I’m in New Zealand on a speaking tour organized by the Kiwi Free Speech Union and in some ways it’s like visiting Britain in a more innocent era. This struck me when I went on a tour of the Hobbiton movie set, where The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit were filmed. The Shire of Tolkien’s imagination, lovingly created by Peter Jackson, is an idealized version of rural England — and New Zealand, with its perfectly manicured lawns and open-faced, friendly people, is a bit like that. Although, to be fair, I may be viewing the country through rose-tinted spectacles because Labour was heavily defeated in the most recent election, winning just thirty-four out of 120 seats.

Large swaths of the educated middle class have embraced the cause of New Zealand’s indigenous people

Labour’s six years in power, with Jacinda Ardern at the helm for most of it, may provide a foretaste of what Keir Starmer has in store. Public expenditure skyrocketed, taxes shot up and the ban on oil and gas exploration imposed in 2018 left the country teetering on the edge of blackouts. But perhaps Ardern’s most toxic legacy was the deepening of racial divisions between the white European population — 68 percent of the 5.25 million total — and the indigenous Maori, who make up 18 percent (the remainder are Asians and Pasifika).

The conflict between New Zealand’s two largest ethnic groups revolves around how to interpret the Treaty of Waitangi, signed in 1840 between Captain William Hobson, the first lieutenant-governor, and 540 Maori chiefs. The nub of the dispute is over how much sovereignty the chiefs surrendered to the Crown.

Were the Maori people agreeing to throw in their lot with the British in return for peace and security? In the two decades preceding the signing of the treaty, the Maori had been beset by an inter-tribal conflict in which 20,000 of them were slain. So, if they did trade a Hobbesian state of nature for British colonial rule, it wouldn’t have been such a bad bargain. That was the view of Captain Hobson, who said the following words to each of the chiefs after they’d signed the treaty: “We are now one people.”

Or was the arrangement more of a partnership, as many Maori leaders now claim — a power-sharing arrangement, leaving room for a separate parliament, different laws and, eventually, a two-state solution? It isn’t just Te Pati Maori (the Maori party) that interprets the agreement in this way. Large swaths of the educated middle class have embraced the cause of New Zealand’s indigenous people, pointing to racial outcome discrepancies in health, education and the criminal justice system as evidence that, for all the talk of “one people,” the current system is rigged against the Maori. For these white liberals, the legacy of British rule is toxic.

Ardern is typical of this breed, and during her premiership numerous policies were introduced that racialized the Maori population and increased their sense of victimhood, such as introducing a new national curriculum that airbrushed the more unsavory aspects of their history (slavery, cannibalism, human sacrifice) and exaggerated the sins of the “settler colonialists.” Between 2017 and 2023, the people of New Zealand were subjected to numerous displays of racial self-flagellation by guilt-ridden Labour members of parliament, such as giving a new Maori name to every department of the public service.

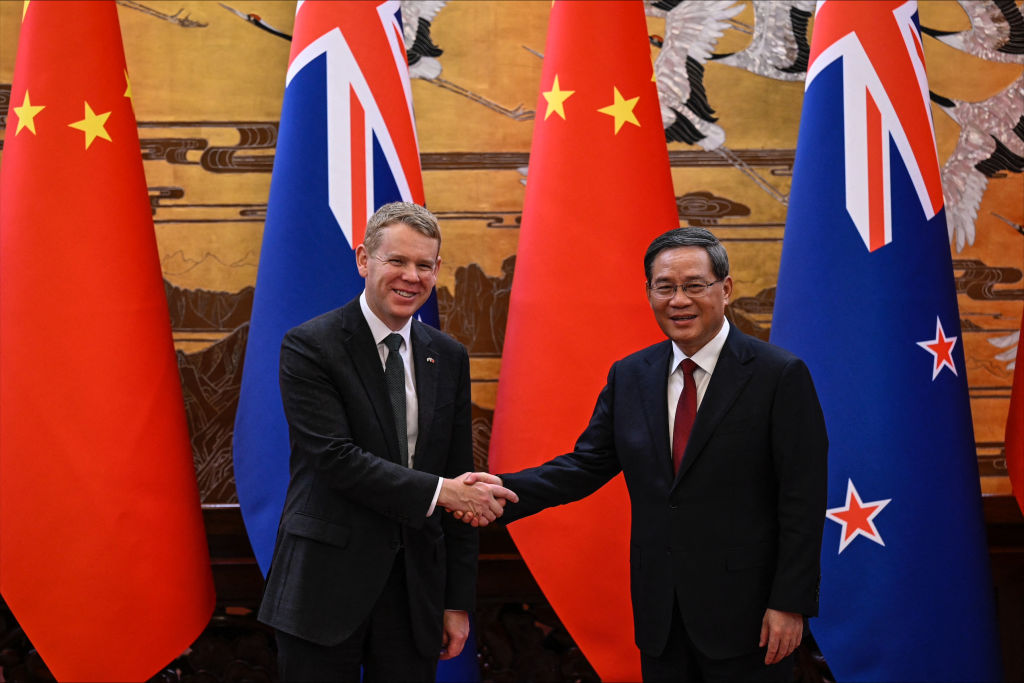

Right-wing politicians are inevitably taking up arms on the other side of this culture war. David Seymour, the leader of ACT New Zealand and a member of the government, is agitating for a national referendum about the true meaning of the Treaty of Waitangi, hoping to replicate the success of the “No” side in the Australian Indigenous Voice referendum last year, which rejected the granting of special privileges to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. But Seymour is unlikely to get his way, because the current prime minister, a technocrat called Christopher Luxon, doesn’t want to kick that particular hornets’ nest. Meanwhile, Don Brash, a former leader of the National Party, is spearheading a campaign called Hobson’s Pledge, which is calling for the abolition of reserved Maori seats in the New Zealand parliament, an end to race-based affirmative action programs and the shuttering of the Waitangi Tribunal, a commission responsible for adjudicating reparation claims brought by Maori groups.

To an outsider, it feels as if this issue is coming to a boil. I hope the “one people” side ultimately prevails. As the historian Elie Kedourie said, even a great power can be laid low by “the canker of imaginary guilt.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply