If you want to be a prominent member of Congress in this day and age, the surest path is to become a hype machine for the ideological extremes of your party. Yet Nancy Mace gives no signs of responding to these tabloid incentives in conversation with her constituents. It’s an odd thing to say about a politician in 2023, but you might even find yourself taking her seriously.

In a Washington where the House of Representatives is dominated by GOP would-be pundits, including bomb-throwers such as Matt Gaetz and Lauren Boebert, the second-term Republican from South Carolina’s 1st district sounds like a politician from a different era. To walk away from Mace’s display of in-depth knowledge about shipping issues at the Port of Charleston, just turn the key in the pickup and hear Sean Hannity trying to talk Marjorie Taylor Greene out of her case for a “national divorce.” It provides an immediate, reorienting record-scratch: Greene and Mace may be in the same party, in the same Congress, of the same sex, but they might as well be members of two different species.

Mace is familiar with the downside of national divorce — her district includes Fort Sumter. Her explanation of why Greene and others engage in such discourse is straightforward: “Money,” she says. “It’s just about fundraising. Say the crazy thing, rake in the money and attention, move on to the next thing.”

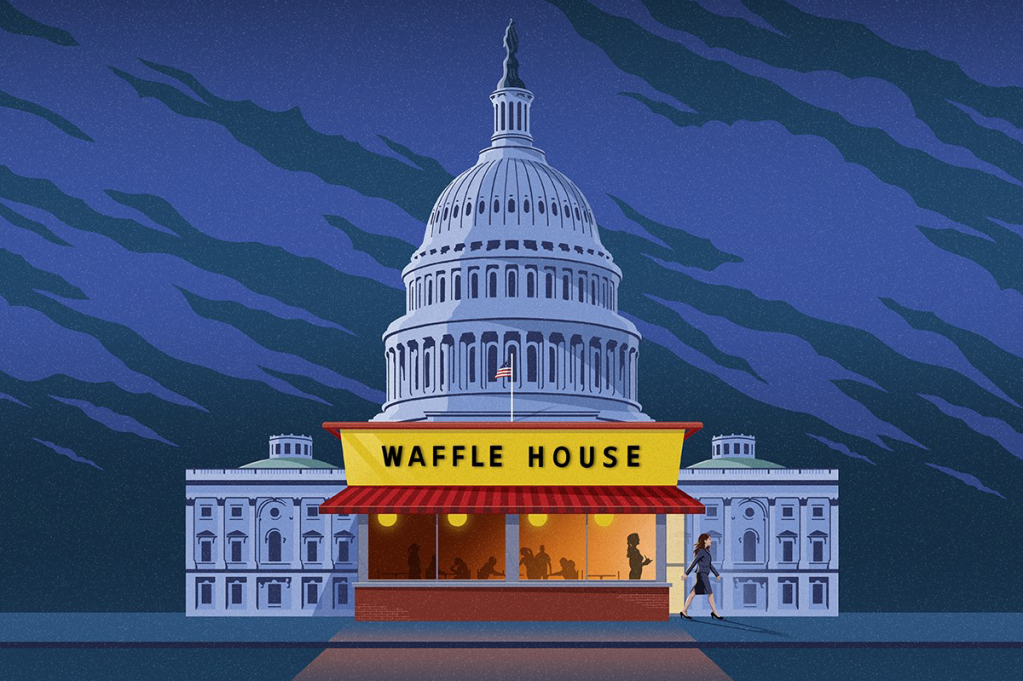

Mace is more interested in accomplishing what she can in a closely divided Congress, and wishes more members had similar priorities. “I feel like I’m approaching this job in a way that’s normal, socially sensible and fiscally conservative,” Mace told me over breakfast of eggs and hash browns (scattered, smothered and diced, in case you were wondering) at the Waffle House where she once worked as a high-school dropout. “I feel that’s where most voters are. But I feel like a unicorn. And I shouldn’t.” Hilton Head, the southernmost part of the 1st district, enjoys a rare combination of nation-beating rates of binge drinking and high credit scores — a collection of older retirees packs the bars for happy hour on an Ash Wednesday night but also are never behind on their bar tabs. Their considerations combine a lubricated form of social moderation, fiscal conservatism and an abiding pro-military patriotism — a combination Mace herself embodies.

On paper, Mace’s life looks like a tale of woe from the undercurrent of white working-class America. From a military family, she struggled as a teen with mental health as a survivor of multiple sexual assaults, became dangerously depressed on prescription medications, dropped out of high school, turned to marijuana for help and is about to enter her third marriage.

But hers is also a story of that type of Low-Country struggle turning into success. She overcame roiling opposition at the famed military academy the Citadel, where she became the first woman to graduate. In her 2001 book In the Company of Men, she credits the experience with saving her life. A single mom of two kids, a small business owner and real estate investor, she eventually became a member of Congress who bested a Democrat incumbent in a difficult district.

Mace’s ability to connect with her form of Waffle House populism is a chief reason she is another kind of unicorn: one of the rare incumbent Republicans to overcome the opposition of former president Donald Trump in her 2020 primary. Outlets such as Vanity Fair and the Atlantic condemned her for what it took to win that race — saying nice things about the policies of the Trump presidency to make up for her personal criticism of him after January 6, including posing in front of Trump Tower in New York and saying the former president “made America safer.” But Mace effectively chose to stay in Washington and fight, instead of setting herself aflame for the minor benefit of slow-witted praise from CNN, like Adam Kinzinger and Liz Cheney.

Her path has not been without extreme opposition. A thread of trauma runs through Mace’s life. She writes in her book of being slut-shamed as a teen, of mailed-in threats to her life and her family during her time at the Citadel (“And this was a lot harder than email these days; you actually had to go to the post office and buy postage to tell someone you hated them back then!”) and a bomb scare at her graduation. She has endured doxxing and stalkers aplenty since her rise to Congress. She carries a gun with her at all times, and is well aware of the flak endured by conservative women on the national stage.

The test now for Mace and those few younger members more interested in legislating than in fundraising via media-hit will be what they can get out of what’s widely expected to be a do-nothing Congress. Mace runs through a litany of her legislative priorities — Ukraine spending, the national debt and deficit, military and veterans’ reforms, women’s issues ranging from abortion to rape kits to birth control, and local environmental and business grant concerns. For a junior member with a small cadre of young staffers, it’s a lot to bite off. But she’s already gained a reputation for holding witnesses to account in congressional hearings, demanding they respond to their own words and tweets in moments that have gone viral for the right reasons.

For Mace, the women’s issues she intends to prioritize in the coming year are a core element of her complaints about her party in the post-Dobbs era of abortion lawmaking. She shakes her head with bemusement as she shares that the pro-life groups in Washington won’t even talk to her any more after she became a leading figure in the push for over-the-counter birth control. She became one of eight Republicans to vote with Democrats to federally protect access to birth control, and even donned a jacket with a message taped to the back: “My state is banning exceptions. Protect contraception.”

“We completely botched the response to the overturning of Roe,” Mace explains. After the Supreme Court decision, she charges, Republicans ran away from the issue, allowing extremists opposed to the rape, incest and maternal-life exceptions supported by most Americans to seize the conversation on the right, and for the left to claim, not without justification in her view, that the GOP couldn’t be trusted not to ban birth-control pills. Mace sees the DC consultant class as scared of the issue, and male politicians as clumsy in their language, closing off women and political independents who need to hear clear stances and empathetic policies.

In the closing days of her own 2022 campaign, her Democratic opponent was running heavily on the abortion issue, and Mace credits her choice to engage on the issue and push back as the reason she ended up winning by fourteen points — far more than polls suggested at the time. “We have to be in favor of exceptions, of birth control access, and of more support particularly for single moms if we’re going to win independent voters,” Mace says.

The constituents that show up to Mace’s Hilton Head events reflect this independent streak, with a populist distrust for Washington. They’re proud of their unicorn — one couple recommends a recent interview she did on Firing Line, saying they show it to all their friends as an example of what a member of Congress should be like. Attendees emphasize issues of inflation and exorbitant spending under President Biden, loathe the lack of accountability for botched Covid policies, and express concern that the war in Ukraine is costing too much. Mace agrees — fresh from the Munich Security Conference, she says she thinks Ukraine needs faster delivery of weapons systems, and believes that the longer the war continues without a clearly defined endgame, the more Russia and China will be emboldened.

Mace acknowledges that the GOP is still in the early stages of a new understanding of its foreign policy priorities in the post-Bush, potentially post-Trump era where a lot of old labels no longer make sense. “I’m not a neocon, that’s ridiculous — I was opposed to the Iraq War,” Mace tells me. “But we need to be clear with voters about what will happen if Ukraine falls, and if China takes Taiwan. There’s a direct impact here at home. We needed to make Ukraine stronger before the war, and we need to make Taiwan a tougher porcupine.”

For the Republican Party writ large, there’s a real question of how much this South Carolina, suburban-friendly approach can translate on the larger stage. Presidential candidate and former South Carolina governor Nikki Haley is a friend and constituent of Mace, and so is potential candidate Senator Tim Scott — Mace and Scott attend the same church. When asked if their brand of social-policy centrism can translate in a time of heated culture war, Mace seems unsure: “They’re both great people, they’re both great leaders — it’s for the voters to decide whether that’s what they want right now.”

Mace herself is more hopeful for the party than some others, at least in the long term. She’s concerned about delivering as strong an agenda as possible in a divided Congress, but also sees the nation’s leadership class as ripe for a long-overdue generational change — one that gets back to being about the policy priorities of the populace, not just interest groups and pundit-representatives that throw out shiny objects like “national divorce.” She even holds on to a dream that the Republican Party will be the first to elect a woman president. “After 2024, a lot of things will be possible that aren’t today,” Mace says. It’s getting past the next two years that may prove the real test for Republicans like her.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2023 World edition.