When the UK’s Prime Minister Rishi Sunak announced that the 2030 ban on new gas and diesel cars would be delayed by five years, he framed it as a common-sense move. What he didn’t say is that he had been advised that, had the original deadline stuck, Britain’s electric vehicle (EV) market would have been handed over to China. Going green, Sunak was told, would mean going Chinese.

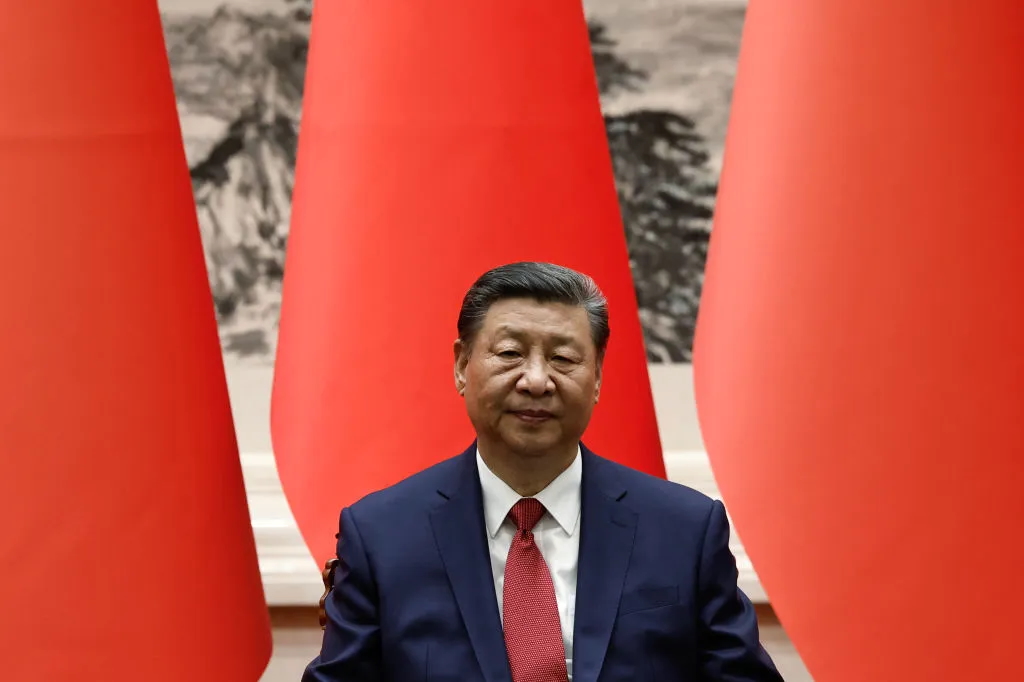

At the COP climate summit in Dubai starting this weekend, other leaders will have reached the same conclusion. They’re all a bit late. With little fanfare and a lot of state help, Chinese companies are now world leaders in wind, solar, hydro, lithium batteries and electric cars — dominating either the sectors or the supply chains that support them. The world’s greatest polluter, which emits twice as much greenhouse gas as the United States, has become the engine of the green revolution. COP’s emission-reduction targets may be good for the planet. They will be even better for the Chinese economy.

Beijing is miles ahead in a tech race that western countries hadn’t quite realized was under way

Xi Jinping spotted the business opportunity long ago. “Clear waters and green mountains are mountains of silver and gold,” he said two years ago at another COP summit. The gold is pouring in. Chinese companies produced more than three-quarters of the world’s solar panels last year. They also made three–quarters of the world’s lithium-ion batteries, essential for electric cars. Within a decade, Chinese companies are set to own half of all the lithium-ion battery factories in Europe. A third of EVs sold in Britain are made in China: a figure expected to rise quickly as marques such as MG, BYD and Nio become more popular. They’re sold at prices that European and American rivals struggle to compete with.

Solar, batteries and EVs form what Chinese state media calls “the new three,” or xinsanyang, replacing the three manufactured goods that used to drive the economy (clothing, furniture and home electronics).

The EU has started an investigation into how Chinese cars can be sold so cheaply. EU companies controlled nearly a third of global solar panel production until the 2008 financial crisis, in the aftermath of which solar subsidies were wound down and China seized its moment. “We must not repeat in the electric car market the mistakes we made with solar,” Emmanuel Macron warned earlier this year. The Biden administration, meanwhile, has responded with Beijing-style state subsidies for renewables — $370 billion under the guise of the Inflation Reduction Act — saying that the US is “re-entering the climate fight.” Sunak knows that Britain cannot compete on subsidies.

What is clear is that the vaunted “green jobs” are more likely to be in Shenzhen than in Sheffield. “Communities up and down the east coast can see wind farms,” Gary Smith, boss of the GMB union, told The Spectator in September. “But they can’t point to the jobs.” Boris Johnson once promised 250,000 new jobs in the “green transition” (60,000 alone in wind). Three years on, Britain is the world’s second-largest installer of offshore wind power, yet still imports almost all of its turbines. Of the world’s largest fifteen wind turbine manufacturers, none are British, while ten are Chinese. Yet the “road to net zero” continues to hollow out Britain’s existing industry: right now, 3,000 jobs are on the line in Port Talbot as Tata Steel moves to lower carbon tech.

Beyond the economic headache, there are legitimate concerns over the ethics of Chinese green technology and the security implications of its dominance. A great many of the country’s solar panels or their constituent parts come from Xinjiang, probably made by Uighurs coerced into laboring in mines and factories. Modern EVs have the potential to record huge amounts of information, such as location data and even conversations between passengers. Given that China’s major companies ultimately answer to the government in Beijing, how safe will people’s data be if they buy such products? Then there’s the real possibility that these cars could be switched off remotely, as their software is periodically updated by the manufacturer. MPs earlier this year sounded the alarm about the risks this poses, warning of the threat that China could remotely control the vehicles’ steering and brakes.

Politicians in the West now talk about “de-risking” from China (preferring that to the Trump-era policy of “decoupling”). But in their drive to achieve net zero without supporting their own green industries, western countries seem too willing to embrace the risks. They are starting to realize that Beijing is already miles ahead in a tech race they hadn’t quite realized was under way.

How can China profit from everyone else’s clean-up mission while being a worse emitter than the countries that are its customers? In fact, China’s dirty reputation has helped Beijing to avoid international scrutiny — it seemed incongruous that Xi, king of the coal plants, could also be pushing for the development of solar panels, wind turbines and electric cars.

Xi sees no contradiction. China wants to grab the obvious export opportunities of renewables and assuage the disgruntled middle class by cutting pollution, while continuing to burn record amounts of coal for its own energy needs. China’s poorly connected grid also means that some provinces are forced to resort to coal because renewable energy produced on the other side of the country can’t be delivered to them.

Beijing isn’t as good at playing the long game as its critics (and some of its cheerleaders) say, but its industrial policy on renewable energy is a good example of how authoritarian governments can wait out and outwit their democratic rivals.

The research and use of green tech was first put on the ruling party’s agenda in 2005, when a renewable energy law was passed. After the global financial crisis, Beijing earmarked $29 billion in its crisis stimulus package for energy-saving, emissions–reducing and ecological engineering projects. By 2012, two-fifths of the world’s solar cells were being produced by Chinese companies.

In 2015, the same year that Xi signed up to the Paris Agreement with other world leaders, including Barack Obama, the Chinese leader also announced the “Made in China 2025” strategy. It was a ten-year plan to move the country away from cheap, labor-heavy manufacturing to high-tech sectors such as robotics, semiconductors and — crucially — green energy. Subsequent five-year plans have kept local governments and companies on track with quotas and subsidies. The business opportunity was clear: as the developed world’s climate guilt worsened, there would be increased demand for solar panels, wind turbines, electric cars. Who better to supply them than the factory of the world?

Orders from above spurred industry, state-owned enterprises and local governments into action. The People’s Bank of China started backing cheap loans to be given out by regional banks to fund green projects: so far Chinese banks have lent some $44 billion in this cause. Government money was also spent on creating domestic demand for renewables, tapping into China’s huge market of 1.4 billion people. In Shanghai, for example, free license plates were given to those who bought EVs and hybrids, whereas a plate for a new gas car costs at least $13,000.

Compare this to the stop-start approach taken by western governments. In 2012, after China’s takeover of the solar industry, Europe introduced tariffs on Chinese solar panels, before lifting them six years later in the name of net zero. In the past couple of years, however, a number of European solar companies have gone bust in the face of Chinese competition, and now the EU is debating whether to reinstate tariffs once again.

Or consider BritishVolt, a British battery start-up that Boris Johnson hailed as “part of the Green Industrial Revolution.” The firm collapsed in January, in part because the government wouldn’t give it an advance on a $130 million grant when it ran into difficulties. Ten months on, the gigafactory in Blyth stands half-built, and BritishVolt’s former boss has pointed the finger of blame at Sunak and government bureaucracy. Today, the only gigafactory being built in the UK is overseen by Envision, a Chinese multinational.

China’s green overhaul is about more than just winning western contracts. The CCP is on a drive to clean up at home, having faced mounting criticism from the country’s new middle classes about air and water quality. At the time of the 2008 Beijing Olympics, the Ministry of Health admitted that air pollution was killing hundreds of thousands of Chinese citizens each year. Residents in Beijing, the worst-affected city, began sharing the US embassy’s air quality ratings because they didn’t trust the official figures.

The People’s Bank of China started backing cheap loans to be given out to fund green projects

The ruling party declared a “war against pollution” nine years ago and its population takes this quite seriously, as I’ve seen for myself. When a family friend took me around his new four-story home in my hometown of Nanjing a few years ago, one of the first things he showed off was the central ventilation system which filtered the outside air. Although China is the world’s 13th most polluted country, its air is becoming cleaner remarkably quickly. It took London fifty years to halve its air pollution; Beijing seems to have done the same in five, according to international observers.

Hundreds of billions of dollars have also been spent on cleaning up China’s rivers and on the “Green Wall of China” in the Gobi desert, a re-forestation project which is intended to reclaim an area the size of Ireland each year. Forests cover almost a quarter of the country, up from 17 percent in 1990. China is on track to have its carbon emissions peak by 2030 and aims to be carbon neutral by 2060: a tough target, but not impossible.

Other countries are committed to reaching net zero sooner, which on current trends will ensure that China’s grip on the ever-expanding green-tech sector will keep tightening. It’s not too late for the West to catch up, though. The EU and US are digging deep. Britain doesn’t have the cash, so Britain’s best bet may be to crack on with nascent technologies such as hydrogen or carbon capture and storage where no country has yet secured a lead. Investing in those technologies could give the UK “first mover advantage,” says Adam Berman, the deputy director at the industry group Energy UK. “In this industry, if you stand still, you lose.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply