Self-help has been a popular American pastime at least since Dr Diocletian Lewis toured the countryside in the 19th century. Dr Dio preached to huge, rapt crowds about the salutary effects of gymnastics, chastity, sobriety and loose clothing. He eventually cofounded the temperance movement. Having deprived Americans of their preferred entertainment, Dr Dio went on to invent the beanbag.

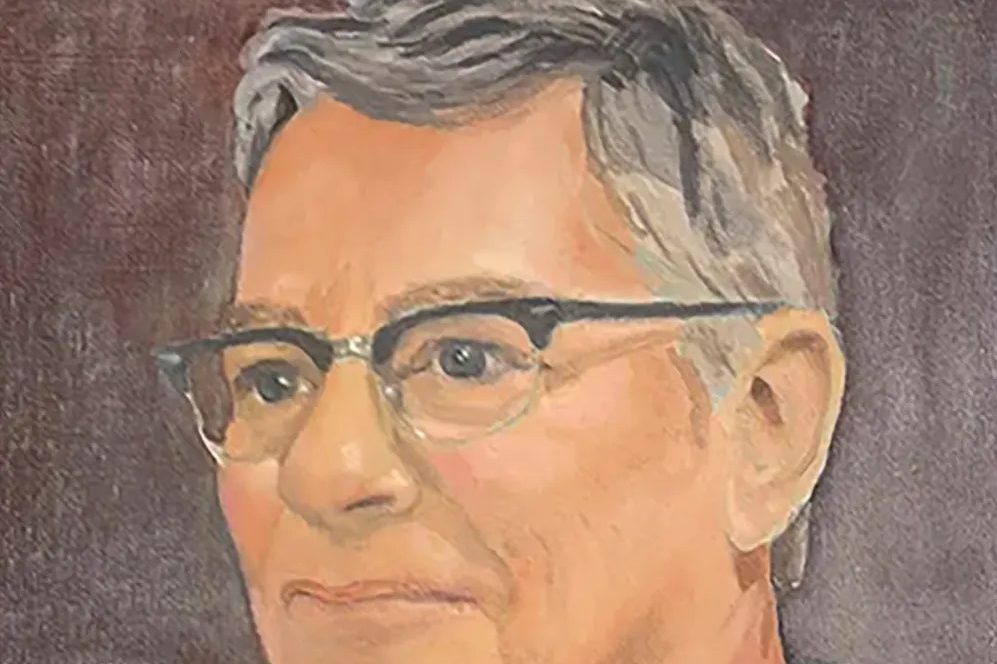

A century later, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen Covey sold tens of millions of copies and inspired spinoffs for families, companies and teens, as I learned when my mother gave me a copy during a particularly ineffective period of my adolescence. Covey, a Mormon, was the spiritual heir to the clean-living crusaders of the temperance movement. He was also a forebear of what today remains a booming industry of books about the tactical improvement of life. As someone who still needs a lot of help, I’m a fan, and I’m not alone: after years of steadily increasing sales, self-help books sold nearly 55 million units in 2020.

Covey’s 7 Habits are a little different from the booming ‘habits’ category of self-help today, though. He refers to habits of thought, like ‘be proactive’ or ‘think win-win’; today, mega-hits like Atomic Habits by James Clear or The Power of Habit by Charles Duhigg refer to daily routines. Run every morning for a year. Put your alarm clock out of reach, so you can’t snooze. Floss. ‘You are what you repeatedly do,’ as Aristotle didn’t actually say, but any of these authors would.

Sitting on the shelf alongside the habit books are those I think of as optimization self-helpers. Authors like Tim Ferriss and Gary Vaynerchuk encourage you to run your life like a small business: efficiently and profitably. Start a side hustle in your spare time and live by the 80/20 rule: 80 percent of results come from 20 percent of efforts. The 9-to-5 job, is the enemy of the optimization crowd. They dream instead of early retirement, in which they can Crossfit and podcast in perfect, efficient solitude.

The spiritual cousin of the optimize crowd is the amped self-help book: notable entrants are Can’t Hurt Me by David Goggins, Extreme Ownership by former Navy Seal Jocko Willink and the Bulletproof series by Dave Asprey. They don’t teach you how to do anything in particular — well, except to put butter in your coffee, in Asprey’s case — but they do get you hyped about absolutely crushing life. These books have a sister in the girl-power genre, a bustling category with classics like Eat Pray Love and any book by Oprah, as well as the recent, glittery mega-bestseller Untamed by Glennon Doyle. These books are about empowerment, whether through masochistic self-punishment or fanatical self-acceptance.

But if you, like me, judge a book by its sparkly cover, you might instead enjoy the more understated category of what I call neuro self-help, books by PhDs and MDs, filled with charts, graphs, clinical vocabulary and implausibly confident statistics. Despite my mother’s attempts to make me a more effective teen, I didn’t really embrace self-help until a wise friend, tired of my whining about a breakup, pressed a copy of Carol Dweck’s Mindset on me a few years ago. I now reread it annually to be reminded of its basic, evergreen message: the key to happiness is the belief you can improve. I recovered from the breakup with renewed optimism about my own ability to choose positive experiences, precisely 40 percent of the time.

I’ve barely begun to cover the many areas of self-help: crunchy self-help, for the aspiring mindful; leadership self-help, for bosses; romantic self-help for the insufficiently love-lingual; pottymouth self-help, which you know when you see. But, as with so many areas of life, the Covid year has brought new scrutiny to this seemingly thriving field.

For one thing, productivity-based self-help faces a gathering backlash. Working parents and essential workers made a mockery of the optimization genre as they navigated dangerous or downright impossible conditions. Conversations about burnout and exhaustion replaced productivity tools like habit and mindset in the discourse about work, while terms like ‘toxic incompetence’ questioned the 80/20 rule: a boss who thinks he’s above the ineffective 80 percent of work may instead just be shipping it downstream to his underpaid and overburdened juniors.

Meanwhile, increasingly woke readers can’t help but notice that books about improving one’s personal habits ignore troublesome systemic factors from the boardroom to the bedroom. And don’t even think about mentioning the girlboss, that once-ubiquitous self-help meme of the ruthless female capitalist. When COVID exhausted working mothers or chased them out of the workforce entirely, it put the lie to the girl-boss trope — and good riddance.

When self-help readers try to course-correct away from obsessive productivity, they’re seeking relief from anxiety and self-doubt: see recent bestsellers like Unwinding Anxiety by Judson Brewer, Think Like A Monk by Jay Shetty and Get Out Of Your Head by Jennie Allen. With more than 40 percent of Americans experiencing anxiety and depression in the past year, this seems far more urgent than ‘crushing your goals’.

I’m hopeful about the current self-help trends. As long as people seek advice from some source outside themselves, they tacitly acknowledge that some truth exists and the good life is attainable. Long before Dr Dio toured the Heartland and liberated women from their corsets, the Book of Proverbs promised, ‘Whoever listens to me will live in safety and be at ease, without fear of harm.’ That promise may not be fulfilled by every huckster with a YouTube channel and a diet plan, but it remains powerful; that, I think, is cause for optimism. Then again, that may just be my growth mindset talking.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s June 2021 World edition.