Presque Isle, Maine

I was hoping to fly the first hydrogen balloon across the Atlantic and had been waiting for a year to get the right call from our weather men. I had postponed the trip last year, when there was not a single track that would get us from the US to Europe. Was it climate change? I had flown solo across the Atlantic in a balloon twice before, although when we say solo, the reality is a huge team of backstage staff to get you into the air safely and support the flight and the landing. This would be no different, except I would be accompanied by two fellow balloon pilots, Bert Padelt and Frederik Paulsen. In the past, weather patterns were stable for days. They now change much more quickly, as anyone trying to grill this summer will know.

Most people’s understanding of ballooning mostly comes from the beautiful, peaceful balloons seen floating across the landscape. These balloons use hot air, heated by propane burners, and so, because of the weight of the propane tanks, have a limited maximum duration of a couple of hours. We needed a few days for our trip, so a gas balloon would be better. It is a very simple concept, a gas cell filled with either helium or hydrogen. Helium has become incredibly expensive. This is partly due to its use in MRI scanners, and the Chinese discovering party balloons. Hydrogen is cheap by comparison, a by-product of several industrial processes, but it is most commonly associated with the Hindenburg disaster. Insurance companies have a list of caveats as long as a National Health Service waiting list.

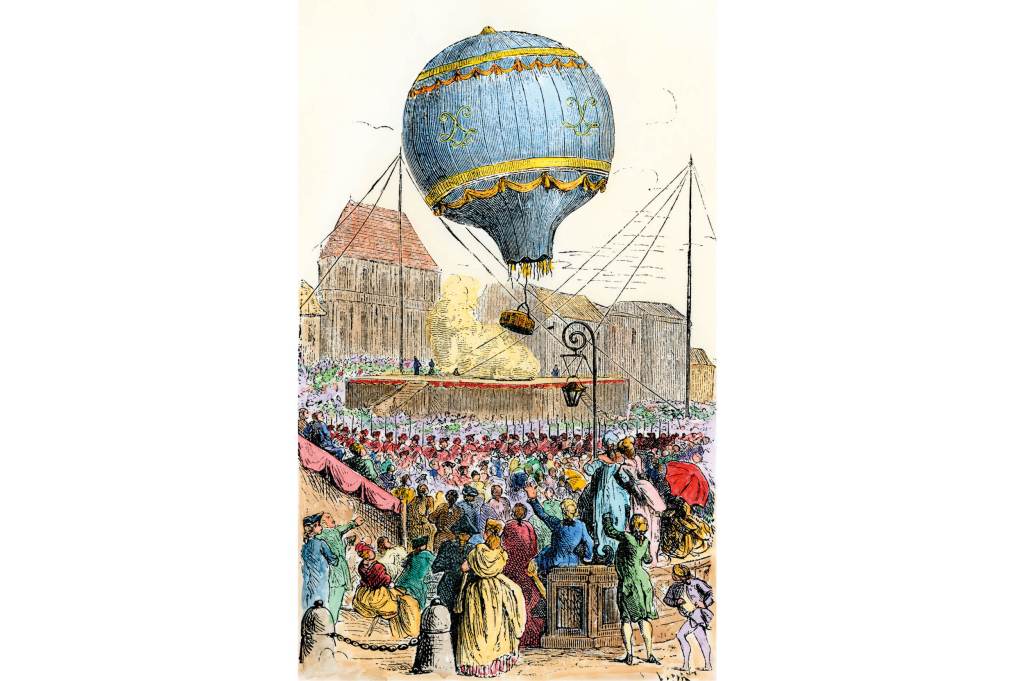

A balloon is the oldest form of flying machine. Sand is used as the ballast. To go up a couple of feet, a scoop of sand is dropped off the side. A larger “pooh” allows the balloon to go up hundreds of feet. To come down, a rope is pulled which opens a valve in the top, releasing gas. Balloons nowadays are classed as registered aircraft, which means they come with all the paraphernalia of a modern flight. We have radios to talk to air traffic control, transponders so that we show up on the monitoring equipment of other aircraft, tracking devices, emergency beacons. The food is also airline-standard: we dine on pork scratchings, swilled down with English breakfast tea, as well as the odd biscuit. American biscuits are quadruple the size of British ones and are useful for ballast.

Our Torabhaig Atlantic Explorer team consisted of Americans, English and one Swede. Someone once said England and America are two nations separated by a common language. That should extend to food, and every other aspect of life, America being as great a culture shock as any of the remote places I travel to. Watching an English and American team of balloonists discussing weather and logistics was like going back to school to learn a new language. We all know the standard differences — boot and trunk, chips and French fries — but when they started pumping hydrogen into the balloon and I said, “No smoking any fags,” that caused a real kerfuffle.

We took off from Presque Isle, a small town in northern Maine, which is known for snow and potatoes. The first ever Atlantic balloon crossing took off from here in 1978, successfully landing in France. Our predicted track showed us heading for the same destination. Using powerful computers, our team of meteorologists had our “hysplits” worked out, showing the altitude we would have to fly in each part of the crossing to get us into a field in France. The weather men in 1978 just put a finger in the air and said bon voyage.

Our team worked through the night to get the balloon inflated. It looked magnificent on the launch site, floodlit in the night sky. The three of us would be sleeping on the floor of the basket, in a space no bigger than a kitchen table. We slowly climbed into the night sky to the strains of the “Star-Spangled Banner” and immediately found the actual weather was not as forecast. How can they get it so wrong, so quickly, I thought. But as the weather gurus often tell me, they only forecast — they don’t make the weather. Speed, direction, cloud cover and temperature were all off. We were soon making a beeline for Greenland, with target altitudes that would have left us too low on ballast to make it across. We discussed the latest patterns with the control room and tried for eight hours to find the right tracks, but they were simply not there. We had some quick decisions to make: ditch in the cold North Atlantic if we ran out of sand, which — on our current usage — we surely would, and I hate swimming. Or quickly do an emergency landing on the ever-dwindling land below us.

We landed in a French-speaking part of the world, just on the wrong side of the Atlantic. We ended up eighty-eight miles away in New Brunswick, Canada, which was disappointing. What’s more, Canadian mosquitoes love sweet English blood. Bug spray was not on the kit list, which was a terrible omission. We gave the balloon basket a quick brush, put it in storage and left Maine for England by plane, with our tails between our legs. It has now been a week since we landed, but what a week: the election, European soccer, Wimbledon, Formula One. As all those teams know, you win some, you lose some. It’s only a failure if you don’t at least try.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply