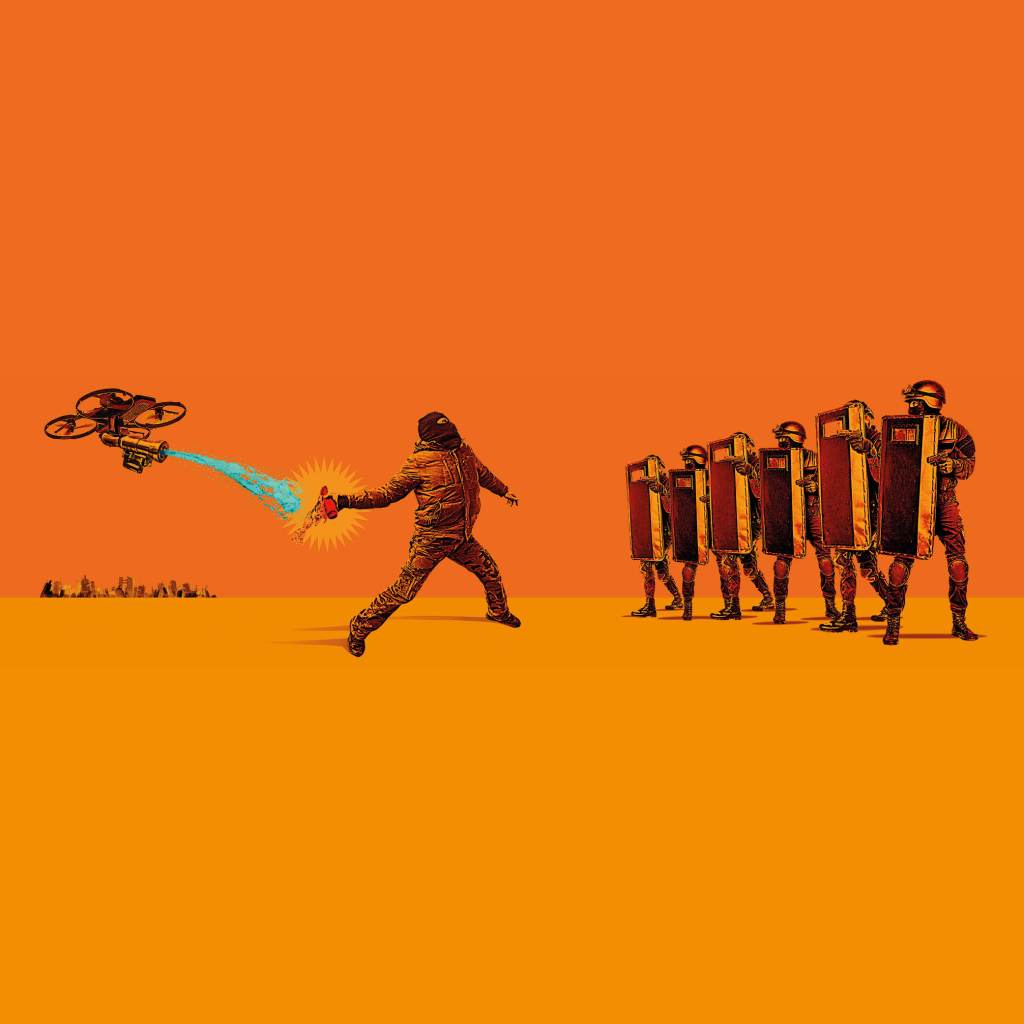

Worldwide unrest is great for those in the riot-gear business. Shields and batons have historically cornered the market as the cutting edge in crowd control, but in recent years it’s evolved to include robots, armored trucks and drones.

Milipol Paris is the homeland security expo of all expos. This is the kind of giant showroom where you will find law enforcement and private security agents checking out the newest innovations in robot dogs, armored vehicles and unmanned turrets as if they’re going from painting to painting at the Louvre.

The Milipol expo comes around every two years. In 2023, you would have seen men plugged into VR headsets killing terrorists with a pistol. You would have heard reps of the tech sectors of large corporations debut new weapons to point at unruly civilians — lasers and drones and drones armed with lasers. Norinco, a Chinese Communist Party corporation, showed off the latest advances in armored trucks, like giant Swiss army knives for crowd control, fitted with water cannons, tear gas and disorienting lasers. Norinco stands ready to “provide tailor-made system solutions to clients” with this hybrid of a garbage truck, a snowplow and a death ray.

There seems to be a microscopically thin line between new age riot gear and wartime technologies. The 2023 expo had displays of brand-new drones that could fly synchronized fleets of up to 256 units at once. Big one-armed bomb robots climbed over piles of rocks to demonstrate their smooth maneuverability. You wonder if all of these gadgets also come equipped with Bluetooth so you can listen to your Spotify on the frontlines of riots.

Before this summer’s Olympic Games, French president Emmanuel Macron reassured the world the capital would remain safe and orderly thanks to a small army of approximately 45,000 officers, much of which was pulled from the Gendarmerie, one of the two national police forces. The Gendarmerie is a branch of the French military; its responsibilities include crowd and riot control as well as police duties in smaller cities and towns and border areas. (The other branch, the National Police, is France’s civilian law enforcement body, with responsibility for larger towns and cities. The two forces often work together or in tandem.)

Crowd control has come a long way since the Chicago police department, armed only with billy clubs, sunglasses and a healthy hatred for spoiled college students, beat the daylights out of rioting hippies in summer 1968. In 2005 the department upgraded to the Damascus riot control kit. In those halcyon days, police departments issued press releases about their ability to outfit officers in upper-body and shoulder protectors, forearm protectors, knee and shin guards, elbow pads, protective gloves and gear bags. Such toys are only as good as the willingness to deploy them: the city tallied up $66 million in damage in the aftermath of the George Floyd riots in 2020.

The Chicago department’s new policy concerning crowd control, posted for public comment in June, says that its officers will “remain unbiased and opinion neutral in any communication with individuals within the crowd while affirming that the First Amendment rights of lawful participants are protected.” Democrats were awful lenient about First Amendment-inspired arson in 2020, but you get the sense Chicago authorities expected to be less tolerant of such activities with the eyes of the nation turned toward Kamala Harris’s August coronation at the Democratic National Convention.

They will have the help of the Secret Service — if you can see that as a good thing after the incompetence displayed at the failed assassination attempt on former president Donald Trump in July. Chicago PD has said that more than 2,000 officers had forty-eight hours of new training leading up to the DNC. There was also a surge in surveillance equipment covering the city — courtesy of the Secret Service.

Bryce Eddy believes that, even after the summer conventions, there are likely to be more riots due to political upheaval in the coming months. Eddy is on the board of the Center for Security Policy where he has helped partner private security with law enforcement agencies to help train for crowd control. He stood at the frontlines of the riots in LA in 2020.

“Covid and the BLM riots changed so many things,” he says. “Police departments were overwhelmed all over the country. Normally, they would rely on each other for what we call ‘mutual aid.’ But now, there have been agreements between high level security firms and police departments developing to where the security firms can offer additional services and what they call mutual aid, which is, again, usually just between law enforcement departments.”

Eddy noted that the Ventura County sheriff’s department went in to help the San Francisco police department when the 2020 riots broke out. One of the things that changed then, he says, is how private-public partnerships developed to help neutralize violent mobs. Much ink has been spilled about the militarization of law enforcement during the War on Terror — a trend that now extends to the privatization of crowd control à la Blackwater at the height of the Iraq War.

The marriage of public and private security organizations might have something to do with the lack of manpower and training in police departments, but it’s also aimed at helping with the optics. As politicians, pundits, everybody and his neighbor argue over the optics of how riots are handled, it may have become easier for law enforcement to outsource its dirty work to private entities.

When antifa descended upon Los Angeles in 2020 in the aftermath of Floyd’s murder, Eddy helped organize one of the first local crowd control partnerships between private security and law enforcement. “During Covid, you had all of the political pressure moving against the police. The city council members and the mayors were getting pressured to tell the police officers to hang back,” Eddy says. “But then you get widespread looting and rioting and that had happened in Beverly Hills during the first wave of the riots that summer.”

Los Angeles has always been at the cutting edge of developing anti-riot tactics. Eddy explains that the LAPD developed its mobile field force model after the Watts Riots of 1965. The mobile field force is the line of officers that approach a mob. The officers typically have gas masks, helmets and shields. “Their technique,” he says, “is moving down the street like linebackers.”

The thick blue line of officers has a purpose beyond intimidating would-be violent protesters, too. When riots cause fires or medical emergencies, the fire department is not allowed to enter a hostile environment to put it out; it is the duty of the baton and shield crowd to advance the line as quickly as possible to give firefighters and EMTs room to operate.

“The mob is an organism,” says Eddy. Dealing with it is “like grabbing the bad cells that are infecting the other cells. You have to do that at the beginning. There’s a certain point within which violence is really the only answer. You’re having to push people, corral people, isolate people… What people dont realize is a group like antifa is actually far more organized and far more trained than you think. If you cover some of their private chat rooms, they are ready for violence.”

Monitoring chatrooms may sound hi-tech, but combatting riotous mobs is a problem as old as time. There is little difference between Eddy’s rhetoric and that of a 1964 police training video, which shows images of volunteers pretending to be rioters as they flip over cars. “Riots and civil disobediences are on the increase everywhere,” explains a narrator, with the same kind of infomercial voice you might use to sell a space-age blender. “The first important psychological move is a show of force… the first official act is the order to disperse. Breaking the mob up. Entering to rescue, or to grab the agitator… It can happen here… Even though you think it can’t happen in your community, be prepared, train now.”

A lot of today’s crowd control tactics were perfected in ancient Rome and Greece. Helmets, shields, the application of the phalanx — the first mobile field force. Eddy thinks all the new technologies such as the ones displayed in expos at Milipol against crowds today can serve a purpose, but it really comes down to the fact that they need to train with the tools with centuries of proof behind them. “Old problems require old solutions,” Eddy asserts.

As recently as the last decade, the mere mention of the water cannon seemed controversial. In 2014, CNN reporter Rosemary Church wondered openly about its deployment during the protests in Ferguson, Missouri. “Why not perhaps use water cannons?” she asked. Even though Church’s intent seemed to be about reducing harm to protesters, she was met with swift and severe pushback from social media and her colleagues. The Revd Emma Jordan-Simpson, a Baptist minister, told USA Today, “we must not tolerate media calling up water cannons, dogs, gas chambers or other weapons used to brutalize oppressed peoples.”

Many developments in crowd control have come from the battlefield. The United States created the Chemical Warfare Service in 1918, the last year of World War One, taking over classrooms at American University in Washington for laboratories. By 1919, the CWS had invented tear-gas grenades for police to throw into protests and riots for crowd control. In 1928, General Amos Fries, the chief of CWS, said, “It is easier for man to maintain morale in the face of bullets than in the presence of invisible gas.”

Poison gases have been banned from use in warfare since the Hague Convention of 1899, though World War One combatants argued that their chemical agents somehow were not included. And lachrymal agents — tear gas — were forbidden by the Geneva Protocol of 1925. Nevertheless, police forces in the US and other countries continue to use it to disperse crowds; billowing clouds of tear gas are quintessential visuals in photographs and videos of modern protests.

This July’s assassination attempt on Trump was a terrifying episode, but as the former president pointed out in his speech at the Republican National Convention days later, the rally crowd remained remarkably calm. People didn’t stampede or surge toward the exits, a rare response in shocking and frightening moments such as a sniper shooting at a president. The risk of panic in a previously peaceful crowd, or one already on the edge of violence, offers a tricky situation to civic or military entities charged with controlling the group and maintaining the peace.

Perhaps that is why weapons designers are turning to AI to present the public with newer, softer methods. One Milipol exhibitor developed a new rubber-bullet rifle that will lock its trigger should it detect that the weapon is aimed at a human head — though even non-lethal weapons are capable of causing severe injury.

“They want to take individual judgment out of everything,” Eddy says, thinking about the scenario in which a trigger locks up automatically depending on where you’re aiming it at an enemy. “Maybe you need to take a shooter out with a rubber bullet in the guy’s face because he’s descending upon you with a knife, and you don’t have time to switch to another weapon system.”

The true future of crowd control will not necessarily be softer, but it will be invisible. In fact, it already is: the world got one of its first glimpses at a sound cannon in action in 2009 when a cruise ship was attacked by pirates off the Somali coast. It was as if a weapon from the future had arrived to fight an enemy of the past. The cruise ship was off the coast of Somalia when two boats filled with pirates made their way to stake their claim. The sound cannon, known as a long-range acoustic device or LRAD, is a speaker that uses decibels to repel a dangerous advance.

When turned all the way up, it has the effect of sunlight through a magnifying lens, making your skin feel like it’s burning; the noise it generates is painful and debilitating and tends to stop its targets in their tracks.

LRAD was developed by the American Technologies Corporation, now known as Genasys. Imagine the evolution of this device. How long will it be until they have one floating in the sky via drone and it beams down an authoritative mega-amplified voice that some will confuse with the voice of God?

If the military is currently morphing into a cyborg army and if the police are morphing into the military, that leaves the citizen in a real pickle. The citizen is surrounded by the police state, and at any moment the police state could be used against him — whether or not he did anything wrong. The police used to walk around with a billy club or truncheon, those hardened pieces of hickory shaped into a club. But as everything violent advances, paralleling war, the billy club went mostly extinct and had to be replaced with traumatic sounds and disorienting laser beams.

There are videos online sharing the science behind LRAD, and those channels circulating the videos have been digitally accosted for even sharing the science behind the LRAD — because some commenters believe just showing off the technology shows a political affiliation. The same channels created videos to teach people how to beat the LRAD. They instruct the listener on the protective qualities of earplugs and headphones, as well as the use of shields — hint: make sure the concave part is facing the LRAD — to bounce the sound back to the source.

What will come next in crowd control — weather control? In the late 1960s the US military launched Operation Popeye, a highly classified experimental cloud-seeding project intended to prolong the Vietnamese monsoon season and disrupt Viet Cong supply lines.

No matter what civil unrest is hiding in the near future, Bryce Eddy believes the best bet for individuals who anticipate mobs marching through their towns is to build community. “I have this idea of building resilient communities. When these things unravel, they unravel really quickly. You aren’t going to be able to survive for months off the grid unless you’re like a Thomas Massie. You have to have basic necessities. One is none, so have two of everything, The way we are going to survive any kind of mass civil unrest is with strong community.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply