When hundreds of mostly African migrants escaped from the transfer center in Porto Empedocle, Sicily, last weekend and began roaming the town’s bakeries and shops begging for food, the mayor took to social media to explain. There were 2,000 migrants squeezed into a facility meant for 250, he told terrified locals. The conditions were inhumane. The repeated attempts to escape were inevitable.

On the island of Lampedusa, 11,000 migrants had arrived in the space of five days. There were 6,000 migrants in a facility meant for 600. The Sub-Saharan Africans were fighting with the North Africans. “To get food is a problem,” one migrant told a television interviewer. “If you don’t fight, you don’t have food.” Public transport was at a standstill as authorities commandeered buses to shift the migrants. Locals — and an increasing number of Italian politicians — refer to what is going on as an invasion. Migrant arrivals have doubled this year to 130,000 and the enormity of the crisis is about to shake European politics to its core.

However overwhelming the situation in southern Italy may look now, it is only the merest foretaste of the troubles that await. Europe’s population is shrinking, and fast. In countries where childbearing has been out of fashion for quite some time — Italy among them — each native generation is only about two-thirds the size of the last. Since Europe is rich and peaceful, migrants would be rushing to fill the void in any case, but Africa, especially south of the Sahara, is now growing at a rate never witnessed on any continent. Sub-Saharan Africa passed the one-billion population mark in 2015, but it is going to more than double, to 2.12 billion, by 2050. By then the population will be ten times what it was in 1950.

Italian politics already looks different to how it did a week ago. Italy’s Prime Minister, Giorgia Meloni, a fiery orator from the most Mussolini-sympathetic precincts of the country’s right, came to office promising a tough stance on immigration. But she has defected from the politics that brought her to power, ruling as a pro-EU moderate, even on immigration matters.

Meloni’s guest in Lampedusa over the weekend was the European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen. The two of them urge streamlining the policies of the EU “migration pact” passed in June. They envision better cooperation with Tunisia and a more efficient distribution of asylum seekers to all the twenty-seven European Union countries. “We will decide who comes to the European Union and under what circumstances, not the smugglers and traffickers,” von der Leyen said, adding: “The most effective measures to counter the smugglers’ lies are legal pathways and humanitarian corridors.”

Italian voters, of course, worry less that traffickers are lying to migrants than that they’re bringing migrants. Voters don’t want legal pathways and humanitarian corridors. They want a blocco navale.

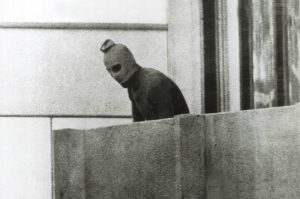

The blocco navale is the system that Italian politicians settled on after a huge wave of migrants from the war in Syria drove the world’s politics in a rightward direction. Remember? Pakistanis, Afghans, Iraqis and others joined the refugees fleeing the Middle East, and soon millions were converging on the EU. “Wir schaffen das,” proclaimed German chancellor Angela Merkel, meaning Europe could accommodate them.

She was only half-right. In Germany, the first national right-wing party in the country’s post-World War Two history entered state parliaments. In Britain, discontent with the EU mounted. In the United States, Donald Trump rose in the Republican primaries. And in Italy in 2018, a coalition of right-wing and left-wing populists took power. Interior minister Matteo Salvini pursued a policy of eliminating immigrant traffic altogether, collaborating with unsavory elements of the Libyan coastguard and battling pro-immigration foundations and quasi-autonomous groups in Italy’s courts. This briefly made Salvini one of the most popular Italian politicians of modern times.

Salvini is still on the scene, serving in Meloni’s coalition as infrastructure minister. If there is a road back to Italian voters’ hearts for him, this is it. “I do not rule out any kind of intervention,” he said, including the navy.

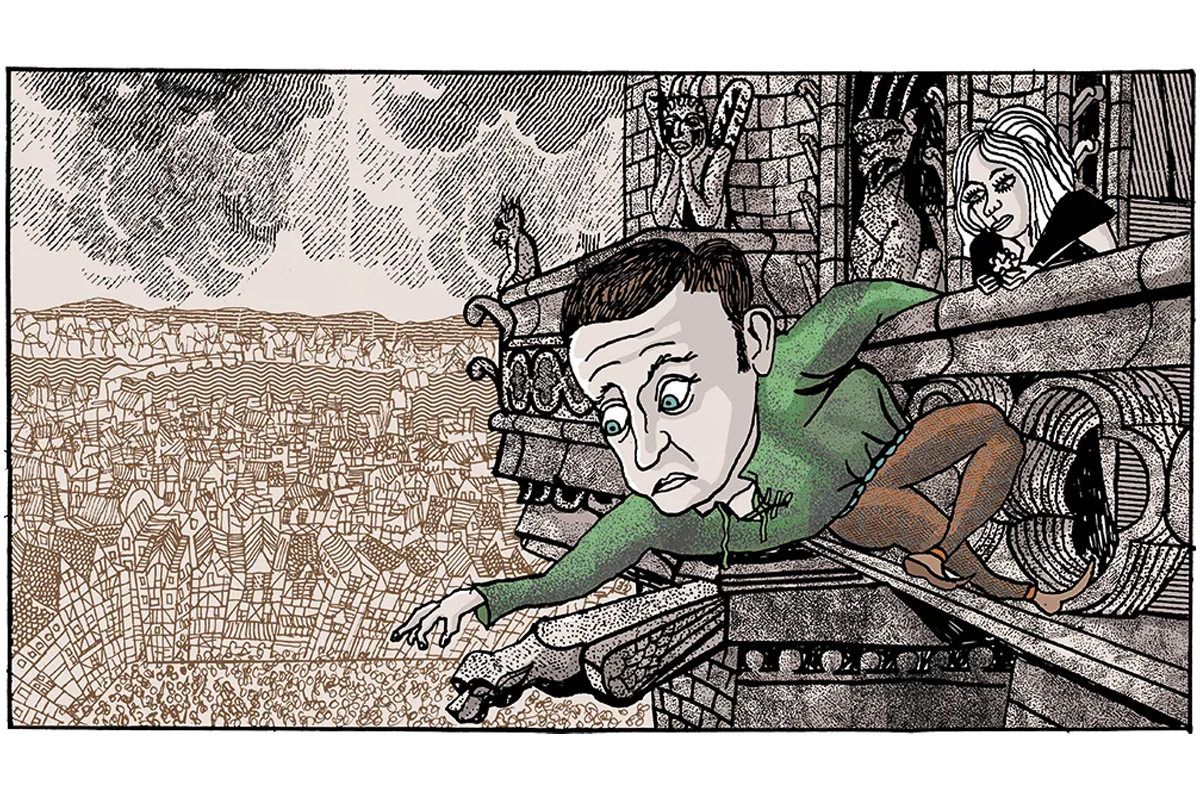

Complicating matters for Meloni is the matter of Roberto Vannacci, a clear-headed and intransigent general, who this summer published Il Mondo al Contrario (The World Turned Upside-Down), a defense of “normal” (his word) Italians against migration, gay rights and political correctness. It moved into the no. 1 spot on Amazon early last month and has not been dislodged since. As the migrant traffic has increased, Vannacci has been ever more present on television.

The problem with von der Leyen’s orderly bureaucratic approach is that it is not logical. There are really only two ways that Brussels can help a country in Italy’s position. One is to provide the resources to block the migrant traffic before it reaches Italy. But the EU is not made for that: it doesn’t have its own navy. Decisions on such external matters require a unanimous vote in the European Council, and migrants picked up in transit get brought to the closest port, which is often an Italian one.

A second way is to enforce a fair distribution of the migrants who arrive on Italy’s shores. But there are half a dozen European countries — Austria, Denmark, Hungary, Latvia, Poland and Slovakia — that rule out taking any migrants at all. Italy has been less than enthusiastic about offering such solidarity itself. Italian officials barely bothered to conceal that their laissez-faire attitude towards freedom of movement was to permit French-speaking migrants to find their way to countries where they could understand the language, and welfare-seeking ones to countries with more to offer.

A good deal of the problem revolves around a long-standing issue with the EU’s “Dublin Regulation,” which has proved to be unworkable year-in, year-out. To prevent migrants from converging on Germany, Scandinavia and other well-provisioned states, responsibility for feeding and housing them is supposed to fall on the country where they first arrive. But this merely gives a free pass to the northern countries, leaving the Mediterranean ones holding the bag. In November, Italy refused to grant landing rights to a ship called the Ocean Viking. The 230 migrants on board disembarked in Toulon and disappeared, to the fury of a certain part of French public opinion.

Jordan Bardella, president of Marine Le Pen’s National Rally party, has called on President Emmanuel Macron to pledge that “France will not accept one single migrant from the joint operation in Lampedusa.” There is a logic to this: designating a whole continent as the catchment area for migrants rather than two or three unfortunately situated neighboring countries would mean a larger number overall. It’s a pull factor. That is why Éric Ciotti, of the more “bourgeois” Républicains, speaks in terms that are not much different: “If France embraces the logic of sharing migrants,” he said recently, “it opens the door to even more massive arrivals.”

Everyone seems to feel this way. The 2015 Syrian crisis arose in a region, the Middle East, where population growth had long ago passed its peak. Africa, demographically speaking, is a bottomless well. The potential for radical disruption is consequently higher. So Austria has heightened surveillance of its border with Italy. Germany, which gets vastly more migrants than other states, has recently pulled out of an agreement to accept migrants from Italy — 400,000 new arrivals will have applied for political asylum before the end of this year, and patience with migration is running thin. Last weekend, mobs of anti-regime Eritrean exiles attacked a pro-regime event and the two groups battled it out in the streets of Stuttgart with iron bars, planks and pieces of concrete.

Alternative für Deutschland, the radical party that began focusing on immigration matters in 2015, has risen above twenty percent in polls nationwide. German voters tell pollsters that immigration is “Problem no. 1” for their country. Bavarian minister-president Markus Söder has called for an “integration limit” of 200,000.

The number of migrants who arrived in the UK in boats last year — 46,000 — looks like small potatoes in comparison with refugee flows in the Mediterranean. What is going on in Lampedusa now is a civilizational rather than a conjunctural problem. It is tied up in the West’s misplaced priorities and warped threat assessments.

Lampedusa was once an imperial frontier, a place where the free world and the third world were in communication. It used to be an asset for the free world; now that is less certain. Viewed by posterity, the invasion of Libya launched by Barack Obama, Nicholas Sarkozy and David Cameron in 2011, which opened a corridor for the large-scale trafficking of migrants, will probably be seen to have posed a larger threat to the “European way of life” than the invasion of Ukraine by Vladimir Putin last year.

In the long, withdrawing roar, European immigration policy will determine the politics of the next generation. There will be those (like the Salvini supporter who last weekend carried a sign reading “Give Lampedusa back to Africa”) who worry that there is little defense against the coming wave of immigrants. There will be those who propose (like the late French novelist Jean Raspail, author of The Camp of the Saints) that we fight them on the beaches. As the former French president Nicholas Sarkozy said last month: “The migration crisis has not even started.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.