Last summer, I spent some time in and about Port-en-Bessin-Huppain in Normandy. The little fishing village and its surrounding towns on the English Channel (“La Manche,” “the sleeve” en français) is delightfully picturesque in that rugged, elemental way that proceeds from the collision of tempestuous sea and commanding headland.

Expansive fields of corn and other crops ripened fast, orderly in their serried, midsummer ranks. Orange-red poppies punctuated the grassy, flower-strewn verge and complicated the landscape, heavy with age and history. Poppies are for remembrance — and there’s a lot to remember in these parts.

Eighty years ago, in the opening minutes of June 6, 1944, the greatest amphibious assault in history began when a clutch of six gliders, navigating only by stopwatch, were cut loose over the Norman coastline and floated down upon the Bénouville Bridge over the Caen Canal and the Ranville Bridge over the Orne River less than a mile away.

The landing was picture-perfect. Today, three markers, mere yards from the Bénouville Bridge, commemorate the spot where the first gliders landed. Some 180 men disgorged from the silent airframes and quickly overpowered the German defenders of the two bridges, securing and holding the only crossings of the Orne north of Caen en route to the critical port of Cherbourg. Overlord, the Allied assault on Nazi-controlled Western Europe, had begun.

The capture of the bridges was a textbook coup-de-main operation, achieving its objective in a single blow. Two British soldiers were killed. I’ve read that the fate of the fifty German defenders is unknown. Later in 1944, the Bénouville Bridge was renamed Pegasus Bridge, after the depiction of Bellerophon riding Pegasus on the shoulder patch worn by members of the 6th Airborne Division of the British Army, which undertook the mission.

It was a quiet prelude to the cacophonous, multi-pronged assault that unfolded later that day — D-Day — as nearly 7,000 ships and some 4,500 aircraft suddenly appeared off the coast of northern France. In a matter of hours, 156,000 troops landed on five beaches — code-named Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword — across a massively defended fifty-mile stretch of coastline from Les Dunes-de-Varreville to the mouth of the Orne.

I can’t add anything new to the mountain of commentary on the D-Day landings or the domino-like collapse of the Third Reich that followed. Like others, I was struck by the now quiet ferocity of the German gun emplacements: the lowering concrete bunkers that still dot the landscape, some with the snouts of their 155-millimeter howitzers still pointing at the sky.

One of the most extraordinary sites is Pointe de Hoc at the western end of Omaha Beach. It was here that US Army Rangers scaled the 100-foot cliffs using rocket-fired grappling hooks and ladders. About 225 Rangers were involved in the initial assault. Seventy-seven were killed. One hundred and forty-eight were wounded.

Normandy is full of such numerological litanies: this many deployed, this many killed or wounded. It’s part of the study in contrasts that defines any major battleground. The contrast is heightened in Normandy, with its majestic natural beauty. In summer, the air is alive with the ensorcelling scents of wildflowers, the pulsing fecundity of the land, and the flinty beauty of its stone buildings, many dating from the eleventh or twelfth centuries.

I’m not sure which is more impressive, their longevity or the crumbling evidence of eventual decay that their lichen-crusted, pockmarked facades betray. The hulking reminders of vacated tyranny that dot the landscape can seem like little more than tourist props at this distance. All those rusted tanks, bent cannons and rotting casements can seem like nothing more than echoes of a canceled drama with doubtful relevance to the quotidian pressures of twenty-first-century life.

The three major military cemeteries in the area remind us how shallow that conclusion is. It’s often said that death dissolves all in an indiscriminate brotherhood of finality. That may be true. But no one, I think, can fail to notice the striking differences between the cemeteries of the three belligerents.

The German cemetery is a dark field of plaques, each set into a rectangular foundation of rough stone or concrete. At the end of the field is a large tumulus, a mass grave for some of the thousands who, in death, gave up their identity. The mood here is grim, almost Druidic, about this necropolis.

The atmosphere at the British and American grave sites is markedly different. It would be paltering with the truth to say that there was something joyful about their memorials. But there is, I think, something more affirmative about them. Visually, the fields of standing white headstones contrast markedly with the dour little plaques that fill the German cemetery. There’s also, especially in the American cemetery, an aura of power, victory, and religious triumph.

The prize for the best inscription goes to the stately memorial that fronts the British cemetery. The Norman duke, William the Conqueror, took off from these shores to subdue England in 1066. Now, the British helped to redress that assault. NOS A GULIELMO VICTI VICTORIS PATRIAM LIBERAVIMUS: “We, conquered by William, have liberated the fatherland of the victor.”

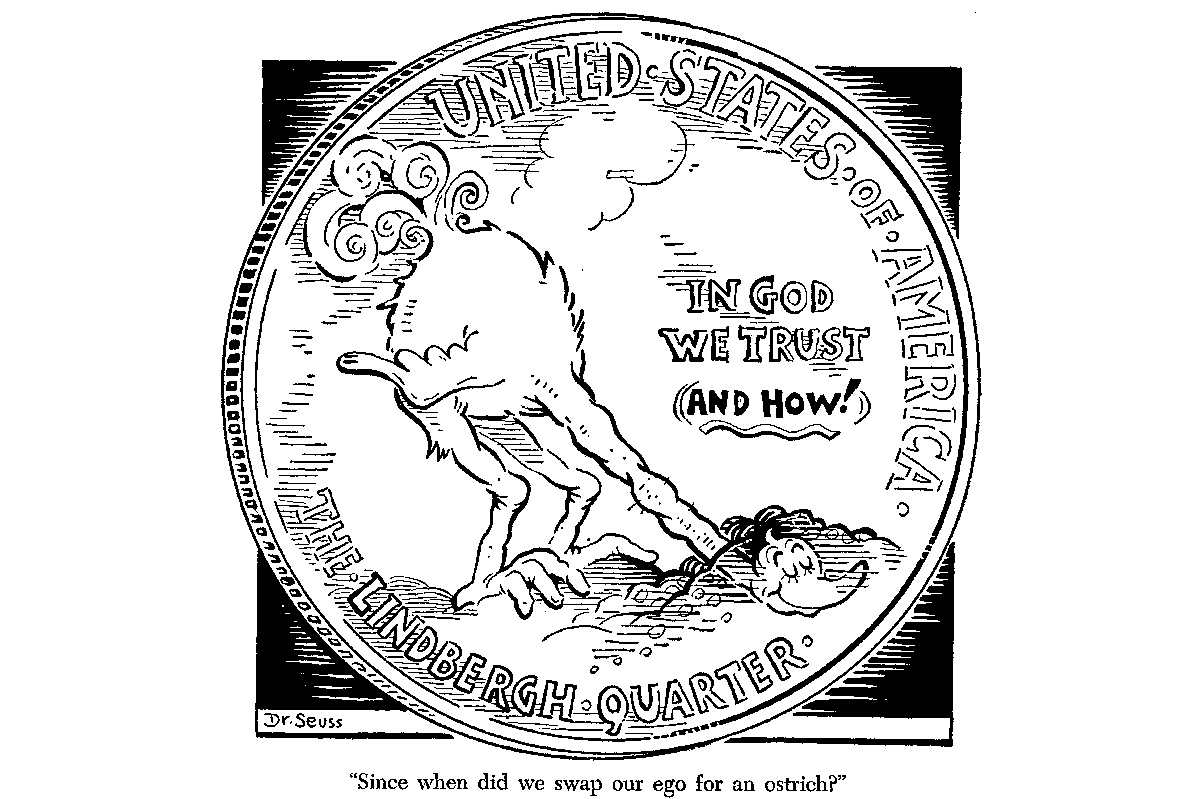

At the end of the day, however, what impressed me most about the story of D-Day, the Atlantic Wall and the Allied assault was the somber moral fact that stood behind and made Operation Overlord an existential necessity. As much as any conflict in history, this was a battle between the dark forces of tyranny and the forces of freedom. On this Memorial Day, it behooves us to hold fast to that recognition. The poet Christian Friedrich Hebbel got to the nub of the issue when he exclaimed: “What a vast difference there is between the barbarism that precedes culture and the barbarism that follows it.”

Leave a Reply