Marie-Georges-Jean Méliès made more than 500 films in his career, but 1896 was a banner year for the Frenchman. He captivated audiences with Playing Cards, his sixty-seven-second exploration of three cigar-puffing men as they are waited on by two young ladies. One man reads the paper and pours the wine as the other two play cards. It was the first reboot in film history. One year earlier, Louis Lumière released Card Game, a forty-three-second exploration of three men with cigars drinking wine and playing cards as they are waited on by a man. Méliès rightly recognized the original’s lack of representation, not to mention the absence of a news- paper.

For all the talk of the creative dead ends in twenty-first-century filmmaking — the endless parade of reboots, adaptations and superheroes — it is worth noting that filmmakers have always been cannibals and strip miners. Playing Cards debuted the same year F. Scott Fitzgerald was born — his most well-known work, The Great Gatsby, has been adapted to film four times, with an animated version in the works. But what’s changed about Hollywood in recent years isn’t the instinct to take safe bets on already popular content — it’s that those bets are no longer paying off.

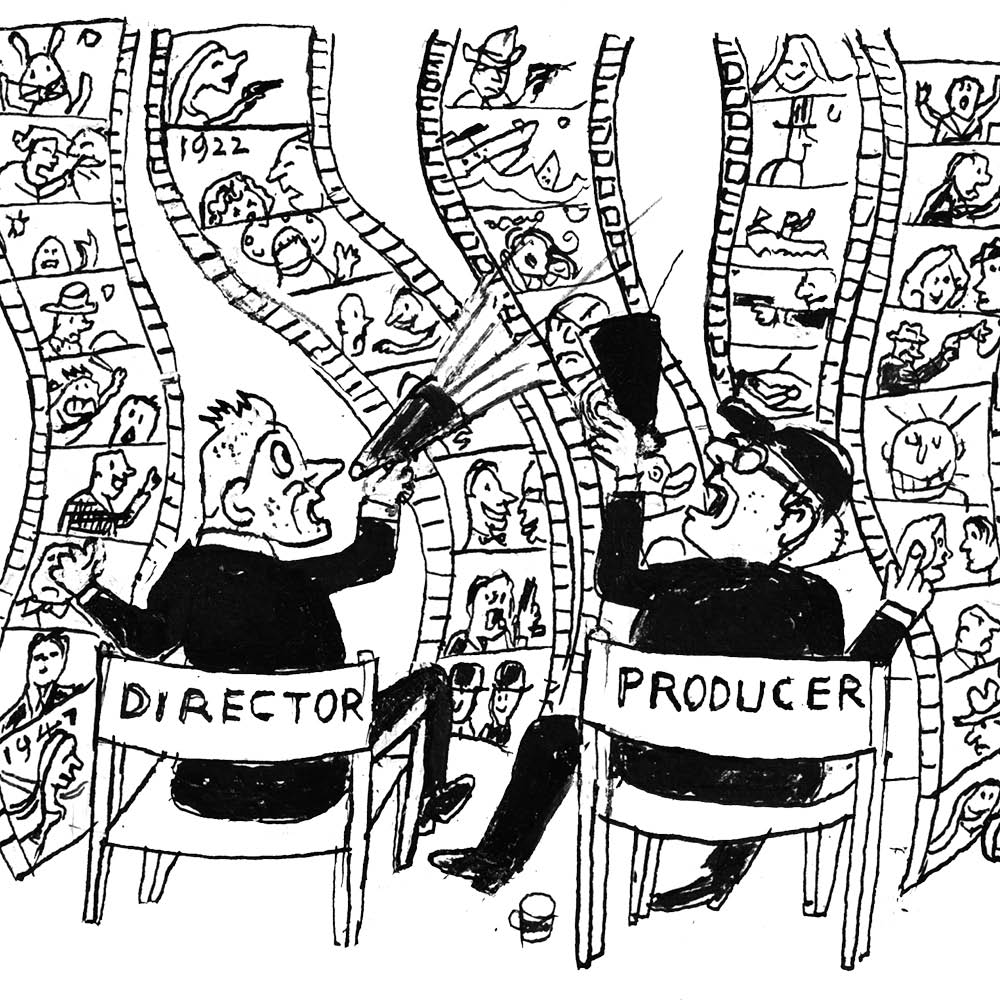

Author Bret Easton Ellis is no stranger to the adaptation. Film versions of his novels Less Than Zero and American Psycho are already cult classics among film nerds, so it is only natural that HBO is developing his 2023 book The Shards into a limited series. He has only been to the movies twice in 2024. He blames the pandemic for shuttering the movie theaters he once frequented. “The big decisions are made by the marketing department on what movies get made. It’s not like some fiery passionate producers stomping in or whatever. It’s, it’s like, you know, IP and sequels and animated stuff,” he tells The Spectator. “No one cares about interesting.”

If you can’t be interesting, you can at least be profitable. But formerly safe intellectual properties have been sinking at the box office lately. Even before Disney started hemorrhaging money on formerly reliable Marvel movies and Warner Bros. lost its shirt on DC Comics in the aftermath of the pandemic, Hollywood witnessed the implosion of the reboot, according to Brett Dasovic, host of the podcast Pop Culture Crisis. “For a film to be profitable it needs to at least double the money at the box office,” Dasovic says, which is why studios spent hundreds of millions of dollars on 2016’s Ghostbusters, 2017’s The Mummy, 2018’s Tomb Raider, 2021’s West Side Story and 2021’s The Matrix Resurrections, all of which followed earlier “versions that were either box-office successful or highly appreciated by fans or critics.” Matrix Resurrections, for example, grossed only $159 million worldwide on a $190 million budget. The original Matrix grossed approximately $460 million with a $63 million budget.

The reboot of today is not so much about elevating the previous telling of a story; it’s more like Ed Gein digging up existing IP and parading around in its skin. While spinoffs and sequels have long been done in the name of fan service, Emmy-winning actress Drea de Matteo says the industry is instead demanding that the audience conform to the mores of marketing departments.

“Everything is being repurposed. There’s no originality,” she says. “We’re not breeding critical thinkers. We’re breeding people that are going to conform to the Netflix agenda.”

Hollywood is not going to change its ways, only the targets of its strip mining. Stan Lee and his comic books may no longer be as fashionable as they were when Robert Downey Jr. donned the Iron Man costume and the Avengers first assembled, so studio execs — and critics for that matter — are turning their attention to video games. The Last of Us is getting the kind of accolades once reserved for Joss Whedon’s cape-and-costume action comedies. Super Mario Bros., dripping with nostalgia and meta humor, earned $1.36 billion at the box office — double that of the second-place Pokemon Detective Pikachu.

The very first video-game adaptation was the live action Super Mario Bros., which went on to critical and box office failure and served as a warning shot against the genre. That was in 1993. America had just elected a hip boomer president with sunglasses and a saxophone, the Soviet Union was no more, history had just ended. There was no time for a nostalgia economy, particularly for a property that had only been around for eight years. Hollywood was in a creative mood with Pulp Fiction, The Lion King and Forrest Gump in the works. Even their adaptations and reboots of the era broke new ground. The two highest-grossing films of 1993 were Spielberg’s breathtaking world-building in Jurassic Park and The Fugitive, a taut and unapologetically adult re-imaging of the 1960s series, which had veered into elaborate melodrama to keep the hunt going for 120 episodes. You can look at either film and witness a Hollywood that sought to elevate its subjects, rather than infantilize them with 180 minutes of film shot entirely in front of a green screen and dialogue copied and pasted directly from HR seminars.

America today is hardly in the mood for the end of history triumphalism of the Clinton years; the malaise of the 1970s rings truer with its wars, economic despair and collapsing cities. At least suffering can yield great art, which could be why film buffs, Ellis included, consider the 1970s the high point of creativity in moviemaking. 1969 saw the arrival of Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid, Midnight Cowboy and Easy Rider alone. “I think the only person who survives is Jon Voight. I mean, everyone else dies at the end of all three of these blockbuster films, and audiences love it… I don’t know if there’s that audience for those kinds of movies anymore,” Ellis says. The millennial audience is instead fed talking cats, talking dolls, talking hedgehogs from the cartoon strips and video games of their youth — whether they have children or, increasingly, not.

Creativity and innovation are alive and well in Hollywood, though. They can still be found in the accounting department, which is delivering fresh takes on the genre of austerity. Gone are the days of merely shifting production costs onto subsidiaries or claiming expenses from flops to make it appear as though Return of the Jedi or Mean Girls never turned a profit. Accounting departments today are shelving completed films, having calculated that they would make more money buried in the vault as tax write-offs than they would if released for public consumption. Warner Bros. has been at the cutting edge, turning its backlot into a veritable Skid Row just like the rest of LA. You imagine execs warming themselves next to barrel fires filled with the “unreleasable” Batgirl, the money pit of Scoob! Holiday Haunt and an adaptation of the New Yorker short story, Coyote vs. Acme. The studio sank a reported $200 million into those three films alone, but they’re just the best-known casualties of the newest iteration of Hollywood accounting. Warner Bros. claimed $115 million in write-offs in third quarter filings in 2023 — that kind of money will come in handy as the studio pursues Paramount.

In June 2024, Paramount told employees in a town hall that it plans to slash $500 million in spending after suffering a 61 percent drop in profitability over the past five years. Such austerity may look like failure to laymen, but you get the sense that it was an advertisement for suitors. Rumors of a Warner Bros. acquisition of its one-time rival fell apart in the spring, but the romance was rekindled shortly after anonymous sources went public about the sinister town hall.

The write-offs don’t portend a sudden resurgence in original content. “More and more, there’s going to be concerts, I think. Taylor Swift proved with the Eras Tour movie that that is a very viable way to make a lot of money and to get butts in seats,” Ellis says. “Now, that is true with Taylor Swift. But I imagine Beyoncé could probably do that. And I’m sure there’s going to be a lot of acts that are going to be doing that.” Outsourcing production costs to exist- ing concert venues and performers can only go so far. Execs will want more. The recent Hollywood strikes centered on streaming-revenue sharing, but no one doubts the role that ChatGPT played in the shutdown. In April, a British company announced plans to debut the first-ever film written entirely by AI. The June screening of the film, The Last Screenwriter, was postponed by public backlash.

Dead Internet Theory holds that the entire internet is made up mostly of bots talking to bots. Humans are outnumbered. AI script writers will happen. “They” will become the new digital version of a human centipede and anything any of us has ever said on the internet will be absorbed and regurgitated by the AI screenwriters of the not-so-distant future. Scripts written by algorithmic robots will be transformed into AI video and then pumped into the microchips stitched into brains across the world — where you can “watch” the new six-hour Tarantino film in under two minutes — though the speed at which you digest may vary.

Artificial moviemaking will expand into the relationship between the movie stars and the audience. If everybody nowadays has the ability to be a critic, soon they may be able to insert themselves into movies. Movies could become choose-your-own adventures. The entire idea of a film will be deconstructed. And it won’t end there.

Drea de Matteo told me she was recently approached by an AI dating site. “These guys online would think that they’re dating me. They can put my AI avatar in Monte Carlo or Britain. They can say, ‘I want her in a red dress.’ I can be in five places at once, my avatar, dating all these different men.” She passed.

There will be AI-generated movies with AI-generated audiences with AI-generated advertisements and this will be a feedback loop — a test tube for sentient art that some digital passersby can walk through a two-way mirror into a dystopian nightmare. “At the end of the day,” de Matteo says, “the AI stuff’s never going to have that level of real heart and soul.”

But then, neither does anything coming out of the studios which look to their marketing and accounting departments for salvation. Barbie and Oppenheimer may have dominated 2023, but the top ten box office draws as of June 2024 include eight sequels, reboots, or reboot-sequels, one animated flop and a music documentary.

Even if Hollywood is dead, it’s still got enough smoke and mirrors to create the illusion of life, even if it comes out as Weekend at Bernie’s. If you look closely, you’ll see the fishing line attached to the arms. At least until the AI is ready to pass the Turing Test.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply