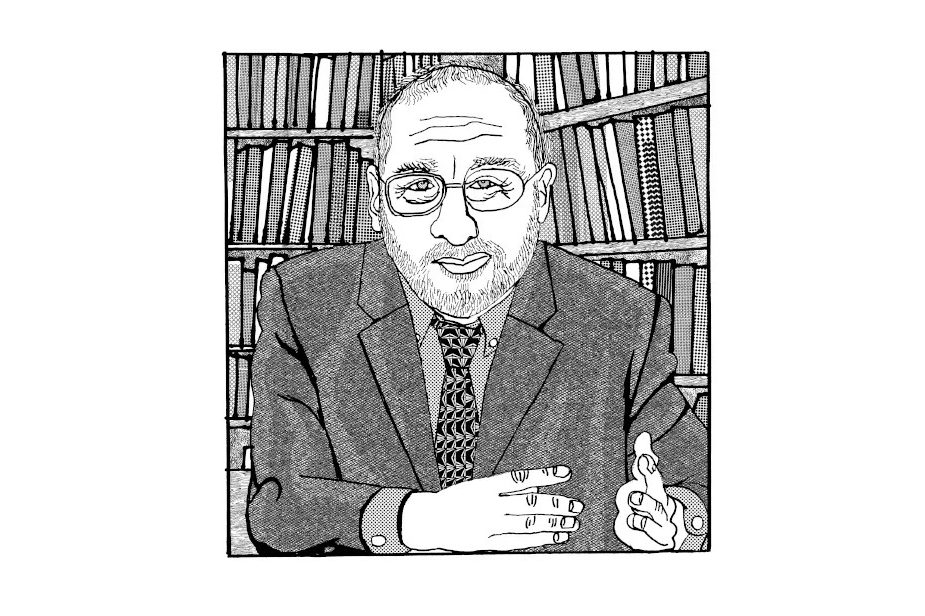

When Joseph Stiglitz talks, the left listens. The Nobel laureate has advised multiple Democratic presidents and the World Bank, where he worked as chief economist and senior vice president. He’s long been a leading critic of the liberal leanings that have dominated the West’s economic policy for four decades. So when we meet in The Spectator’s London office, I ask him if Britain’s Labour Party has sought his advice. It wouldn’t be unthinkable.

“I just met with, in a TV show, one of the Labour shadow ministers. We had a good discussion,” he says, smiling. But the New Keynesian economist is in the UK for four days, and his new book, The Road to Freedom, is keeping him busy. No summits on “securonomics” this time.

The aim of the book is to reclaim the word “freedom” from the economic right, which Stiglitz believes has forgotten about trade-offs. The book’s thesis is that “one person’s freedom can often amount to another person’s unfreedom.” Once you accept this premise, the Columbia professor argues, the case for “coercion” — and a bigger state — becomes much more palatable.

‘The idea was that if you lift up the top, everybody would benefit. That clearly didn’t work’

“Traffic lights are a kind of coercion,” Stiglitz, eighty-one, says. “In a place like New York or London, if you didn’t have traffic lights, you would have gridlock and you couldn’t go anyway. So by having this little coercion that you’re not allowed to go, everybody has more freedom.” It’s the same example he uses at the start of his book: a “metaphor,” he says, for how in “lots of other areas where if we co-operate, we expand what we can do.”

It’s a curious critique, not least because free-market economics is about voluntary co-operation (Adam Smith’s butcher and baker famously come together, voluntarily and out of their own interest, to make the world spin round). But what’s notable is what’s lacking: any kind of credit given to the achievements of the free enterprise system. The unprecedented fall in world poverty in the past twenty years, the decade added to life expectancy in the past thirty years: are these signs that economic liberalism has failed?

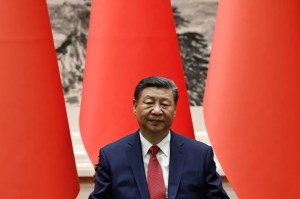

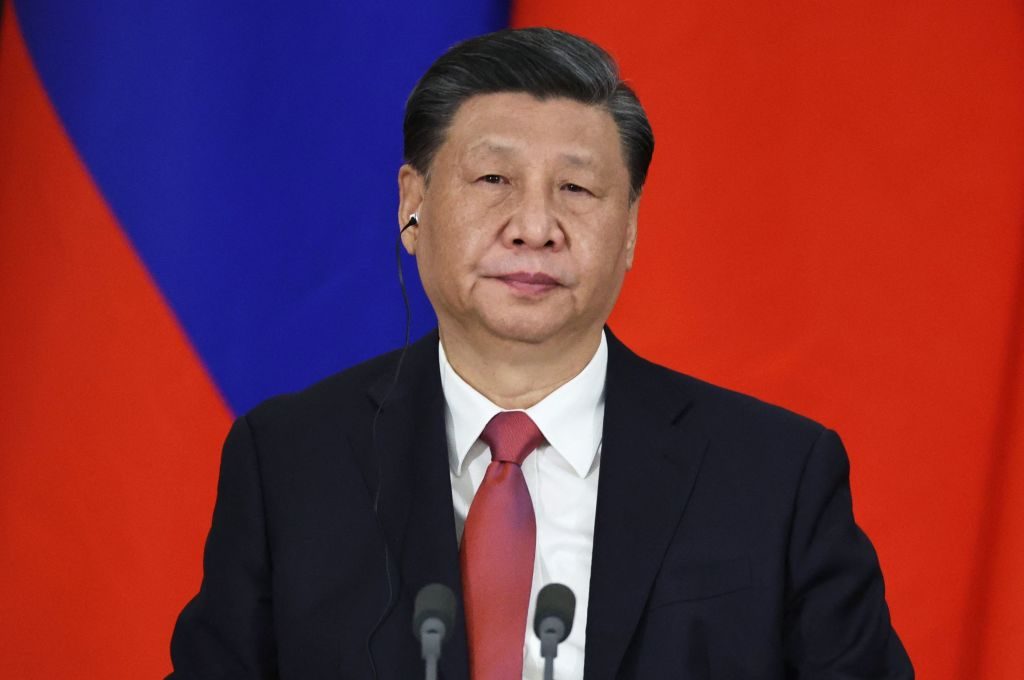

“I think it has,” Stiglitz says. “A lot of the reduction in poverty globally occurred in China, and China didn’t follow the neoliberal doctrines.” It was “on their own terms, which included capital controls, strong industrial policies, a lot of policies that were the antithesis of neoliberalism.”

Strip out China, however, and the fall in world poverty in recent decades is still extraordinary. But it’s the inequality, especially in western countries, that Stiglitz takes issue with. “The benefits of growth that occurred went to the top; the middle and the bottom stagnated and some of them even went down. Trickle-down economics didn’t work: the idea was that if you lift up the top, everybody would benefit. That clearly didn’t work.”

His dismissal of “trickle-down economics” reminds me of a passage in his book. “Many on the right,” he writes, “would claim that such taxation — even with representation — is tyranny.” What serious politician or economic thinker says this? “The extremists on the right,” he responds, “in the House of Representatives, in the Republican Party, call themselves the Freedom Caucus, and they’ve been advocating a reduction of taxes.” They want tax cuts, but is that the same as saying tax is tyranny? “I’m not saying that anybody said that all taxation is tyranny,” he concedes.

Like “trickle-down economics,” the idea that tax is tyranny seems to be a phrase that’s attributed to right-wing thinkers rather than advocated by them. Still, this group is the biggest bogeyman in The Road to Freedom. It seems like the left’s response to “the blob:” “the right’ is a term he uses to encompass every political philosophy that might have reservations about an ever-growing state. Anarchists are lumped in with One-Nation Tories; classical liberals, neoliberals, libertarians, social conservatives, liberal conservatives and even centrists are described as if they are one homogeneous bloc.

“When you write a book you want to achieve some clarity,” he says, “and that [out] of necessity entails some simplification. I try to highlight, maybe too much in footnotes and less in text, some of the complexity of these and the fact that there are divisions among what I call ‘the right’ on these issues. But I think the broad landscape that I try to paint [is] that neoliberalism… was about deregulating, about lowering taxes.”

What’s the alternative he’s proposing? “Progressive capitalism” is his answer: “something along the lines of a rejuvenated European social democracy… a twenty-first-century version of social democracy or of a Scandinavian welfare state.”

And what, specifically, does he think Sweden, Denmark or Norway do differently that countries like America should emulate? “What I admire is how they have gone to try to create a more inclusive society,” Stiglitz says. “Investments in children, investments in preschool education, social protection… they were much more aware of the need to have active labor market policies and social protection to make it politically acceptable and to get efficient use of the labor force so that they don’t remain underemployed. We in the United States didn’t do that.”

But are these countries rejecting what he calls “neoliberalism” or simply using the fruits of capitalism slightly differently? Sweden has no formalized minimum wage and has abolished inheritance tax. Its education is indeed world-renowned, but it allows profit–seeking independent schools in the state sector. The Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom ranks Denmark, Sweden and Norway the seventh, ninth and tenth most free countries, respectively. The United States comes twenty-fifth on the list.

Is Scandinavia really a good example of a rejection of market policies? “When I was writing the book, I was sensitive to all the things you [are] saying. They haven’t fully adopted the policies I would have advocated,” he says. “Norway has a very active industrial policy and part of the doctrines of neoliberalism is that government shouldn’t be directing the economy. The government effectively owns the most important industry, Statoil, or Equinor as it is called today… Sweden has a very high carbon tax, so they are intervening in the market. It’s not a free-for-all.”

What makes Stiglitz so convinced that a bigger state will lead to the outcomes he desires? Surely the bigger state could lead to a Chinese-style autocracy rather than to a Swedish utopia? What happens if you grow the size and powers of the state, and then hand that over to somebody like Donald Trump?

He suddenly turns very serious. “I worry about everything you said,” he says. “Anybody who’s been through a Trump administration worries about what you exactly said. It could go the other way. But on the other hand, if we don’t do enough for ordinary citizens there is going to be a backlash.”

A more interventionist state, he says, is how you avoid electing Trump in the first place. “We won’t achieve that inclusive society without more government action.” It’s about how to “deal with the dangers that you present: money in politics, transparency, trying to build institutions, checks and balances within government and within our society. All human institutions are fallible and we have to recognize that. I’m not Pollyanna on this, I recognize the dangers, but I recognize even more the dangers of not doing enough.”

Stiglitz suggests that communism and Reagan-Thatcherism are at opposite ends of the spectrums more than once in his book. “Communism went too far in one direction,” he writes, “Reagan-Thatcherism went too far in the other.” Does he really think this is a fair and equal comparison? “I never said they were equal and opposite,” he says. “But they were at the end of the spectrum that we’ve experienced… We could go further. I don’t know where [Javier] Milei is going to go in Argentina. He may go further than Reagan and Thatcher.”

Maybe so, but is it really possible to compare liberal supply-side reforms with a system that killed an estimated 100 million people? “We haven’t seen yet, fortunately, where this could go,” Stiglitz says. “We know where fascism led last time.” So Thatcherism is fascism? “I think we’re on that road, yes I do,” he says. “But we aren’t there. The book is written because I wanted people to be aware of the road that we were on.”

Is it possible that we’re “not there yet” because the Thatcher-Reagan path is not an extension of fascism but its antithesis? Like communism, fascism led to atrocities, while neoliberalism led to unprecedented prosperity? “The fact is that, in the advanced countries, neoliberalism failed,” he says. “Growth slowed, and what growth occurred went to the top and that has provided the fertile field for populism and given rise to Trumpism.”

It’s not just America where Stiglitz wants more to be done. The Labour Party may not (yet) be formally asking for his advice, but he has some to offer anyway: “Take stronger actions than you’ve promised so far… if you borrow money for good investments and you persuade the market that you are actually using that money… if you were a firm and you get returns well in excess of what your cost of capital [is], it makes the firm balance sheet go up and it makes them better off. And the same is true for a country.”

This was the gamble made by a recent prime minister who went further than she promised and thought the markets would respond well to her massive borrowing request. But Liz Truss’s problem, he says, was that “borrowing for an unfunded tax cut is, especially for the top, not a good investment.” Of course she was also borrowing for what, at the time, was thought to be a $125 billion energy subsidy — a glitch Stiglitz attributes to a “poor regulatory system for energy pricing.”

His advice, in short, is that Labour should break free of neoliberal notions like the need to balance the books; to continue on the path of the past four decades is to fall behind the times. The United States “is moving away from neoliberalism,” he says, “and I would say the whole world [too].” His comments certainly feel on trend, as the pandemic ushered in a new era of growing government. But at what cost will these changes come?

Watch the interview on Spectator TV:

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply