How will the world be different after coronavirus? Will everything return to the way it was or will there be lasting change? There is one thing that will clearly be different: the UK government’s approach to China. I understand that while Boris Johnson’s grand, integrated foreign policy review has been put on hold because of the pandemic, the work on Anglo-Sino relations has been brought forward as a matter of urgency. One of those heavily involved in the development of this new policy tells me that the aim is to get Britain ‘off the trajectory of ever-increasing dependence’ on China.

The issue is not that COVID-19 emerged from Wuhan but what the crisis has revealed about the Chinese state and the UK’s dependence on it. Ministers have seen first-hand how reliant the UK is on China for vital goods — particularly personal protective equipment — and, more importantly, that this is not a normal trading relationship. They are acutely aware that if the UK is too critical of Beijing, these shipments will dry up.

Uppermost in ministers’ minds is the example of Australia, which called for an independent inquiry into the origins of coronavirus. Beijing was furious and responded by slapping tariffs on its barley and refusing imports from four key Australian abattoirs. There has also been talk of consumer boycotts of Australian produce and reports that power plants are being urged not to use coal from the country. A third of Australia’s trade is with China. It now finds itself vulnerable to a communist state that is willing to use economic links to punish countries that step out of line. This is a situation that Britain does not want to be in.

This shift in British thinking marks a rejection of the David Cameron-George Osborne ‘new golden era’ in relations with China. Osborne’s strategy was to fly into Beijing with a plane-load of businessmen and tout for Chinese investment. The hope back then was that being China’s best friend in the West would extend Britain’s time at the global top table. Rhetorically, Theresa May moved away from this desire for ever closer relations with China, but in policy terms not much changed. Then Johnson, like May, approved Huawei’s involvement in the construction of the UK’s 5G network. The security services remained confident of Britain’s ability to handle this relationship to our own benefit.

From now on, things will be different. There is now a conscious choice in the British government to diminish reliance on China wherever possible, even if it means paying more. One source at the heart of government tells me that a keystone of this new approach is that we are ‘prepared to take economic pain to reduce dependence on China’. This has the added advantage of fitting with what No. 10 believes is the public mood. One pollster, whose analysis is valued greatly by senior figures in government, tells me that for the first time there is an anti-Beijing mood out in the country. There is also a new political consensus emerging that the UK can’t be as passive as before in the face of China’s rise. Among Tory strategists the worry isn’t that Keir Starmer’s Labour party will attack this change in approach, but that it will criticize the government for not going far enough.

This aim of reducing economic dependence on China will, at first, take three forms. The first is to make sure Britain is not reliant on China for any essential imports, medical or otherwise. Second, there will be a toughening up of the rules on foreign takeovers to try to stop Chinese firms — nearly all of which are, in reality, arms of the Chinese state — from buying up vital British intellectual property. There is a recognition that the UK needs policies and regimes for policing these takeovers that it doesn’t currently have. The third aim is to stop ‘using Chinese cash to plug gaps’. These last two points will take on particular importance as both the private sector and the public realm attempt to rebuild, post coronavirus.

Johnson’s own thinking on China has changed. He showed up at the Beijing Olympics to take the Olympic torch for London and, thereafter, used this Olympic connection to attract investment into the capital. As Prime Minister, he did not share his party’s concerns about Huawei. But one of those who has discussed the issue with him recently says he ‘has moved a long way in terms of his private rhetoric’ on China.

President Xi Jinping’s China is different to the China of 2008. It has chosen to step away from opening up to the world and co-existing with democratic capitalism and now seeks dominance: first regionally, then globally.

This is particularly important as the UK is about to go over a precipice in terms of dependence on China. If Huawei does help construct the UK’s 5G mobile phone network, Britain will undoubtedly receive a much-needed upgrade more cheaply. But it comes at the price of making the UK more vulnerable to Chinese interference. Using Huawei also undermines efforts to persuade other countries to take the long view when it comes to offers of Chinese technical assistance.

Downing Street now describes its previous Huawei decision as a ‘legacy issue’. This is just as well: had the Prime Minister sought to proceed with the Huawei 5G deal he might have lost a vote in parliament, such is the depth of feeling in the party. If you want a sign of the shift in Tory attitudes to Beijing, just look at how normally cautious MPs are rushing to sign up to the new China Research Group, which wants a far more critical approach to the issue. As one of those central to party management put it to me before the Dominic Cummings issue arose, the ‘government has to do something different’ on Huawei. With Tory MPs now less inclined to accept the centre’s authority, this is even more the case than before.

Concern about Huawei goes far deeper than Tory MPs. The US national security establishment has hardened its view on China considerably in the past year and there is now a bipartisan consensus that its rise needs to be checked. As one of those advising Boris Johnson on this matter warns: ‘You can’t be in a situation where whoever wins in November, our credibility is draining with our most critical ally.’ Combine all of the above with concerns over Beijing’s bullying of Canada and Australia and you have a potent case for changing course.

One of Johnson’s closest political allies tells me: ‘The original plan is dead. It is only a matter of how they configure the shift.’ I am told that the choice now is between time limit for the use of Huawei kit in 5G infrastructure, or no role at all for the Chinese company — with ‘sentiment shifting to the harder position’.

The original decision to go with Huawei was because there was no firm from a democratic country that could do the job as quickly or cheaply. I understand that the government is now very keen to get democratic nations to co-operate on these big tech challenges.

A new alliance is envisaged by the UK: the D10 group. This would be made up of the G7 democracies plus Australia, South Korea and India. One Johnson confidant argues that ‘done right it creates a plausible alternative for developing nations’ to relying on Chinese tech know-how. Currently, China is expanding its influence in Africa by offering to help build cheap but modern communications infrastructure. The democratic world needs a co-ordinated counter-offer.

But Britain doesn’t want to go full Trump on China. The aim is for a resetting and re-balancing of relations — rather than a rupture. The hope is for a ‘reciprocal and sustainable’ relationship, so Britain would accept Chinese investment only in areas where British firms are at liberty to invest in China too. But hoping that this will happen may well be naive. Would Beijing allow a British company to build a hugely sensitive part of its national infrastructure? Or offer the UK the amount of influence that China has in universities in this country?

I understand that the government has no interest in any kind of cap on Chinese students studying in Britain, but it is keen to clamp down on the extent of Chinese Communist party influence. One No. 10 figure sums up the position as: ‘More Chinese students, fine. But universities can’t be proxies for Chinese state influence.’ One senior Tory pointed out to me that a motion supporting the Hong Kong protesters was defeated at Warwick University last term thanks to a huge turnout from mainland Chinese students. With one in three full-fees students in the UK from China, universities are vulnerable to any Beijing-organized boycott.

***

Get three months of The Spectator for just $9.99 — plus a Spectator Parker pen

***

The UK never really had a Cold War with China. It recognized the communist regime 29 years before the US did. In the late 1970s, the chief of defense staff even turned up in China and declared that the two countries had a common enemy in Moscow. But this country now needs to wise up to the threat that Xi’s China poses to the liberal global order. Academics and business leaders need to grasp this reality as much as the government does. The obscenity of the leaders of multinational business, which owe so much to the rules-based international order, hailing President Xi’s homilies on globalization as they did at Davos in 2017 should never be repeated.

The threat that the Chinese communist regime poses to the global system will become clearer between now and the fall. China’s plan is to impose new national security laws on Hong Kong. Not only does this trash the principle of ‘one country, two systems’, it makes quite clear that China intends to take advantage of the world being distracted by coronavirus and the PPE dependency that many countries have on it to advance its own agenda. Before the pandemic eases, there will be more challenges to the rules-based international order from President Xi. Perhaps in the South China Sea, perhaps elsewhere.

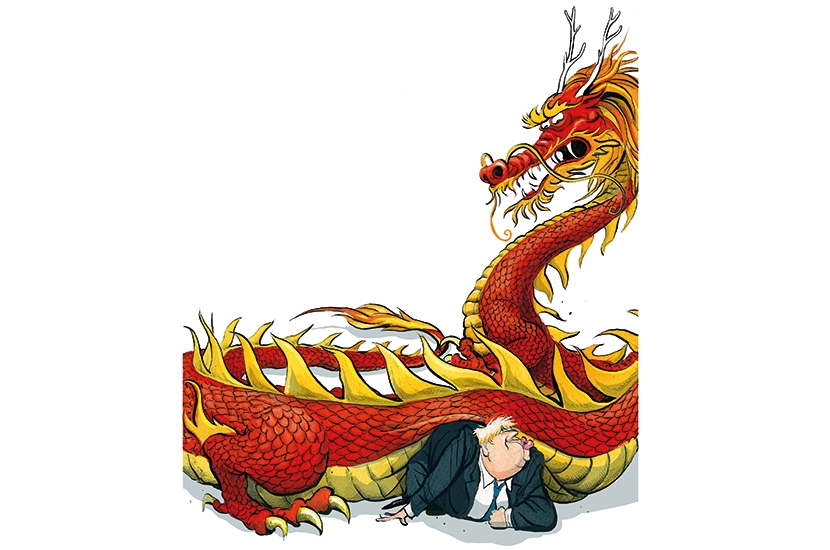

Recognizing a problem is, as any self-help book will tell you, the first step to dealing with it. The UK government has now grasped that this country is becoming overly dependent on China. The question is whether it has the energy, determination and strategic nous to get the UK out from under the dragon before it is too late.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.