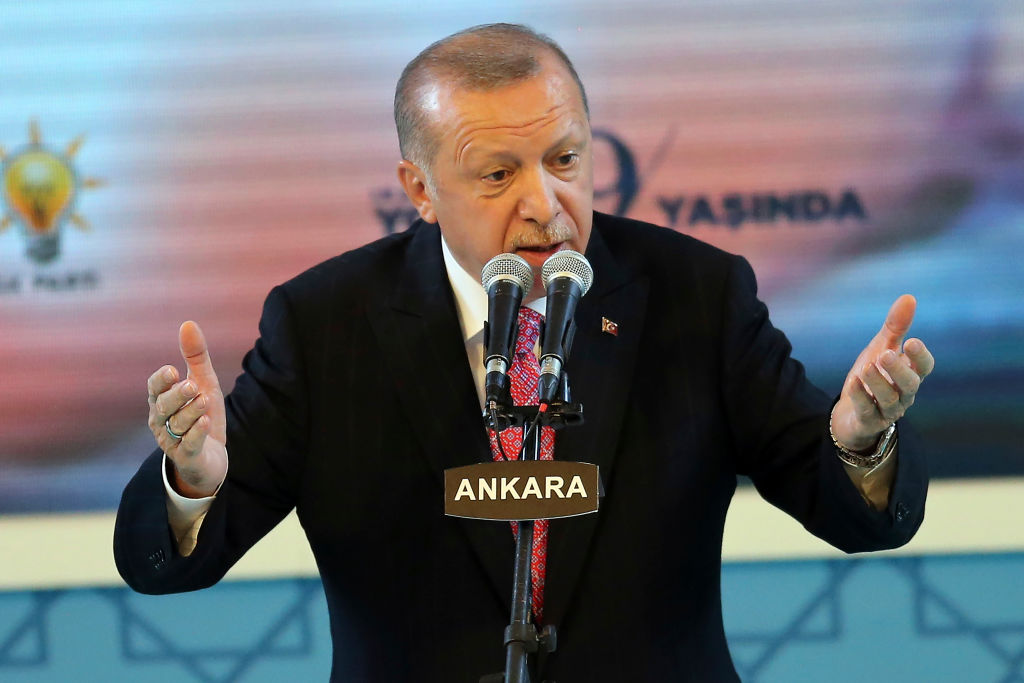

Could war finally be coming to the eastern Mediterranean? It’s not as excitable a question as it might first appear. In an article titled, ‘Erdogan’s calculated war,‘ the German newspaper Die Welt quoted sources from the Turkish military saying that President Recep Tayyip Erdogan had recently ordered his generals to sink a Greek warship, without inflicting casualties. They refused. Then came the suggestion to down a Greek aircraft. Again, they refused.

Such reports would be alarming at any time. Now they are acute. Tensions between Greece and Turkey are greater than they have been since the 1990s. Ostensibly, the problems come from longstanding competition over resources. Recent exploration has shown the eastern Mediterranean to be rich in gas fields, and both Greece and Turkey have their own economic exclusion zones (EEZ) in the sea there. EEZs are the areas in which they have the right to drill and which have become, as a result, quasi-territory.

The problems come as EEZs encroach into opposing territory. Early last month, Turkey sent the Oruc Reis ship to survey an area of the Mediterranean which it argues is within its EEZ, but which Greece claims within its continental shelf. To make matters more complicated, and precarious, in 2019 Turkey signed a maritime accord with the Libyan Government of National Accord (GNA), which expands their EEZ to encompass large Greek islands such as Crete and Rhodes. In response, earlier this month, Greece and Egypt signed their own maritime boundary agreement, which Turkey declared ‘null and void’.

Now add to this problem two things: first, an expansionist Turkey headed by a leader looking to recreate past national glories; and second: wider interlocking geopolitical conflicts that draw in players from both Europe and the Middle East.

In the Eastern Mediterranean, Turkey is guided by its ‘Blue homeland’ (Mavi vatan) doctrine, which it believes gives it the right to search for gas deposits across vast swathes of sea that encroach on the EEZs of Greece and Cyprus. This is dangerous in itself but it merely ties into a wider strategy: what has often been (sometimes lazily) described as Erdogan’s neo-Ottoman vision for Turkey, which would see the country once more expand its influence outwards in all directions as Turkey’s precursor, the Ottoman Empire, once did. This idea was encapsulated by former prime minister Ahmet Davutoglu in 2013. ‘We will again tie Sarajevo to Damascus, Benghazi to Erzurum to Batumi. This is the core of our power. These may look like different countries to you, but Yemen and Skopje were part of the same country 110 years ago, as were Erzurum and Benghazi,’ he said.

Understandably, others in the region find these beliefs alarming. And here is where things get really tricky. Turkey signed its maritime deal with Libya after it threw its weight behind the GNA in its civil war against General Khalifa Haftar, who is, in turn, supported by Egypt, France and the UAE. At the heart of this divide stands the Islamist group, the Muslim Brotherhood, which heavily influences the GNA. Erdogan supports the Brotherhood regionally while Egypt’s leader Abdel Fatteh al-Sisi, came to power by overthrowing a Muslim Brotherhood government. The two leaders unsurprisingly hate each other.

Now add France to the mix. Recently, Turkish warships intervened to stop the French Navy from intercepting a cargo vessel thought to be carrying weapons off the Libyan coast: a naval standoff ensued. Paris has now entered the Eastern Mediterranean dispute firmly on the side of Athens. When Turkish frigates accompany research vessels looking for natural gas across the eastern Med they are now opposed by a joint force of Greek and French warships, while Emmanuel Macron rails against Turkish actions at the EU and on social media.

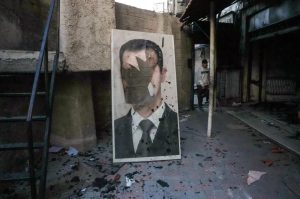

For its part, Turkey now openly disdains the United States and what Turkish politicians often term the ‘Atlantic framework’, which it believes has badly let them down in various areas, notably Syria. Instead, Ankara seeks geopolitical independence as a sign of its reinvigorated neo-Ottoman strength, seeking closer ties with states like Russia and Iran. The result merely further widens the rift.

[special_offer]

In late August, four UAE F-16 fighter jets were deployed to the Souda Air Base in Crete to carry out joint training with the Greek Armed Forces over the Eastern Mediterranean. The messaging is clear on both sides — and it is escalating.

So far much of all this is brinkmanship and signaling. If the report is true, Erdogan wanted to make a statement without actually killing any Greek troops. The problem comes not with intent but mistake or miscalculation. Brinkmanship can turn into disastrous calamity. Because if the report is true, it also showed a Turkish leader who is willing, if not eager, to escalate the situation in the eastern Mediterranean, to the point of militarily attacking his geopolitical opponent and energy competitor.

It’s a small jump from opponent to enemy. One day you’re competing for gas at the bottom of the sea, the next day you’re sending each other’s soldiers there. History shows that, in Europe, when competing turns to killing everyone suffers. And that is something that, for all the bluster, neither Greece nor Turkey, and especially the wider region can afford to let happen — the cost is simply too great.

This article was originally published onThe Spectator’s UK website.