The beautiful muse to great male artists is a tricky figure, omnipresent in history but a bad fit for our fussy time. From Edie Sedgwick to Zelda Fitzgerald, and even some male ones, such as Neal Cassady, they’ve always been part of artistic scenes. In the scene of great Sixties rock, one of the most important was Jenny Boyd. She may not be as well-known as Yoko Ono, or her sister Pattie, who was married to George Harrison. But she may have been as influential. She was in the backstages, the bedrooms and the jam sessions with some of the most iconic musicians of all time. Shortly after traveling around India with the Beatles, she married (then divorced and remarried) Mick Fleetwood. Later, Donovan would write a love-sick song about her, “Jennifer Jupiter.” So would Mick Jagger.

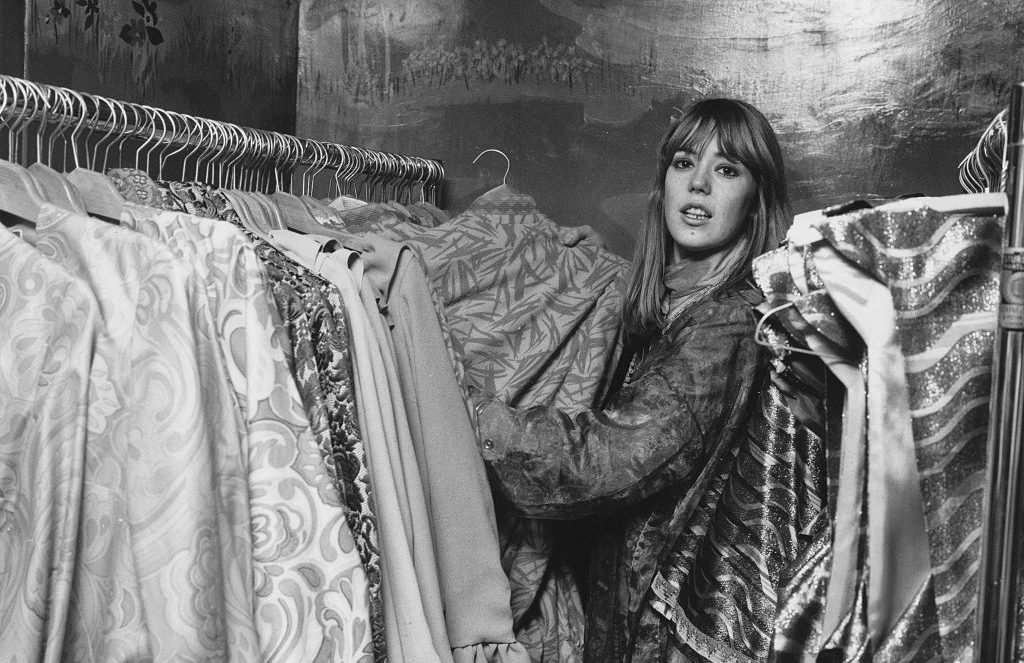

It’s no surprise that Jenny Boyd became a muse to these legends. Doe-eyed, with blonde hair and never-ending legs, she got her first modeling job at seventeen. “Modeling then was new and fresh,” Boyd told me. “The photographers were all young and fun. This was before the days when it started to get sleazy.” Jenny and her sister Pattie had what she described as “just the right look for the time,” and modeled the clothes of Foale and Tuffin, the quintessential dress of the Swinging London scene.

But Jenny wasn’t cut out for modeling; in her own words it “just wasn’t for her,” so as she became more notable, she played around with it. “In New York, I was surrounded by seasoned models. I wasn’t one, and I was really short-sighted. We had to get on runways in front of all the press and masses of people. I couldn’t even see the end of the runway because I couldn’t work out which bit was the stage still and what was the floor. I vowed to myself I would never do another catwalk again.” But when she was inevitably asked to return to the runway, she decided to dance down it. “It was on a platform in Belgium. The music was great, so I just danced, and then I got known for doing that.”

A life intertwined with great art and artists started after her sister married Harrison in 1966. Two years later, Boyd bagged herself a front row seat to the most influential band of all time. The then-teen Boyd got to know the Beatles, and she became a regular in the scene with what is still, to this day, the most iconic set of musicians ever to have worked. Looking back, it feels like something real happened then that perhaps today even the best stars only mimic, “Having spoken to young musicians lately, I’ve learned that most of them don’t even write their own songs. It’s not like it was back then when I’d watch John come up with an idea and then the rest would join in,” Boyd told me, referring to John Lennon over a long conversation about the past, present, and future of creative life and the people around it.

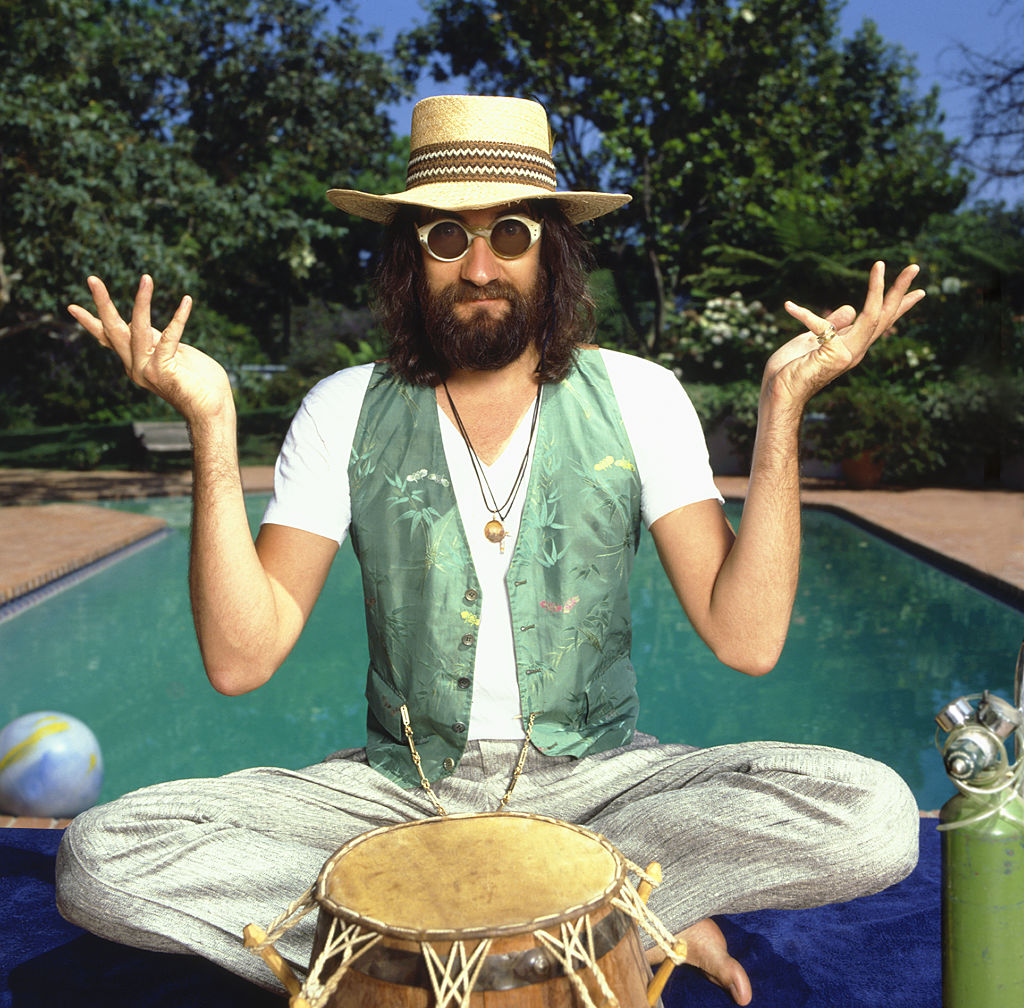

Dancing around the world in designer dresses accompanying the world’s most famous artists and rock stars may sound like a pipe dream. But in Boyd’s memoir, Jennifer Juniper: A Journey Beyond the Muse, you realize that this fanciful life isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. Speaking to the Guardian about her marriage to Mick Fleetwood, Boyd said, “If you’re going to be with someone who’s clearly an artist, who’s deeply dedicated to what they do, then you need something that you’re passionate about. Otherwise, you’re just an extension of someone else’s dream. Sadly, I never felt I was creative. I felt so locked inside.” Plagued with addiction and fame and heartache, their relationship was more off than on. In 1977, Jenny reunited with Mick in LA in order to give their relationship one more shot. “There’s something I ought to tell you,” Mick said when they got there. “I’ve been having an affair with Stevie [his Fleetwood Mac bandmate Stevie Nicks] for the last few months, since we were in Australia.’’

“At first I didn’t understand what he’d said,” Jenny writes in her memoir. “It took some seconds for it to sink in. I stared at him in silence, feeling as though I’d been kicked in the stomach; my mind and heart in complete turmoil as I struggled to make sense of his words.”

Completing her memoir took years. “When I first started writing it, I didn’t even think I was going to write a book,” she told me. “In the evenings I would write things that I remembered from childhood and different parts of my life. And it just grew.” When everything was down on paper, Jenny decided that the safest thing to do was to label the book as “a very thinly disguised fiction,” so as not to upset anybody in it.

“I kept thinking to myself, ‘oh God, do I really want to go through with writing a memoir?’ Then I decided that I was going to do it. This is what I needed to say. The feedback was great. Mick obviously features in a lot, and he had written a book before, but he got his facts wrong. Then when he wrote another one, many years later. I said to him, ‘we’ll get your facts, right, I’ll help you if you like.’”

On the cover of Jenny’s memoir is an endorsement from Mick: “The beautifully poignant story of a partner, mother, friend and truly inspirational woman.”

Rather than straining the relationships with those who feature in the book, Boyd says the memoir and the journey leading up to it strengthened them. Boyd had moved from LA to London and was working for an addiction treatment center. After completing an MA in Counseling Psychology, she set up her own company, Spring Workshops, through which she brought therapists from the US to the UK to help addicts.

“When I got into therapy and the addiction field in LA and started really looking at my life, I started to look at what they call codependency and realize that, actually, my relationship with Pattie has been very codependent, as well as with Mick. But we were young, we had rather sort of a crazy upbringing. And the two of us children really stuck together, you know, for each other.” With Mick, Boyd says “we have a real deep love for each other. That means that we don’t need to be connecting or contacting each other all the time. I saw him earlier this year with my husband and we have such a good friendship. And then with Patti, too, I saw her last night, and after all these years, now it’s just more grown up.”

The last thing I asked Boyd was for her thoughts on modern music. She’s currently updating her book, Musicians In Tune, in which she interviewed seventy-five contemporary artists about their creative process. “It’s a whole different scene,” she said. “It’s all about Spotify and how many people are following you on social media. I don’t think people really have muses anymore. Maybe they do, but certainly not like they did.” If anyone would know the real deal when she sees it, it’s Boyd.