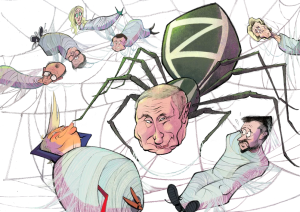

Economic sanctions were meant to be the West’s secret weapon against Russia, a way of crippling Vladimir Putin’s war machine and bringing his invasion of Ukraine to a halt without NATO firing a shot. Instead, Russia’s economy and military remain in rude health. After recent heavy attacks north of Kharkiv, Putin’s troops have seized more than thirty-eight square miles of territory and stretched Kyiv’s already thinly deployed defenses as they grind forward in Donbas. Putin has demoted his long-serving defense minister Sergei Shoigu, replacing him with the little-known economist Andrei Belousov. Appointing a finance specialist as military chief was a reminder that armies march on money. In Russia’s case, oil money.

Remarkably, since February 2022 the Kremlin has defied more than 16,000 separate sanctions imposed by the US and European Union; the destruction of the Nord Stream gas pipeline, which ended Gazprom’s stranglehold on Europe’s energy supplies; and a costly war that will consume up to 8 percent of Russia’s GDP this year. Despite these catastrophes, Russia’s economy is poised to grow at a faster pace than any other G7 nation’s. It’s currently running a budget deficit of just 0.8 percent of GDP, down from 1.9 percent last year. Its overall federal revenues hit a record $320 billion in 2023 and are expected to go even higher in 2024. Those are remarkable figures for a country spending some 40 percent of its state budget on war.

The secret of this remarkable resilience? A shadow fleet of oil tankers registered outside the G7, which has allowed Russia to thumb its nose at western sanctions and to maintain an uninterrupted stream of lucrative oil exports.

Russia produces around 10 million barrels of oil a day and exports half of that, putting it behind the US and Saudi Arabia as an international supplier. That’s far too large a volume for the West to try to ban. Taking that amount of oil off the market would cause an oil price shock and world recession far more dramatic than that of 1973.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]Instead, the West’s response has been to try to depress the Kremlin’s revenues by imposing an oil price cap of $60 a barrel — well below the current market price of $78 — on all Russian oil exports.

The West had hoped to enforce the oil price cap by making it impossible for Russian ships to operate by withholding insurance for them. Some 95 percent of maritime insurance was Western-controlled, mostly based in London. No tanker, regardless of its flag, can dock in port without insurance.

What’s more, no ship engaged in illegal activity — such as sanctions-busting — can be legally insured. The West’s plan, however, came unstuck. The International Group of Protection and Indemnity Clubs’ near-monopoly of the world’s shipping insurance quickly collapsed as India began writing its own policies for tankers, as did Russia’s state-owned insurers Rosgosstrakh and Ingosstrakh. By late summer of the first year of the war, vessels carrying Western-issued insurance fell to under 68 percent of global shipping. Russia’s shadow fleet was born.

The tanker fleet used by Russia is vast and expanding. It grew by 17 percent this year to 787 vessels, according to ship broker BRS (equivalent to nearly 14 percent of the world’s total tanker tonnage). Every one of these ships is, almost certainly, violating international sanctions in the form of the oil price cap. Yet it’s maddeningly hard to verify the real price being paid by Russia’s customers in China, India, Indonesia and Turkey.

There are a host of simple accountancy tricks (known as “attestation fraud”) that can be used to get around the price cap. Oil is typically loaded at a “free on board” price of just under $60 but then sold to customers with extravagant surcharges for transport and insurance that bump the price up to just under the real market value.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]Another legal dodge is for Russian oil companies to sell oil under the price cap to their own subsidiaries in Europe. Lukoil, for instance, still operates major oil refineries in Romania and Bulgaria and has a 45 percent interest in a refinery in the Netherlands. Another common (though illegal) ruse is to pump oil from tanker to tanker at sea, magically transforming the product from Russian crude to something else listed on the other ship’s paperwork. Sweden’s Coast Guard reports that many shadow-fleet vessels are regularly engaging in risky ship-to-ship oil transfers off the eastern coast of the island of Gotland, just outside the twelve-nautical-mile limit which denotes a country’s territorial waters. Sweden is powerless to stop them.

Indeed, international maritime law makes policing the activities of Russia’s shadow fleet almost impossible. A cornerstone of the world’s sea-borne trade is the Right of Innocent Passage, which allows vessels to sail through international waters without harassment, hindrance or inspection as long as they are not engaging in hostile military activity. Whether transiting through the Danish Straits or the Bosporus Strait at the entrance of the Black Sea, tankers cannot legally be stopped. And, again by international maritime law, illegally hindering a country’s merchant shipping constitutes a naval blockade — formally considered an act of war.

Sanctions-enforcers in the US and EU have had to become creative in finding ways to sidestep attestation fraud and the Right of Innocent Passage. On May 1 the Greek navy announced military exercises off the coast of Laconia in the Peloponnese, thereby denying those offshore waters to shadow tankers who often use them to transfer oil at sea.

The EU is exploring ways to use the Baltic Sea Action Plan, a “strategic program of measures and actions for achieving good environmental status of the sea.” It was originally signed in 2007 by all littoral states (including Russia) to introduce environmental spot-inspections at sea. This could be used to end ship-to-ship transfers off Gotland.

The “hostile military activity” clause could also be invoked against Russian ships believed to be engaging in surveillance. According to Swedish Rear Admiral Ewa Skoog Haslum, some Russia-linked tankers in the Baltic have been found to be carrying “antennas and masts that typically do not belong” to merchant vessels. The Swedish navy says it has evidence these vessels are fitted out to pick up signals intelligence — a throwback to Soviet-era “Auxiliary General Intelligence” vessels which used to regularly ply the Baltic during the Cold War.

Lastly, the US Office of Foreign Assets Control has begun the painstaking process of imposing sanctions on individual ships suspected of sanctions-busting. According to ongoing monitoring by the Kyiv School of Economics, the US has successfully sanctioned forty-one vessels. But these have been almost instantly replaced with thirty-five new tankers Russia has added to its shadow tanker fleet since December.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]None of these measures is likely to put a serious dent in Russia’s continued ability to export its oil. Around 46 percent of Russian oil is still carried legally in western-insured ships with the supposedly correct paperwork. And that’s not even counting exports of Russian liquefied natural gas, or LNG, which is not yet subject to any sanctions at all, for the simple reason that Europe remains dependent on Russia for a significant chunk of its LNG supplies. Despite the EU’s goal to become independent of all Russian energy by 2027, Spain and Belgium are currently the second- and third-biggest buyers of Russian LNG respectively, just behind China.

The EU says it’s working to limit imports of Russian LNG as part of its latest package of sanctions. But as Kadri Simson, the European commissioner for energy, admitted earlier this month, Europe will need more, not less, LNG in 2025. That’s because Russia continues to supply some 8 percent of Europe’s piped natural gas.

Most of this gas transitions through Ukraine into Slovakia. Despite the war, in 2023 Gazprom paid Ukraine $800 million in transit fees (about 0.46 percent of Ukraine’s GDP). But those transit contracts between Ukraine and Moscow are due to expire at the end of this year, forcing Europe to replace yet more of its natural gas with LNG.

Since the beginning of this year, Ukrainian drone strikes against refineries in Russia have taken out around 15 percent of Russia’s oil refinery capacity. But this has had the paradoxical effect of forcing Moscow to export more of its crude oil due to a lack of storage capacity. Russian seaborne oil exports rose by 4 percent in March, driven by a 12 percent increase in crude oil shipments (around 400,000 barrels a day) while exports of refined oil products declined by 6 percent.

Most of that extra oil has headed to European forecourts after India refined and re- exported it. “In Europe we’re still buying Russian crude, except it’s been refined in China and India, so all you’ve done is add a four-month sea journey to the crude that we used to refine here in Europe much cheaper, and all the extra costs are being inflicted here,” says Ben Aris, editor-in-chief of bne IntelliNews, a Berlin-based analyst. “The irony is that the sanctions are just [market] distortions which are actually helping the Russian government.”

“We have this weird sort of compromise where we negotiate with ourselves into a situation which allows the Russians to completely cheat,” says Bill Browder, a sanctions activist and CEO of Hermitage Capital Management. “They bought a whole bunch of tankers. Those tankers are moving the oil, and the Indians and the Chinese and the Indonesians are very happy to get that oil.”

But blaming sanctions-busting customers is too easy. The real reason Russia can afford to continue funding its aggression in Ukraine is that Europe and the US refuse to contemplate the economic pain of a real blockade of Russian crude. Europe also claims to stand behind Kyiv yet continues to import, either directly or indirectly, huge quantities of Russia’s oil and gas, putting more than half a billion dollars a day into the Kremlin’s coffers.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]“We are a united and great people and together we will overcome all obstacles,” Putin said during his May inaugural address. What he meant was that Russia controls a great and valuable resource that the world can’t do without — even if that oil reeks of blood.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply