Dixmont, Yonne, France

I am writing these words from my house in Burgundy. If I look over my shoulder out of the window I can see the house of my neighbor, a cereal farmer. If I look out to my right, across the fields, I can see the buildings of a cattle farmer. There is a third farm in my village where they produce cereal and vegetables.

Every two days in France a farmer commits suicide. Others walk away from the industry

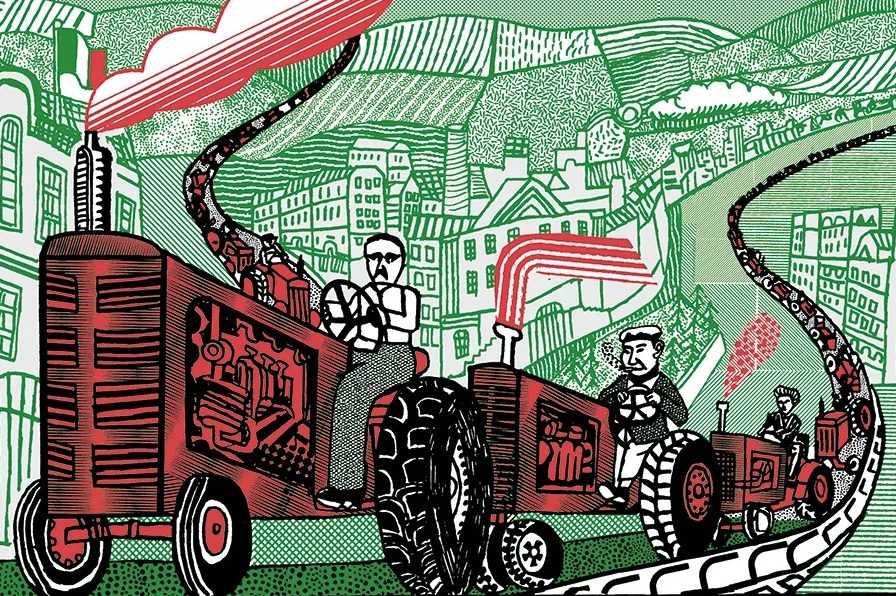

Patricia, the wife of this third farmer, dropped by last night with a crate of potatoes. Her husband has been on the front line of the growing agricultural protest movement that began two weeks ago in Toulouse. It has spread across the country. From the Mediterranean to Normandy, farmers of cattle, sheep, chickens and crops are demonstrating outside prefectures and dumping hay in fast-food restaurants. On Monday they used tractors and bales of hay to blockade motorways accessing Paris. Patricia told me their resolve is unshakeable: “We’ll go to the bitter end.”

Her fury is directed at Brussels more than Paris. European Union regulations are making farmers’ lives a misery, although they also blame bureaucrats in Paris for applying the rules so zealously. Their land is under surveillance from drones. “We can’t even trim our hedgerows without permission,” Patricia says. What grates more than anything is that they have been farming organically for many years. And for what? They make less money than they used to, but they’re still bullied and harassed on a weekly basis.

Every two days in France a farmer commits suicide. Others walk away from the industry. In my département, there were 1,058 cattle farmers in 2014 and now there are 772. In the past two years fifty-four farms have ceased to operate.

My immediate neighbor, the cereal farmer, went organic a year ago. He is also disillusioned. He tells me that he feels as if he is more of a bureaucrat than a farmer, spending hours each week filling out forms and ticking boxes.

The revolt is not confined to France. All across the EU, farmers are rising up against their governments and, specifically, against Brussels. Spanish farmers have announced this week that they too will join the protest movement because of the “suffocating bureaucracy generated by European regulations,” and Belgian farmers are also mobilizing. The demonstrations began in the Netherlands in the fall of 2019 when more than 2,000 tractors drove to the Hague. There had been growing discontent at plans to restrict nitrogen emissions, but the catalyst for the tractor protest was the proposal by one left-wing member of parliament to halve livestock numbers. “Farmers and growers are sick of being painted as a ‘problem’ that needs a ‘solution,’” said Dirk Bruins, an industry spokesman.

In Germany the anger erupted last month when Olaf Scholz’s government announced a plan to scrap a tax concession on agricultural diesel fuel. It was the breaking point for an industry exasperated by “an administrative overload.” Five thousand tractors drove to Berlin to demonstrate against a government that they claim has no respect for or understanding of the agricultural industry.

The protests in Romania and Poland are against what their farmers regard as unfair competition from Ukraine. Russia has blocked Ukrainian wheat exports by sea to Africa, so in order to assist Ukrainian farmers, the EU is importing it without quotas or import duties.

The same resentment is felt in France. When I asked my neighbor why he was protesting, he mentioned two grievances in particular: too much administration and too much unfair competition from Ukraine.

It’s not just competition from Ukraine which has moved French farmers to man the barricades, however. Patricia and her husband produce a wide variety of vegetables, but they are undercut from other countries within the EU, as well as outside it. She is not a fan of Spanish tomatoes, which flood the French market.

Two pounds of French tomatoes is $1 more expensive than a two of tomatoes grown in Spain because the Spanish produce more at a cheaper cost. “There is not enough production in France, and there is competition on production costs but also wage-cost differentials,” says Thierry Pouch, chief economist at the French Chambers of Agriculture.

Production costs are also lower for Ukrainian chicken and cereal farmers. Furthermore, Ukraine’s farming methods are not subjected to the same rigorous standards as EU farmers are. The same applies to other foreign farmers with whom the EU does business, such as New Zealanders and South Americans.

All these incomprehensible measures are tied up in the EU’s Green Deal, which was introduced in 2019 by the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen. Its aim is for the EU to be climate neutral by 2050. The commission boasted that it would turn “climate and environmental challenges into opportunities” and in doing so make “the transition just and inclusive for all.”

Many farmers were opposed to it from the outset. The Global Farmer Network, an alliance of farmers from around the world, summarized the Green Deal as the EU’s “plan to eliminate modern farming in Europe.” It was an unrealistic project, they claimed, devised by bureaucrats with no understanding of the agricultural industry.

In particular, they criticized the “Farm to Fork Strategy” component of the deal, which is supposed to promote healthier and more sustainable food in Europe by 2030. “In the next decade, farmers like me are supposed to slash our use of crop-protection products by half, cut our application of fertilizer by 20 percent and transform a quarter of total farmland into organic production,” said Marcus Holtkötter, a German farmer. “None of this, of course, is supposed to disrupt anybody’s dinner.”

Among other pieces of legislation contained within the Green Deal are regulations on reducing the use of pesticides, improving animal welfare and increasing the amount of land left fallow.

Leaving land fallow is not a new requirement. It was made compulsory in 1992 as part of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) in return for payment. It was suspended in 2008 and then reintroduced last year. For farms with more than ten hectares, 4 percent of arable land must be set aside or used for semi-natural habitats suitable for biodiversity. Some environmentalist politicians in the EU want the percentage of land left fallow to increase to 10 percent.

Farmers denounce this imposition as untenable, citing it as further evidence that the bureaucrats in Brussels have no appreciation of their industry. A fallow field doesn’t become a meadow full of flowers; it turns into a monoculture of grasses requiring regular maintenance, which costs time and effort, but for no financial reward.

Not so, counters François Veillerette, a spokesman for the NGO Générations Futures, who says these set-aside fields will be “useful to farmers” in the future.

Veillerette is a veteran environmental activist, not a farmer. I put the question of set-aside fields to a friend, Stéphanie, who runs two cereal farms in the Loiret department. She describes it as absurd. “I have eleven hectares so that means a lot of land left fallow if I want to get subsidies,” she says. “But what’s the point in setting aside so much land? The point of farming is to produce.”

Critics of the French farming industry cite the riches they receive in subsidies from the EU’s CAP. A total of close to $60 billion was paid last year, the largest slice — $10 billion — going to French farmers. Operating subsidies of $9 billion are distributed according to the amount of land and livestock numbers. The rest, $1 billion, is paid on what the farmer produces.

But it’s not as straightforward as that. Subsidies are distributed to the farmers who conform to the EU’s myriad regulations; for many smaller farmers these are impractical or impossible to follow, so they don’t get the subsidies.

Stéphanie has an unusual profile for a French farmer. She was educated in elite institutions and for a few years she was a high-flyer in the corporate world. But in her early forties she returned home to the countryside when her father became too old to run the family’s two farms.

He was a farmer all his life, but Stéphanie is now better suited to the business than he was because the industry is more about paperwork than farming. “French bureaucrats really go after us,” she says. “The rules with which we are forced to comply are stricter than elsewhere in Europe.”

Her land is also scanned by drones to check that she is complying with all the new environmental directives. Last year she was ordered to reduce her water usage by 30 percent and Paris has also made it harder to have crop insurance agents certify her yields. “Being compliant has become a nightmare because of the administration,” she says.

The farmers’ protest has crystallized the feeling within provincial France that Paris and Brussels want to eradicate their way of life. Deindustrialization was disastrous for rural France and farming is the only industry they have left; if that is destroyed then what remains of la belle France? Stéphanie believes it can be framed as the city vs the countryside. “The people making the rules and implementing them are not from the countryside,” she says. “They are ignorant bureaucrats.”

Many of the men and women blockading the motorways say they are doing so because “they have nothing left to lose.” They are fighting for their livelihoods and their way of life.

These are not Emmanuel Macron’s people. Six years ago the provinces rose up and marched into Paris in their yellow vests to protest against a new tax on fuel. The government spokesman Benjamin Griveaux looked down his nose at these “people who smoke and drive diesel cars” and declared they are “not the France of the twenty-first century.”

Oh, but they are, like it or not. The question now, not just in France but across Europe, is how the political elite responds to this agricultural insurgency?

Von der Leyen is due to discuss the crisis this week at a European Council summit in Brussels, with the EU’s twenty-seven heads of state. Many of Europe’s farmers are also expected in the Belgian capital, though they’ll be arriving in tractors.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply