Close to a century ago, in 1928, Alfred E. Smith, the governor of New York, became the first Catholic nominee of a major political party. A predominantly Protestant America was suspicious of Smith, who, among other things, opposed Prohibition. New York lawyer and Episcopalian Charles C. Marshall published a letter questioning Smith’s fitness for office. Among other criticisms, Marshall quoted papal encyclicals that denied the legitimacy of religious freedom as popularly understood by most Americans. “What the hell is an encyclical?” Smith is reported to have responded.

Concerns about the irreconcilability of American republican government and Catholicism were nothing new. Charles Carroll, the only Catholic to sign the Declaration of Independence, had to defend himself against charges that his allegiance to the pope would undermine his loyalty to the new nation. As Christopher Shannon explains in his new book American Pilgrimage, influential Calvinist minister Lyman Beecher, in a widely read 1835 tract called “A Plea for the West,” warned that immigrant Catholic hordes would exploit the power of mass democracy to usurp control of American political institutions and impose Catholicism on the country. Explains Shannon:

In sermons delivered throughout the 1820 and 1830s, Beecher reminded Protestants across denominational lines that “the Catholic Church holds now darkness and bondage nearly half the civilized world…. It is the most skillful, powerful, dreadful system of corruption to those who wield it, and of slavery and debasement to those who live under it.”

In 1834, Beecher provoked the burning of an Ursuline convent in Charlestown, Massachusetts.

Though today Catholic institutions (including churches) remain a frequent target for activists and vandals, it is less because of the otherness of the Catholic faith than its identification with the same patriarchal, religiously informed, bourgeois norms liberal ideologues aim to dismantle. Indeed, in 2022, it would be more accurate to say that rather than threatening WASP culture, Catholics are America’s best chance of preserving it.

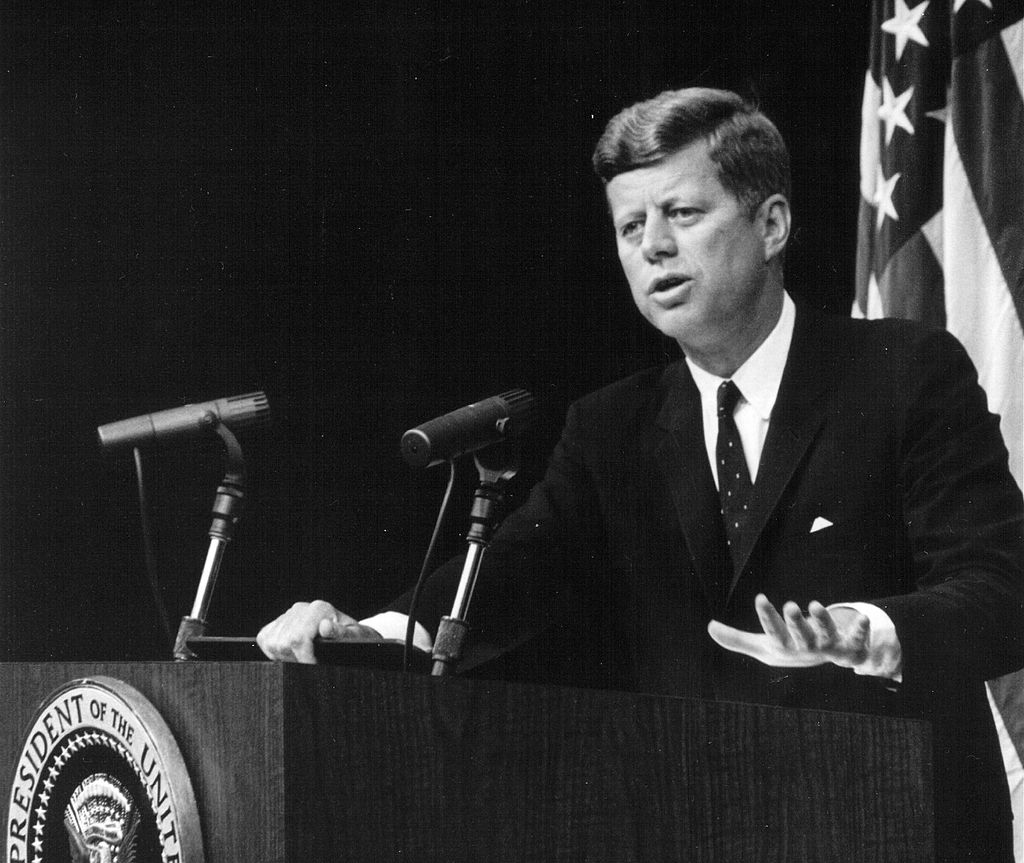

Only a generation after Smith’s loss to Herbert Hoover, Democratic presidential candidate John F. Kennedy gave his famous address to the (Protestant) Houston Ministerial Association in 1960. Kennedy declared, “I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute. …I believe in a president whose religious views are his own private affair.” Shannon observes, “Aside from attendance at the church of his choice on Sunday, Kennedy could have been any other upper-middle-class white American.” Indeed, most Catholics in post-World War II America ascended to the middle class, with all the requisite patriotism and socio-economic moderation and respectability the lifestyle demanded.

Catholics in many respects mimicked the institutions of middle-class WASP America. The Knights of Columbus, a fraternal society founded in 1882, was like the Elks or Masons but for Catholics. It aspired for popular recognition of Catholics, lobbying for the establishment of Columbus Day as a national holiday, which 30 states had adopted by 1912. There are Catholic versions of the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts.

In 1955, historian Richard Hofstadter contrasted WASP and Catholic political traditions. The former, an “indigenous Yankee-Protestant political tradition,” was founded upon “middle-class life” and demanded “disinterested activity of the citizen in public affairs,” governed “in accordance with general principles and abstract laws,” and celebrating individualism. The latter, Hofstadter claimed, was “founded upon the European backgrounds of the immigrants, upon their unfamiliarity with independent political action, their familiarity with hierarchy and authority, and upon the urgent needs that so often grew out of their migration.” It was based not on disinterested respect for universal republican principles, but on “personal obligations” and “personal loyalties,” a system of values that elevated “the urban machine.”

These distinctions largely disappeared in the latter half of the twentieth century. Catholics now comprise a significant percentage of both houses of Congress and a majority of the Supreme Court, and one occupies the White House. Prominent conservative Catholic intellectuals and politicians, such as Patrick Buchanan and Robert Reilly, defend the American founding. Hillsdale College, which in many respects represents a bastion of old-school, religiously devout WASP identity, has a strong Catholic student population, and employs practicing Catholics such as Matthew Spalding, Bradley Birzer and Matt Mehan. Many institutions, from CatholicVote to the Acton Institute, endorse a political vision that is aligned with political and cultural principles traditionally associated with WASP America yet deeply influenced by Catholic teaching.

Moreover, if one were to name the largest demographic in the United States that vocally seeks to uphold the old, bourgeois Protestant norms of familial respectability and personal responsibility, professionalism and a diligent work ethic, neutrality before the law and free enterprise, it would be politically conservative Catholics. It is Catholics who valorize the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, and the rest of the nation’s cultural and political inheritance. Catholics defend Western Expansion and the South. It may be a strange irony that conservative Catholics are the ones defending a tradition and culture that perceived them with suspicion, if not open antagonism. But that just goes to show how complete the enculturation experiment has been.

The reasons for this assimilation are undoubtedly many and complicated, but Shannon hints at one. He writes:

British tradition had bequeathed an anti-Catholicism more of politics and culture than of doctrine. This tradition saw Catholic fidelity to Rome as a symptom of a divided loyalty that threatened to expose England, and later America, to political manipulation by a “foreign potentate.”

In post-war American Catholicism, doctrine seemed less of an obstacle to being both a good Catholic and a good American. The Second Vatican Council’s 1965 issuing of Dignatis Humanae, which was widely interpreted as an endorsement of religious liberty, dispelled the types of concerns leveled by people such as Charles C. Marshall a generation earlier. The founders, claimed prominent Catholic scholar John Courtney Murray, “built better than they knew.” And large numbers of Catholics, having served admirably in multiple American wars, started prosperous businesses and entered the highest political offices of the land. This proved that in practice, Catholics were indistinguishable from their Protestant counterparts.

That remains largely the case today, though some may object that the growing popularity of post-liberalism and integralism in traditionalist Catholic circles presents a rebuke to that postwar consensus. I’d offer two responses: first, post-liberalism and integralism are a minority, not even among conservatives, but among right-leaning Catholics. Second, even post-liberals’ criticism of classical liberalism seems in significant part to be motivated by a feeling that the nation’s elites in their embrace of radical sexual and racial ideologies betrayed the bourgeois norms Catholics had labored so strenuously to secure.

In other words, even if they do not share the same religion of the nation’s once dominant culture, right-leaning Catholics represent the largest and most faithful inheritors of that older WASP understanding of the good life. It’s also very possible they represent the best hope for its survival.