Josef Stalin knew better than Vladimir Putin. After World War Two, as the Cold War began, the Soviet dictator took the view that it was more trouble than it was worth to invade Finland again, as he had done with humiliating setbacks in the Winter War of 1939-1940.

Too many parents or grandparents of those in the Finnish audience had died in the 1939-1940 war for suspicion of Russia to have faded

And so the Finns were spared the fate of Poles, Hungarians, Bulgarians and other peoples of Eastern and Central Europe who were occupied and then communized. They had to pay a price for this absolution. The country was compelled to adopt neutral status during the decades of confrontation between the Warsaw Pact and NATO. Finnish politicians and media observed discretion in what they said about the USSR. The boon was that Finland could enjoy liberal democracy, market freedom and the rule of law.

This was the compromise known as Finlandization. It lasted throughout the remaining decades of communist rule in half of Europe. In 1995, nevertheless, the Finns cautiously sidled up to the western powers and were welcomed into the EU. But NATO membership was a red line that the Finnish government and popular opinion did not cross for fear of baiting the Russian Bear.

Finnish ministers were treated with dignity in Moscow. Russian tourists on weekend jaunts to Helsinki bought western goods in the big stores. Finns continued to show respect to Russia. The statue of Czar Alexander II, the architect of reforms in the Russian Empire in the 1860s, was left unmolested in front of the cathedral on Senate Square. The timber trade between Finland and Russia underwent steady growth. The Baltic Sea provided calm waters for commerce. Russian consumers benefited from technological imports from across the Finnish border.

Even so, I vividly remember speaking at a public conference in Helsinki in 2014 — after the annexation of Crimea — when the usual local pleasantries were expressed about the need for peace and progress. What was noticeable was the surge of applause whenever someone — invariably foreign — condemned Russia’s imperialist actions. Too many parents or grandparents of those in the Finnish audience had died in the 1939-1940 war for suspicion of Russia to have faded. There were also bitter memories about how Stalin had redrawn their borders in the USSR’s favor and displaced hundreds of thousands of Finns from Karelia or deposited them in the Gulag.

Until February 24, 2022 the Finns found ways to cope with their situation of enforced neutrality. Other countries such as Switzerland have chosen neutral status of their own volition — and of course the Swiss banks made profitable use of their country’s international neutrality for decades before the Cold War. Austria had neutrality imposed on it by the joint decisions of the Allied powers. The Austrians assumed that geography was on their side and that after the Soviet Army in 1955 withdrew from the Soviet zone of occupation, no harm could come to them from the east.

Neutrality in geopolitics commended itself to Finns only so long as it appeared to offer assurance of independence and security. Putin’s brutal invasion of Ukraine made them, regardless of where they were on the political spectrum, decide that a new military guarantee was vitally necessary. Helsinki lodged a swift application in Brussels for NATO membership. Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov responded with menacing statements about the possible consequences. That was only to be expected. But Russia’s armed forces were consumed by the difficulties of their “special military operation” against Ukraine. Rhetoric is all that could be deployed against the Finnish initiative.

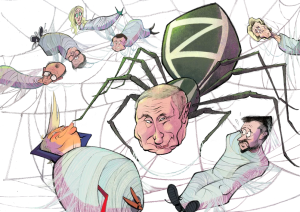

Last week NATO welcomed the Finns into its membership. It is a massive geostrategic upset for Russia because Putin and his coterie have always described NATO expansion as their ultimate fear — and they wrongly blamed America for having taken a cattle prod to herd ex-communist countries in Eastern and east-central Europe into the alliance. The truth is that those countries had a justifiable fear of Russia’s pretensions even in the 1990s and early 2000s when the Kremlin sought a cooperative symbiosis with the West.

Russian economic and political meddling in independent Ukraine scared them long before 2014 when Crimea was savagely annexed. The cyberattack on Estonia in 2007 demonstrated Russia’s willingness to use multiple methods of warfare. The invasion of Georgia in 2008 increased the nervousness about where the Russian Army would next be deployed. The more that Russia threatened neighboring countries, the more they pressed for admission to the Atlantic alliance — and the more in turn that Russia felt intimidated on its western frontiers.

Putin’s current “military operation” was predicated on a belief that victory would be immediate and overwhelming. As he had done in Crimea, he assumed that he would face NATO with a triumphant fait accompli. He never planned or budgeted for the effectiveness of Ukraine’s resistance or for NATO’s sustained support for the Ukrainian fighters. Still less had he anticipated a further expansion of NATO membership. Self-quarantined from sane voices that might have warned him against making war, Putin, who prides himself as a strategic visionary, was taken aback by the lengthening line to join the alliance. The nightmare of Russian political hawks was being realized before his eyes.

The news of Sweden’s application was bad enough, even though Turkey has as yet balked at its acceptance. But the Finnish border touches the homeland, running across 800 miles from the Barents Sea down to the Gulf of Finland. By barking out orders for the occupation of Kyiv, Putin has engineered an outcome worse for the Russian security cause than anything that he might have obtained by peaceful means. His war has brought about both the de-Finlandization of Finland and the end of any likelihood that Ukraine will consent to its own Finlandization in any strong variant.

Since the early nineteenth century, moreover, the Finns have been one of the few peoples that have achieved a degree of accommodation with overweening Russian power. With the exception of the Winter War, they have opted for compromise over confrontation — and as a result, they have often acted as a useful intercessor between East and West. Putin has recklessly thrown away their services. Finns now stand in the front line of Russia’s potential enemies. When peace comes again to the blood-soaked fields of eastern Ukraine, Finland’s historic role as mollifying mediator will be sorely missed.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.