What would happen if Americans voted on different days? Suppose Republicans voted on Tuesday and Democrats voted on Wednesday. Would this be better than everyone voting on the same day? Would it be more fair and less confusing?

Like hell it would! One reasonable complaint Republicans had about the 2000 presidential elections — famously decided, in the end, at the Supreme Court — was that some television networks called the State of Florida for Al Gore before polls had closed in the westernmost Florida Panhandle, which lay in the Central Time Zone, an hour behind the rest of the state in the Eastern Time Zone. Declaring a winner prematurely amounted to telling Panhandle voters not to bother casting their ballots. And considering how close Florida was in the end, that could have made a difference to the outcome.

Now, the year of the coronavirus, Democrats want to maximize the amount of voting by mail throughout the country. This promises to be the trigger of an even worse voting-process breakdown than the one that occurred in 2000: it increases the risk of lost ballots, dubiously ‘found’ ballots and spoiled or improperly completed ballots whose validity will be subject to interpretation — like the infamous ‘hanging chads’ in the 2000 election.

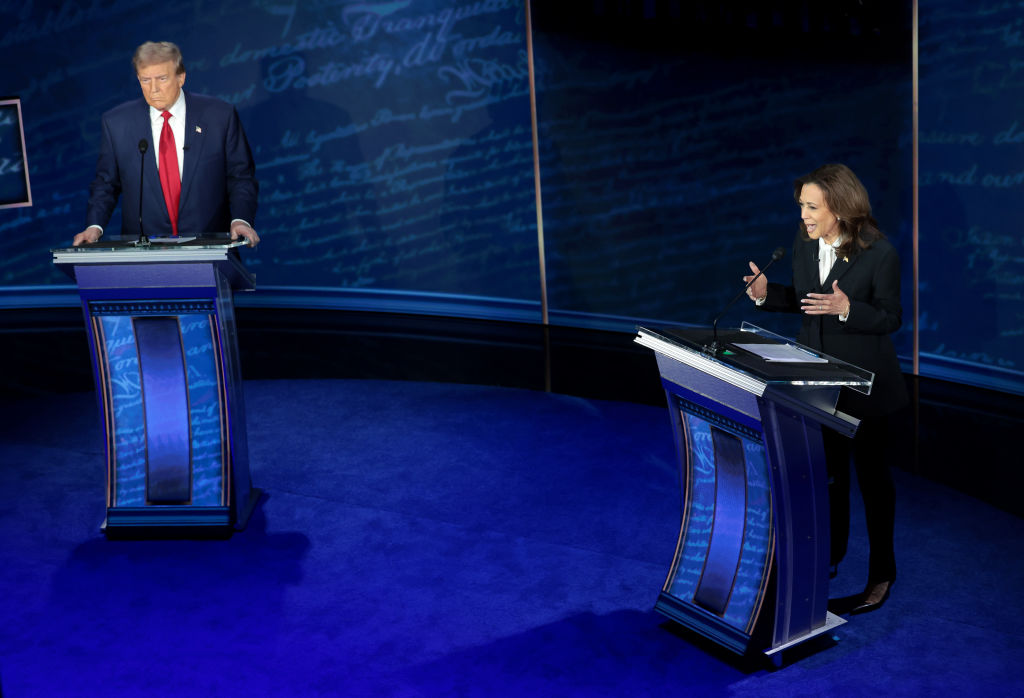

There are two even more fundamental problems with the push for mail-in voting: it violates the very principle and concept of an election in the way most Americans have understood it until now, as something that happens at a particular place and time. And it creates, in effect, different elections and different electorates for Donald Trump and Joe Biden, one of which might win the day-of voting while the other wins the mail-in vote. When different principles are combined with different outcomes, it’s a recipe for a legitimacy crisis, even if the ensuing litigation doesn’t lead, once again, to the final decision being made by a Republican majority on the Supreme Court.

Democracy is in danger, but the threat is not coming from Donald Trump. Ever since he started winning Republican primaries four years ago, Trump has been painted by Democrats and liberals in the media as a mad authoritarian who might just wreck democracy itself. This portrait has been hypocritical in the extreme from the very first. Trump is said, for example, to be a threat to democracy because he doesn’t spend enough words morally denouncing Kim Jong-un or Rodrigo Duterte. Yet the same self-appointed watchdogs of democracy had nothing bad to say when Barack Obama made more than friendly overtures to the Islamist regime in Tehran or the still thoroughly undemocratic government of Cuba. Trump is said to be a puppet of Vladimir Putin, yet Nato has expanded under Trump’s administration, and the President’s relocation of some American forces from Germany to Poland is not exactly pulling away from what liberals evidently perceive as the Russian front.

Trump has won all his elections here at home fairly and constitutionally, and voters had no trouble democratically rebuking the President’s party in the 2018 midterms. The scuffles that erupted at a handful of Trump rallies four years ago were denounced as an unprecedented intrusion of violence into American politics by many pundits who later described rioting and arson in Democrat-run cities this year as ‘mostly peaceful protests’.

No exposure of his own hypocrisy can prick the conscience of the Trump-maddened liberal, however. In an electoral war-game exercise in which John Podesta played the part of Joe Biden this August, the Democratic side refused to concede the 2020 election if it were won by Trump. And Hillary Clinton herself didn’t concede on the night she lost — she postponed her concession until the next day. Yet Democrats and their allies persist in floating scenarios in which it is President Trump who tries to defy the judgment of the voters this November.

The effect of this media campaign is to pre-establish an anti-Trump narrative if something like the 2000 election’s Bush-Gore deadlock happens again. One of the great lessons for American democracy over the past several years, for those paying attention, has been the way in which a master narrative can be established to control American politics even when the facts — about Russian collusion, for example, and Moscow hookers frolicking with the future president — never turn up.

A week after the Republican convention in the summer, another such narrative sprang up, this one involving anonymously sourced and anonymously ‘confirmed’ claims that the President had insulted the memory of American troops who died in World War One. Was it a coincidence that after the Democratic convention and a tie-in publicity campaign highlighting ex-Republican national security officials who were now backing Biden, the editor of the Atlantic happened to wake up one morning with the idea of getting anonymous sources to tell him about an incident that supposedly took place in France two years ago? The Atlantic’s owner, Laurene Powell Jobs, was listed only as one of ‘Biden’s biggest benefactors’ in the previous quarter by the New York Times, ‘among those who gave at least $500,000’ — not that her contribution to the Democratic effort can be measured by mere dollars.

Progressives are not unaware of what’s in store with mail-in voting. An Emerson College poll conducted at the end of August only confirmed what the politically savvy already knew: that different candidates will not fare the same when different voting methods are used. According to Emerson, ‘Voters planning to vote early in person are breaking for Trump 50 percent to 49 percent while those who plan to vote in person on election break for the President 57 percent to 37 percent. Voters who said they plan to vote by mail break for Biden 67 percent to 28 percent.’

A term has even been coined for the advantage Democrats tend to get from non-traditional voting: blue shift. ‘The counting of votes in contemporary American elections is usually not completed on Election Night. There has been an increasing tendency for vote shares to shift toward Democratic candidates after Election Day in general elections,’ write the political scientists Yimeng Li, Michelle Hyun and R. Michael Alvarez of the California Institute of Technology.

A multitude of things can go wrong with postal ballots (forgotten signatures, late delivery or bags of mail turning up unexpectedly, for starters), setting the stage for a candidate who wins by mail but loses among voters on Election Day to mount a challenge — or rather, to mount challenge after challenge, state by state, anywhere the day-of winner’s margin might be close enough to overcome. As Americans learned 20 years ago in Florida’s presidential vote-counting and recounting, even without mail-in voting much can go amiss. Now consider what would have happened if the Florida recount had taken place with masses of postal ballots in the mix too. And then imagine the Florida scenario playing out in Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, Arizona and God knows where else.

It’s an ugly picture. The more ugliness there is — the more states with contested ballots that could override the results of the uncontested votes — the likelier the whole thing is to wind up in front of the Supreme Court, as it did 20 years ago. Are Democrats prepared to accept a second justice-decided election that goes against them? Will the Republican-majority Court, fearful of again seeming partisan, in fact show a bias toward Biden? Republicans may well think so if a decision goes against them. Justice John Roberts’s record so far does nothing to allay suspicions that he makes such political calculations to preserve the court’s appearance of ‘balance’. But if the court has to decide a presidential election once again, it will suffer grave damage to its reputation no matter what. As may the entire electoral system.

Therein lies a greater problem. Sore losers are nothing new in American politics, and even an absolutely clear win by Trump or Biden will leave many voters angry and heartbroken and even in denial about the result. A revolution in the very idea of what an election is, however, leads to a new and deeper kind of conflict. Already progressives have fantasized about abolishing the Electoral College and ending the equal representation of states in the Senate. In Maine, progressives have instituted a new ranked-choice voting system. Armed with the precedent of this November’s election, under the favorable conditions imposed by the COVID-19 crisis, expansion of mail-in voting may be next. Five states — Democratic-leaning Washington, Oregon and Hawaii, semi-battleground Colorado and Republican-leaning Utah — presently conduct their elections entirely by mail. The coronavirus situation has led other states to loosen requirements for absentee voting and widen opportunities for non-absentee postal voting.

Oregon was the first state to adopt all-postal voting, after a 1998 referendum. Others have followed suit only in the past decade. The implications of further movement in this direction are revolutionary for the very idea of democracy: instead of an election taking place in a specific location on a specific day, an election becomes more of a virtual event. Although votes may still be registered to particular districts, voters can mail in their votes from anywhere. And they can do so at any time within an extended period of weeks or months. Within that time, news may break, voters may die, candidates themselves may die or drop out of the race, yet ballots will be cast long before the race has reached its end. The election ceases to be an election in the traditional sense and becomes an ongoing survey of public opinion.

In a moment of decision on Election Day, when the whole district or whole country is making a choice at once, a voter in the balloting booth is free from the influence of outside opinion: no campaigning is allowed inside the polling place, no television blaring out news with a partisan slant. No one else is present to pressure the voter psychologically — or physically — into checking the right box. None of these protections for conscience apply, or apply effectively, to mail-in voting. Voters are subjected to greater manipulation by the media and their social environment. And the psychological state of the voter is different: it’s easier to make a bold decision in a moment of great consequence than it is to hold fast to a defiant conviction over an extended period. As is so often the case with progressive liberalism, the system breeds conformity.

In fact, mail-in votes invert the purpose of elections as formerly understood: instead of giving the public a sharp choice, virtualized voting becomes a means for securing passive assent to whatever those who know best have already decided. The drift was underway even before COVID-19 created conditions favorable for a mail-in voting push. Requirements for early voting and absentee voting have been getting looser and looser cycle by cycle. But now the opportunity to end elections as we know them is upon the horizon. Before that happens, though, there may be a backlash from voters who understand what is happening — that unmanaged democracy, real democracy, is dying in broad daylight.

This article is in The Spectator’s October 2020 US edition.