calculation. On the occasions when I have gone in to try to drag someone away from the mob I have done it mainly for people I know, trust, admire and love. ‘You are not getting them’ is the instinct that fires me. When I have managed to do it, as I did last year for Roger Scruton, it worked at least in part because fighting for something you love will always give you an advantage over someone fighting because of hate.

There is a happy by-product of this, by the way: when you fight to defend your friends, you let them know something that you might otherwise forget to tell them. A minor by-product of the fight — but a major consolation in the long run of life.

This article is in The Spectator’s February 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.