One of the most famous lines from the classic 2002 romcom Sweet Home Alabama has leading lady Reese Witherspoon incredulously asking a redneck hometown friend, “You brought a baby… to a bar?” I encounter that incredulity frequently, every time I cart my kids to work events, including those at bars. But a book tour? This was a new one. A book tour with a baby is hard, but babies (and kids) are worth all the hardships. As Scrubs’s wise Dr. Kelso once explained, “Nothing that’s worth having in life comes easy.” That’s a mantra in our home as we wade through the hard times, and it’s a lesson we impart to our kids as we endeavor to raise them into happy warriors and resilient and caring adults.

During a Q&A my co-author Karol Markowicz and I filmed ahead of the publication of our new book, Stolen Youth: How Radicals Are Erasing Innocence and Indoctrinating a Generation, we were asked our motivation for writing it. “Sleep,” was my one-word answer. I wasn’t getting it, so I might as well be writing with all that free time. Some advice: don’t sign a book contract if you have a newborn. Don’t get pregnant while you’re writing a book, either. Definitely don’t do both and have two babies in seventeen months while you’re also writing a book.

When we travel as a family of seven (or now, with the birth of our sixth child, a party of eight), we are traveling very differently than I have on my mom-and-newborn book tour. I’m used to being the snack concierge for a gaggle of my own kids flying discount airlines; this time around I held a sleepy baby while being waited on in first class.

The first time I flew first class was with my mother when I was a teenager. When we got our boarding passes, we discovered we would be seated separately. My mother objected and explained to the gate agent that as an insulin-dependent diabetic and an epileptic, she had to travel with me to administer her insulin shots and be on hand to assist with an unexpected seizure. The only remaining side-by-side seats were in first class, so that’s where we ended up. My mother’s sob story was all true, but, with free booze flowing, my diabetic and epileptic mother proceeded to get wasted. By the time we landed, she was in no position to drive us home. I took our phone book to a pay phone and called friends with a license until I found one available to pick us up and bring us home from the airport. Weirdly, I look back on that flight with fondness. The circumstances of that trip were so quintessentially my mom, whom I lost too soon, just a few years after that boozy flight.

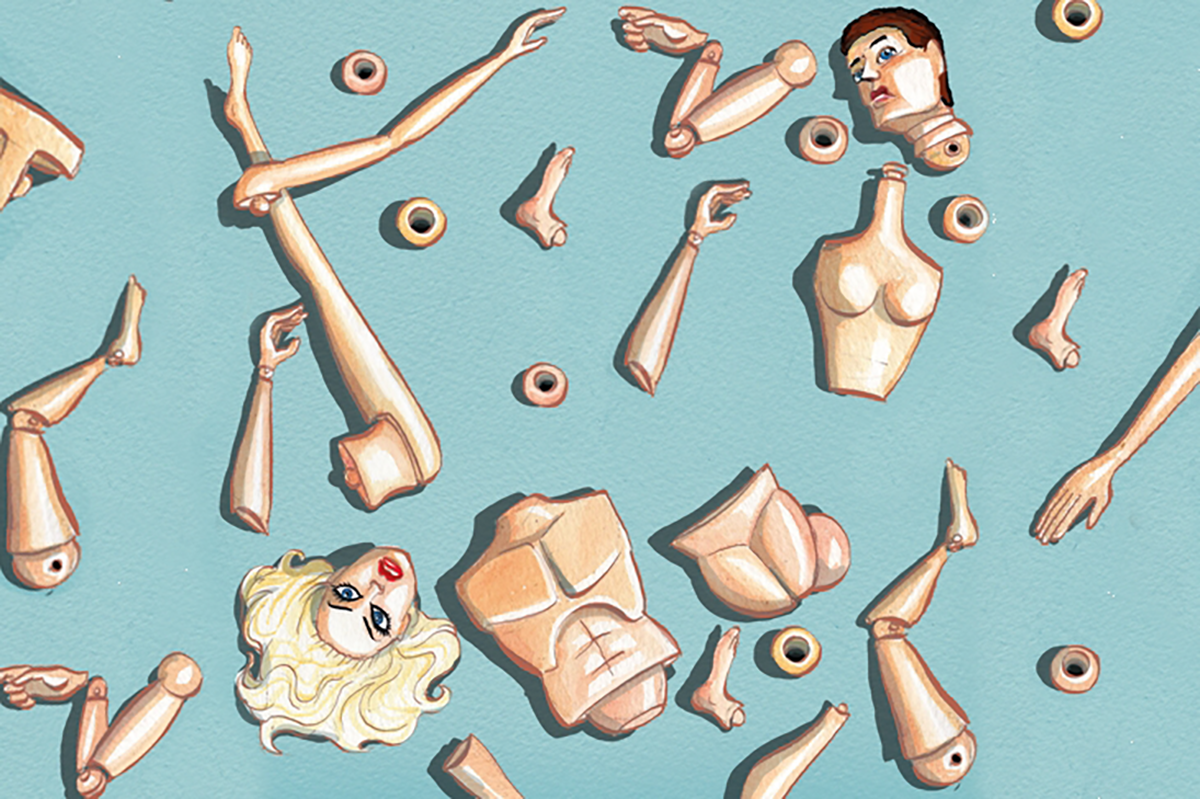

With Covid school closures and mandates, with transgender ideology and the woke war on resilience and happiness, I find myself wondering how I might have fared were I a child today. In fact, that hypothetical would be a more serious, and honest, answer to the question about my motivation to write this book. It was by writing Stolen Youth that I came to realize that this assault isn’t just an attack on innocence, but on resilience as well. Woke revolutionaries can’t succeed in remaking our entire society if kids are happy and resilient. They can only succeed if kids are basket cases. And basket cases are what kids are turning into. Our culture not only tells kids that boys can be girls, but that biological boys can be on girls’ swim teams and in their locker rooms, and if they object, they’re bigots. Girls are told that nobody should be allowed to make them feel physically uncomfortable, that we should believe all women, until their bunkmate at summer camp shows up with facial hair.

Were I living that tumultuous time period of my life now, I’d have had a therapist fomenting resentment towards my mother for being so irresponsible. I’d likely not have had a therapist who told me, “Stop self-identifying as a victim unless that’s how you want to live your life.” Perhaps I’d have had a therapist suggest, as I heard countless times from parents I spoke to for the book, that the root cause of my unhappiness was actually my gender identity instead of my life circumstances.

Would I, a tomboy with a broken home and heart, have been susceptible and vulnerable enough to listen? I shudder at the thought that I might have been talked into hormones and physical modifications that could have rendered me infertile or unable to breastfeed. These are the thoughts that haunt me, and what ultimately motivated me to write that book and bring that baby on my book tour. I’ve got an hour left on this flight and a sleeping baby in my lap, and I’m going to get in a power nap.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2023 World edition.