This article is in The Spectator’s January 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.

‘Great nations do not fight endless wars,’ President Donald Trump declared in his 2019 State of the Union address. Simultaneously benign and radically subversive, this simple statement may well qualify as an important moment in the Trump era. Here was a notably dishonest president calling attention to a truth that the political establishment appears intent on ignoring. Any objective look at the record of US military actions since 9/11 would reach similar conclusions. The politicians ordaining our wars have been reckless and incompetent. The soldiers sent to fight are brave but badly misused. And the people in whose name these wars are waged are oblivious to what has occurred.

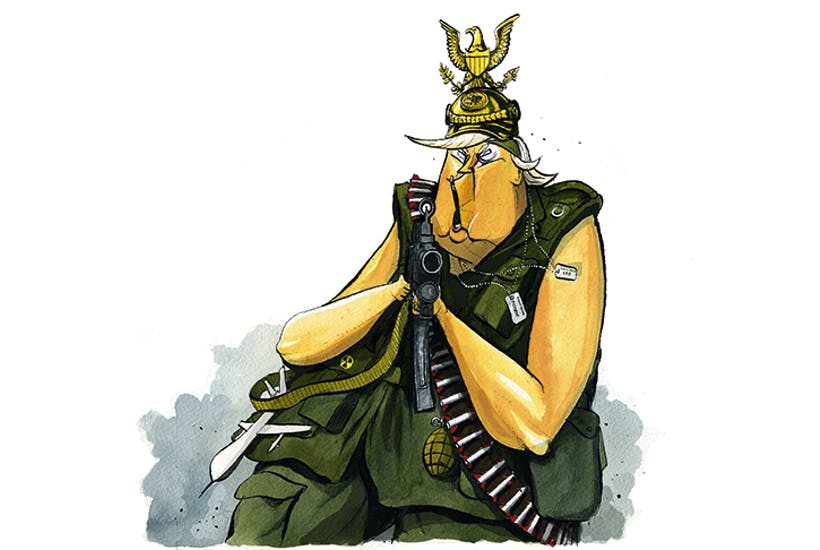

What accounts for the nation’s perverse infatuation with all things military? First, hawkishness tends to play well with voters. Second, the national security apparatus — in contemporary parlance, the ‘deep state’ — guards its prerogatives by perpetuating a sense of alarm. Specific threats come and go but, we are told, existential dangers are constant. Third, the military-industrial complex and its enablers in Congress, the media and think tanks: all that money suppresses critical questioning. Fourth, a tendentious reading of history in which any backsliding from militarized globalism leads inevitably to isolationism and then totalitarianism, appeasement and genocide. Fifth, the abandonment of fiscal responsibility. If, as Dick Cheney said, ‘deficits don’t matter’, then incentives to scrutinize the Pentagon’s vast expenditures disappear, even if US military spending exceeds by orders of magnitude that of any plausible adversary.

Finally, there is the crushing power of inertia and the hardening of policy contours established decades ago: all those alliances, foreign bases, four-star headquarters, sprawling bureaucracies and baked-in redundancies, not to mention the recurring conferences, exercises and reports. This is how the US military does business. Doing next year what we did last year and the year before is comforting, and it obviates any need to think.

The militaristic cast of American policy derives from interconnected, mutually reinforcing sources. Hence its durability despite the manifest failures it produces. Washington’s militarized mindset is impervious to the challenge of events. Take the epic catastrophe of the Iraq War. Apart from hastening the introduction of a few bits of military gadgetry, the war had no perceptible impact on policy-making. One step remains to expunge it from memory altogether: erecting a memorial somewhere near the Mall in Washington. That will allow ‘the Blob’ to forget the Iraq debacle entirely.

There are always a gallant few naysayers: institutions and individuals who challenge the national security status quo by denouncing brain-dead policies, needless interventions, cost overruns and path dependency. Those efforts are honorable. Yet the results achieved since 1947, when the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists created the ‘Doomsday Clock’, show that the dissenters have barely dented how Washington thinks and acts. Within the Beltway, almost no one pays attention to the Doomsday Clock or dissent.

Why have the anti-militarists’ valiant efforts to promote a more peaceful approach yielded so little? After the Vietnam War, the American people generally opted out. They have deferred to establishment elites, and this has given those elites and especially the Commander in Chief a free hand to wage endless wars endlessly.

The foreign-policy establishment will persist in its misguided policies until the American people demand a different course. And the people will demand a different course only when they experience firsthand the consequences of misguided policies. Ending the public’s insulation from the costs of war is a prerequisite to ending the wars themselves.

The core issue is the system by which the state converts human resources into military capabilities. We have a perniciously misleading name for that system: the All-Volunteer Force (AVF). As the basis of our military system, the AVF underwrites American militarism and affirms that the people as such need play no role in defending the nation. The AVF makes endless war possible.

Here a brief digression into military history may be in order. Until recently, the foundation of the American military system was the citizen-soldier who rallied to the colors in time of need. This approach prevailed from Lexington and Concord in 1775 through to Vietnam, after which it collapsed. The Founders saw little need and had less regard for what they called a ‘standing army’, which, as Sam Adams put it in 1776, is ‘always dangerous to the Liberties of the People’.

To be sure, regulars were not without value. During the Revolutionary War, George Washington’s Continentals, a nascent regular army, contributed mightily to the winning of independence, although Washington supplemented his ranks with less reliable local militias. During the 19th century, bluecoated regulars facilitated westward expansion by pacifying Native Americans. In the first decades of the 20th century, the regulars policed outposts of the American empire in China, the Philippines and the Caribbean.

Even so, in every major conflict from the War of 1812 to Korea, citizen-soldiers rather than regulars did the preponderance of the fighting and dying. At my alma mater, West Point, an imposing shaft of polished granite honors the sacrifice of regulars, both officers and men, who lost their lives in the Civil War. Inscribed on Battle Monument are 2,230 names, a not-insignificant number. Yet it is only a fraction of the 13,942 volunteers from my current home state of Massachusetts who died in that war. It was citizen-soldiers, rather than regulars, who saved the Union.

From the founding of the Republic to the Vietnam War, national defense was a collective responsibility inherent in citizenship. Indeed, those denied full citizenship, such as African Americans and women, were either excluded from military service or permitted to play only an auxiliary role. As a consequence of Vietnam, however, all that changed. By ending the draft in 1973, President Richard Nixon ratified a decision already made by military-age Americans to deep-six the citizen-soldier tradition. Terminating conscription redefined the concept of citizenship, which henceforth de-emphasized obligations in favor of privileges.

The new post-Vietnam military system yielded myriad effects, some anticipated, others not. Military service now became entirely a matter of choice, devoid of civic or moral implications. The need to widen the pool of potential volunteers expanded opportunities for people of color, women and eventually gays. Discipline within each of the armed services improved, with first sergeants and chief petty officers happily endorsing the results. Would-be volunteers found themselves in a better bargaining position, which translated into the generous financial inducements to enlist and to reenlist without which the AVF would collapse in a matter of months. For a kid fresh out of high school in postindustrial America, few things could match military service when it came to salary, benefits and the possibility of a lifelong pension.

What’s not to like? Several things, as it transpires. First, if victory means achieving intended political objectives expeditiously and economically, the post-9/11 US military doesn’t win. Second, when post-9/11 contingencies have exceeded the AVF’s capacity to put ‘boots on the ground’, the United States has found itself with too much war and too few warriors. Efforts to plug the gap by turning to reserves, allies or private contractors have proved of limited value — as has substituting technology such as missile-firing drones for actual soldiers. With dialing up a few thousand additional conscripts no longer an option, expanding a professional military turns out to be very difficult and very expensive.

Third, and most importantly, as the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have dragged on and on, the public has lost interest and simply tuned out. Americans do ‘support the troops’, of that there can be no doubt. For assurance, we need only watch footage of President Trump’s notorious July 4 celebration of America’s military might or tune into the festivities preceding a major athletic event and hear how the fans cheer any mention of those who serve. Were that not enough, the troops may also qualify for a 10 percent discount at certain big-box stores and, if in uniform, be invited to board commercial airliners right after the passengers in first class.

Support of this type, though, is almost entirely devoid of substantive meaning. In a real sense, the American people today have abandoned the troops, exempting themselves from knowing what the troops are doing where and at what cost. When it comes to war, American citizens have gone AWOL, choosing to become mere spectators. They allow authorities in Washington to do as they will with the troops. The AVF underwrites American militarism by allowing and even encouraging this. Here, I submit, is the ultimate explanation for the persistence of endless war.

Are there alternatives to the AVF? Of course there are, just as there are alternatives to prevailing American practices of gun ownership or healthcare. One obvious alternative is to restore the tradition of the citizen-soldier as it was devised by the Founders, albeit in ways suitable to 21st-century conditions.

Rather than revive the 20th-century reliance on conscription, it would be far preferable to institute a mandatory program of national service through which all young people would devote a period of service to their country or community. Some might join the military. Depending on the needs of the moment, most would probably make their contribution elsewhere. But all would serve in one way or another. This common experience would confirm that citizenship entails obligations as well as privileges.

In his farewell address, President Dwight D. Eisenhower insisted on the necessity of an ‘alert and knowledgeable citizenry’ keeping a watchful eye on the military-industrial complex so that ‘security and liberty may prosper together’. A program of national service, supplanting the AVF as the cornerstone of the military system, offers a practical way of nurturing citizens who are alert, knowledgeable and engaged.

Abolishing the AVF in favor of reviving the citizen-soldier tradition would not in itself end our endless wars, any more than capping carbon emissions will solve the problem of climate change. Yet unless the planet finds a way to cap carbon emissions, then anthropogenic climate change will likely continue unchecked. Similarly, the habit of endless war will persist unless the United States rids itself of the All-Volunteer Force — which would imply that citizens reclaim responsibility for the nation’s defense.

Change the American military system and American militarism will become untenable. Only then will elites reconsider their reflexive penchant for war. Only then might more restrained and prudent approaches to national security gain a hearing in Washington.

This article is in The Spectator’s January 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.