The first time I took LSD was alone on Christmas Day in a snowed-in Montana cabin. I watched my skin crawl and the walls melt. It was the first time since childhood I didn’t hate my own body, and a nice break from the depressing bioethics I was studying in school. I took deep breaths and stretched. As the effects took hold, I watched illustrations fly out from a gorgeous, tattered copy of Mark Twain’s biography of Joan of Arc.

Four hours later, after smoking an entire pack of cigarettes, I was convinced I was descending to hell. I watched fake flames lick the yellow wallpaper. It was miserable and listening to Nick Cave didn’t help.

At dinner with friends later that night, the elk roast resembled human meat and the bread rolls made to commemorate St. Lucy (who had her eyes gouged out) seemed more than appropriate for what I was experiencing. I couldn’t eat — I just sat and smoked more cigarettes. Afterwards, I watched Jean-Luc Godard’s Vivre Sa Vie. I sobbed at the scene when Anna Karina, playing a lowly soon-to-be French strumpet (still a holy child of God), weeps alone during a midnight screening of The Passion of Joan of Arc. We were both searching for some profound redemption that was impossible to find by ourselves.

The deep morbidity of my first drug experience reflected my mindset: someone grasping for spiritual straws, slightly nihilistic, divorced from family and studying analytic philosophy. By some quiet miracle, the horrors of my acid Christmas somehow induced what William James refers to as the religious experience: a feeling of oneness with divine, creative force. I was temporarily overwhelmed by a wave of unbearable compassion, forgiveness and surrender.

My Christmas trip set off a search for psychic salvation. I began taking psychedelics routinely, ultimately led to finding solace in the teachings of Jesus. Certainly, psychedelics have brought me closer to God.

I will always credit much of my spiritual and personal development to my time with the “classical psychedelics”: tobacco, cannabis, LSD (always drops, with the exception of some great Owsley Altoids in upstate New York), psilocybin, peyote (my personal favorite), DMT, ayahuasca. I love these substances. In some ways I maintain an almost utopian attitude regarding the promise of them (especially psilocybin) to facilitate positive psychic change.

Historically, many of these substances were used as divinatory tools. That fact is inarguable at this point. They may not be “the cause” of religious experiences and conversion, but they can be effective agents to facilitate them. Studies and plenty of anecdotal reports support the theory that they can be tremendously efficient in facilitating ego-death and the feeling of oneness with the universe.

The quantity of psychedelics seems to matter less than the mind of the user. I know people fond of taking heroic doses of psilocybin or LSD and doing all sorts of stupid shit, with no apparent psychic reward other than the momentary rush such a high affords. Many of us who truly believe in the power of psychedelics to change human thought remain cynical and undeniably miserable after the trip is over. We are all innocent hypocrites, but there has to be somewhere for the mind to go when we are not on drugs. For me that was Christianity.

I have since formally converted to Greek Orthodox Christianity, although I firmly believe that all God’s children are saved — and, ironically enough, I reject the sacraments as necessary to experiencing God (a truly heretical belief for many Christians). But I find tremendous psychic reward through loving Christ and the uniquely human challenge of participating in a church community. Orthodoxy is wonderful because it embraces the “great mystery,” reminding us that God is an experience of pure love. You can have this with or without mushrooms, of course.

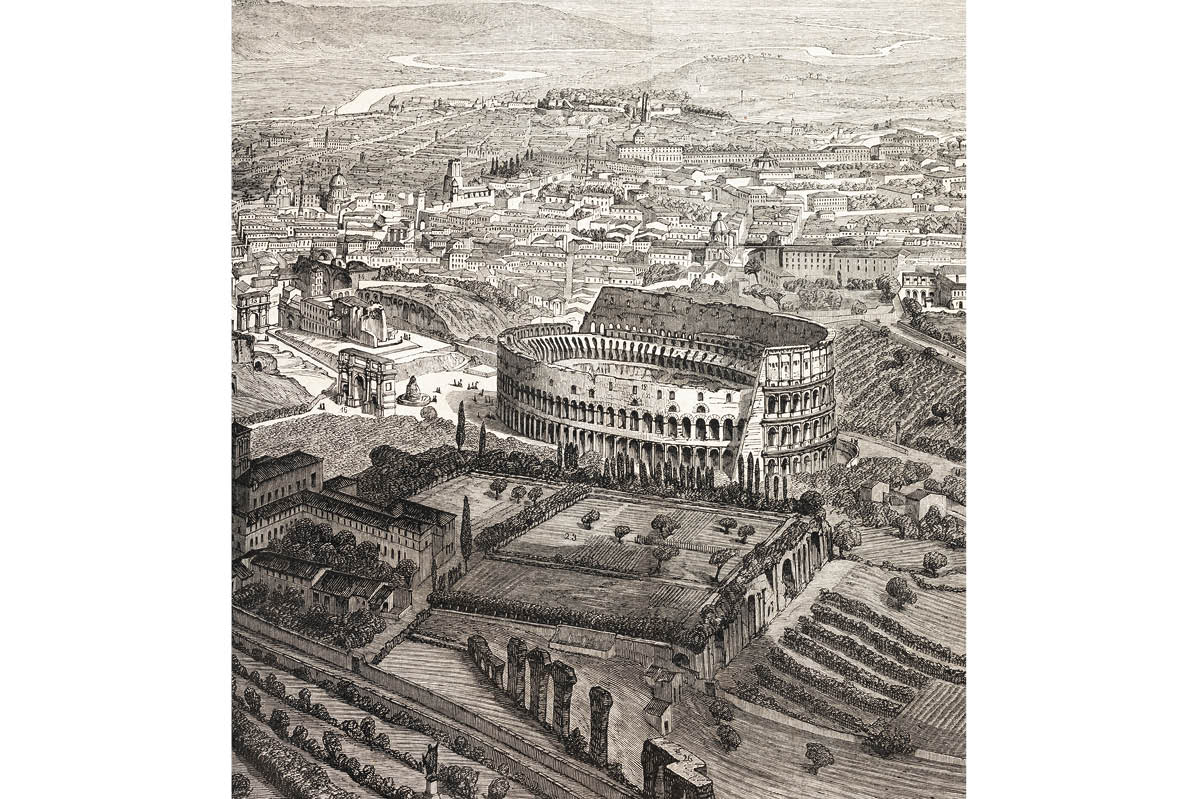

I have taken large doses of LSD under a flurry of ideal and not-so-ideal conditions. There was a honeymoon hiking trip to Death Valley during the 2016 spring super bloom of wildflowers and rattlesnakes. Two months after seeing God in California I took LSD in Paris and witnessed an especially brutish group of tourists at the Louvre shapeshift into a sea of angry Homer Simpsons, fighting for photos and yelling out of what I perceived was total ignorance of the art surrounding them. I was literally in hell, standing silently before Ingres’s Jeanne d’Arc au sacre du roi Charles VII for twenty minutes in order to convince myself that I would not be carried out of the museum in a straitjacket. This was also years before I came to realize what a truly fucked-up genius Ingres was.

After fleeing to the prayer area of Notre-Dame in a psychedelic psychosis, I sobbed uncontrollably as I witnessed angels moving across stained glass while more tourists shoved each other for selfies. I was overwhelmed by a wave of unbearable compassion, surrender and forgiveness; I forgave myself and everyone around me for our misdeeds. Instead of attacking people for failing to understand what I experienced, I decided to devote my life to the creation of challenging, compassionate art. I survived the trip, left the church and became a painter shortly after.

Of course, there are the dark sides to drug use outside of its potential for being a lifeline to God. Many people’s psychedelic attitude is more Moby-Dick than the Bible: a futile chase for the enigmatic, indescribable experience of Truth and Progress by a ship of destructive, hubristic (and mostly male) fools. A short internet anthropology of drug-forum commenters and popular drug figures should be a reminder enough that these substances don’t guarantee enlightenment. Let’s be skeptical of any cultural revolution that counts Timothy Leary as one of its proudest philosophers.

I can talk about these substances democratizing a variety of individual religious experiences, but they can only take you so far. I see a nation of young people sitting in front of screens, interacting with their own drug-induced images rather than each other, experiencing loneliness and thus needing more drugs to numb their pain. The world doesn’t consider the drug-like qualities of endlessly doomscrolling through Twitter or Instagram, or two-day free shipping cooling snail jelly under-eye masks you don’t need from Amazon. The more addictive distractions get, the emptier it’s going to be.

Like Albert Hofmann, I believe in the potential of psychedelics to reconnect us with the natural world around us. I’ve drawn Datura stramonium plants on LSD in the Oxford University botanical garden, believing fully that I could communicate with flowers and fruit. Four years ago, while camping by the Boulder River in Paradise Valley, Montana, I witnessed a conference of plants and bats whispering about John Milton after I ate five or six grams of Psilocybe cubensis, and the stars spelled out “SICK.”

For many, the most important psychological growth associated with psychedelic use is what happens after the transitory moment of pneumatic bliss has passed. My most formative psychedelic experience did not involve anything I’d taken, but was assisting a friend who gave birth out of hospital. Witnessing her birth, I was struck by the simultaneous explosion of violence, blood and, above all else, love it took to bring life into the world, without the use of drugs. I saw that a successful birth requires the same ego-death and psychic surrender promised by the psychedelic substances available to us. It was literally miraculous.

After the labor, I assisted the midwife in cleaning up and examined the alizarin-colored placenta for abnormalities. Had something gone wrong with the delivery of the placenta, such as post-partum hemorrhage, the midwife would have injected ergometrine to restrict uterine bleeding, an ergot-alkaloid brought into this world by none other than the “father” of LSD, Hofmann himself, a drug that has saved the lives of countless women since its discovery in 1932.

The last time I took LSD was over a year ago in Escalante, Utah. The red rocks swirled like marbled Italian bookmaking paper and the vast canyons folded me into the landscape like pink cake batter. I remembered that Albert Hoffman had his first mystical experience as a child in Germany, hiking in the mountains while totally sober. I was very much at peace with the idea of dying there in the canyon that day. I didn’t feel the need to do psychedelics again for a long time.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2022 World edition.