There’s an old adage in the gambling business: “You never hear anyone say ‘I used to be a bookie but then I went broke.’” So if you’re betting on the DraftKings sportsbook app going under soon, even though the company lost $242 million in the fourth fiscal quarter of last year, you’re as big a sucker as the people who think they’re going to get rich by hitting a ten-team parlay. The company brought in $855 million in revenue in the same time period, up 81 percent from the previous quarter, and increased its user base to 2.6 million, up 31 percent. It only lost money because it spent a fortune on advertising and promotions, which, given the other numbers, have clearly been successful. If you bought stock in DraftKings or its chief rival FanDuel right now, you wouldn’t be too late. The golden age of sports app gambling in America has barely begun.

The era began in 2018, when the Supreme Court, in a landmark decision, Murphy v. National Collegiate Athletic Association, struck down a federal ban on state authorization of sports betting. The national Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act, or PASPA, prevented states, and individuals in those states, from operating any kind of sportsbook or benefiting from any type of sports gambling. The law exempted four states — Nevada, Oregon, Delaware and Montana — which already allowed sports betting at the time Congress passed PASPA. The day the Court struck down the law, sports betting was open for business in Pennsylvania, which had already passed a law saying sports gambling would be legal in the state as soon as the law allowed. DraftKings and FanDuel were already gearing up their algorithms to rush into the breach.

As of today, online sports gambling is legal in more than twenty states, with more than a dozen others allowing in-person sports books, and several more states pending. According to the American Gaming Association, Americans legally wagered $73 billion on sports in the first ten months of 2022, up more than 70 percent from the previous year. Sports-betting companies made nearly $6 billion in profit. And New York State alone made more than $1 billion in tax income from legal-betting taxation, much of it coming from mobile revenue. The grift is on — and it’s not even illegal anymore.

In addition to FanDuel and DraftKings, which own the vast majority of the market, there are dozens of other online sports books, with the Caesars and MGM casino corporations topping out the second tier. The bulk of the app volume remains with the standard sportsbook options — picking a game winner, point spread, total points or goals scored — because the apps allow higher limits for those and they’re more accessible to the average bettor. In some states which have not yet legalized online gambling in full, you can only use the apps for fantasy sports. But in the legal states, people can bet on anything and everything online.

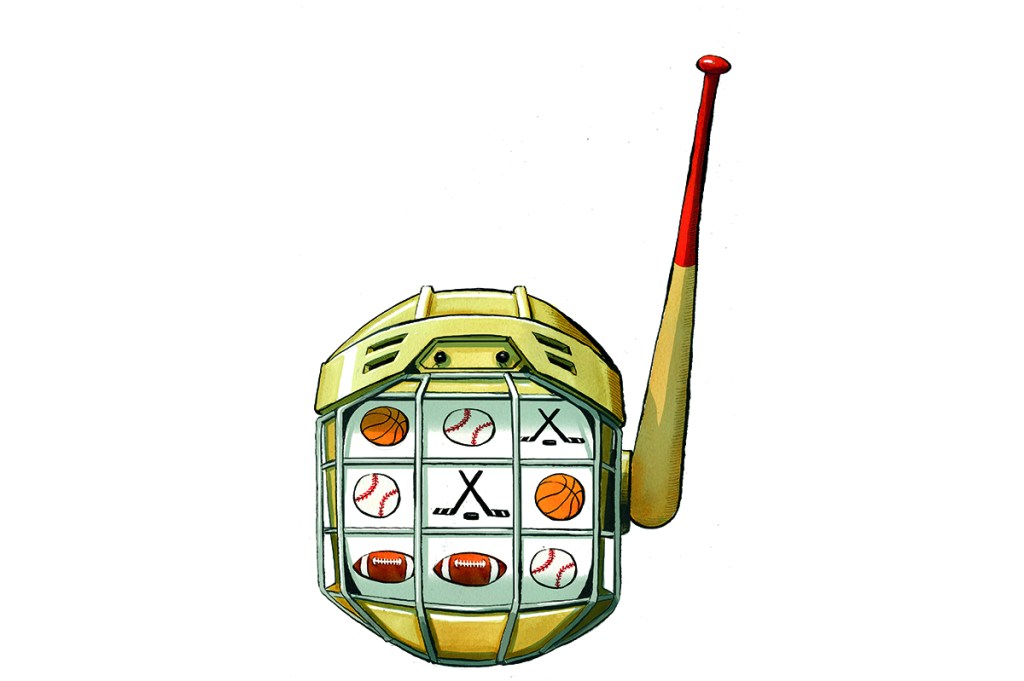

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]The apps have a phalanx of experienced oddsmakers working for them, and they have access to infinite amounts of data. They punch a few numbers into the back end of an algorithm, which spits out projections, and then they convert those into odds, generating thousands of different options. On the apps, people can bet who will score the next goal in a hockey match, how many total bases a team will accumulate in a baseball game, who will hit the next home run, or how many yellow cards a soccer team will accumulate. The apps particularly push the individual player bets, because they can sandwich those into parlays.

And the parlays are what the sports books are really pushing. As one experienced Vegas oddsmaker told me, “If you have four percent of juice on the game, and you combine two or three games, the book goes from taking eight percent to taking eight to nine to taking thirteen… over time. Like in poker, the rake eventually gets you. It’s the same thing.”

The gambling doesn’t even always involve sports. I spoke with David Leong, a clinical social worker in California (and a gambling addict in recovery), who runs a nonprofit called Stop Betting Sports. He says that “prop bets,” which is what the books call anything that doesn’t involve picking a winner or a point spread, have been the ruin of many a client.

“It’s become more than just betting on the spread,” he says. “For the Super Bowl, some of the biggest bets are the coin toss, what color is the Gatorade, is the National Anthem going to be under/over ninety seconds. What color shoes someone is going to wear. The game of football doesn’t even come into play. Whatever’s in front of you, you’re going to bet on.”

Though there are some degens who pour their fortunes — large, small, or nonexistent — into sports gambling, the vast majority who use these apps either lose a small amount of money, break even, or come close to breaking even. Then you have the sharps, people who understand the system and how to game it. I personally know half a dozen poker players who maintain their bankrolls through self-developed algorithms that generate daily fantasy sports lineups through the apps.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]“There is a path to making some money, I wouldn’t say a lot, unless you are well-bankrolled, and very disciplined, and lots of other things,” says my mysterious unnamed Vegas oddsmaker source. “There are some people who have the discipline and the knowledge and the information. But not many.”

If the books see some random user hit a $600,000 miracle parlay, they’ll raise their limits. The industry knows that no one loses money to parlay bettors, they just let them hold it for a while. But both DraftKings and FanDuel will kick users out if they see them winning too much. If all their betting is on prop bets, that raises red flags. Working edges with unusual betting patterns raises suspicions. The apps end up sending sharps to the rail, back to live sportsbooks, which also often ban them. The apps want their customers to lose, not win. And most of the players do lose, either quickly or over time.

“These companies know that there are people who are going to win once in a while, and win big,” Leong says. “But it’s not going to outweigh the losers. That’s what these companies are banking on. They want the compulsive gamblers, the degenerates who keep losing and losing and won’t stop.”

Sports books are just the tip of the spear at FanDuel and DraftKings, which are actually customer acquisition businesses with sports books attached. Both operate massive online casinos that include video blackjack, roulette, baccarat and sleazy slot games with names like “Cash Eruption,” “Extra Chili” and “Chicken Fox Jr.” So even if bettors are hitting their parlays, the online casinos are getting that money back elsewhere. “If sports betting is going wrong,” Leong says, “the number one thing you’re going to do is chase your losses at blackjack or at the casino, online or off. These apps pretty much allow you to do it all.”

At the end of the day (or in the middle of the night), these apps are just taking something out of the shadows that had been going on anyway. The 2018 court ruling legalized a longstanding consensual vice, akin to the current state-by-state efforts to legalize marijuana. It’s not as though they invented gambling: If people aren’t able to gamble on DraftKings, they’ll do it with their bookies.

The difference is that their bookies can’t afford to spend millions of dollars on TV commercials that feature Mark Wahlberg and Jamie Foxx. People are always going to gamble — and now the dam has burst. It remains an open question whether that burst dam will end up drowning thousands, or just costing millions of people a bit of money while providing them some basic entertainment. Or maybe both. Either way, online, as in-person, the house always wins.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]