Americans have never been sure of their standing in the world, and the world has never been sure of Americans’ standing. In their first century as a nation, Americans believed that their principles made their civilization not just different but also better than Europe’s. Meanwhile, the intellectual and political leaders of Europe were unconvinced that America was a civilization at all. In their second century as a nation, other, older civilizations were obliged to admit that Americans were not just different: they were better at modern life. The Americans achieved this recognition first by the force of their industrial and military power, and then by the flattery that other civilizations could become equally forceful and seductive by adopting the American way of life.

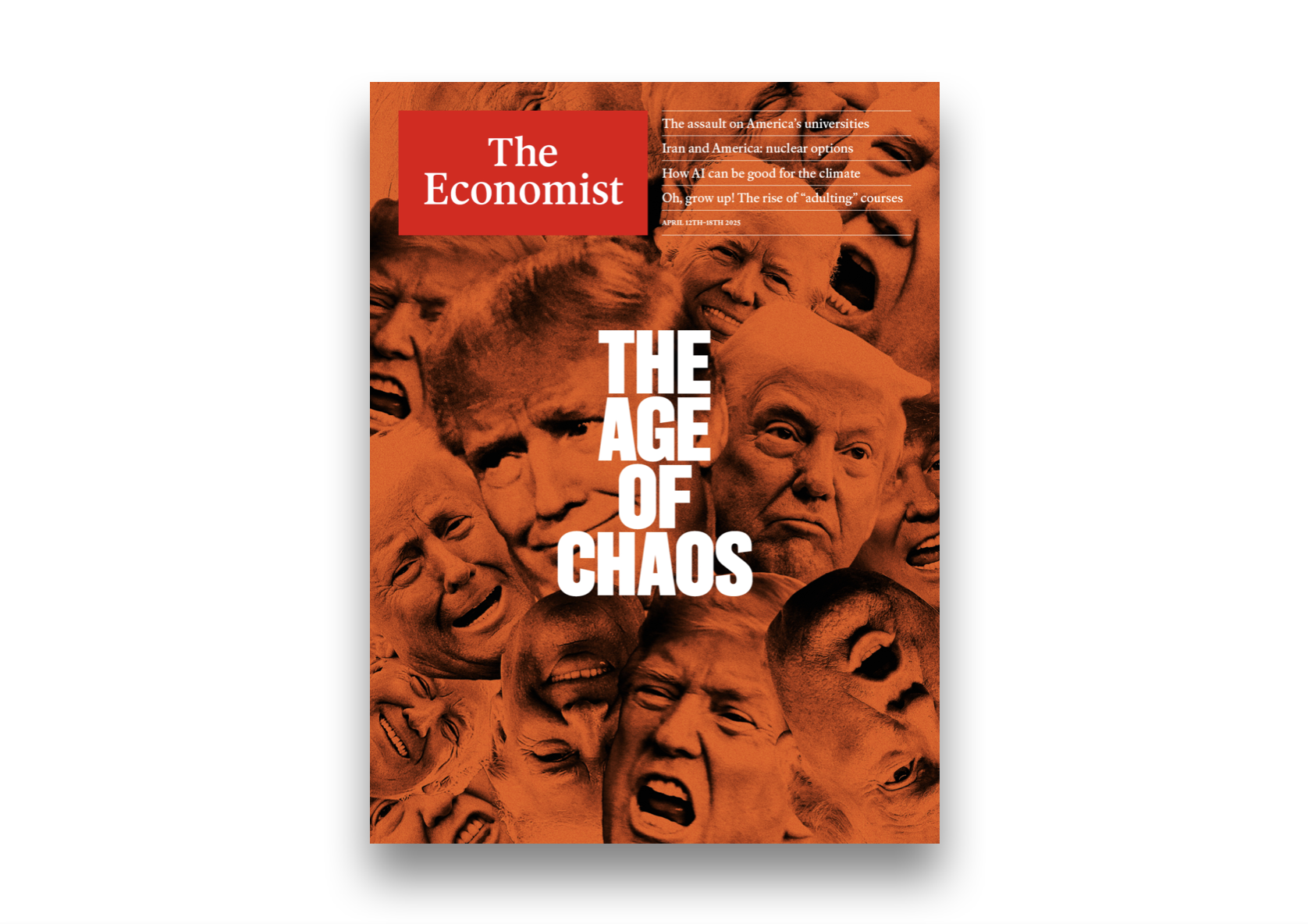

As we stumble to the halfway point of the third American century, this mutual ambivalence about the global purpose of Americans has intensified to open rancor. Three factors are driving the fallout: global geography, global economy, and domestic politics. Until now, the United States benefited from its geographical location. Americans were sufficiently adrift in the Atlantic to develop their own ways of life. When America did become a global power, the battlefields were so distant that its cities and civilians were safe. But then the motor of global productivity shifted to Asia. The logic of markets and diplomacy is following that action.

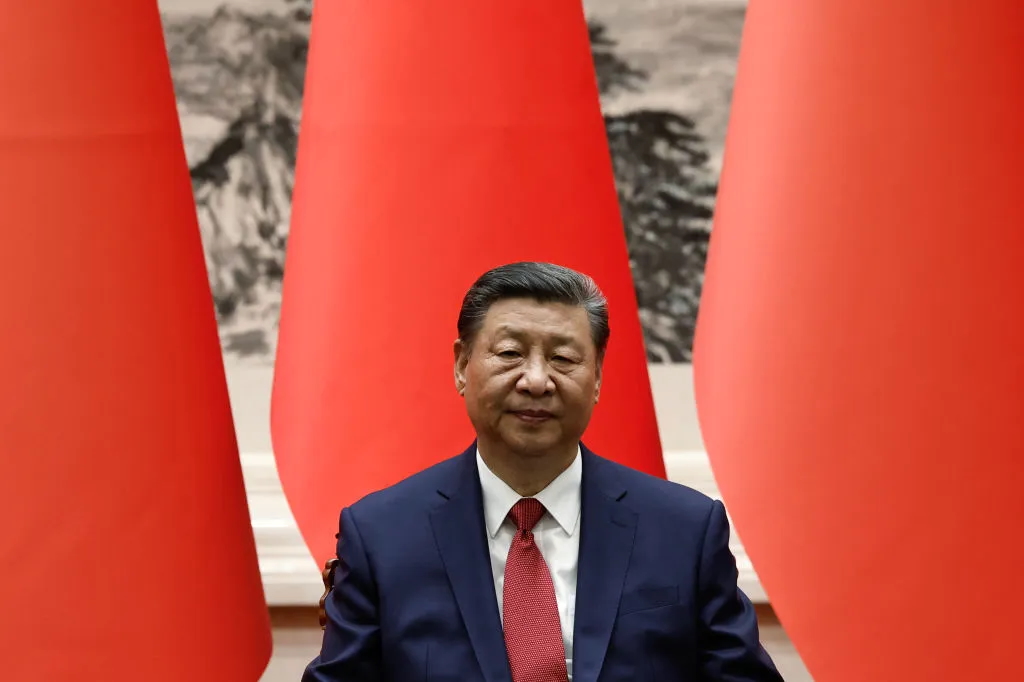

The center of geopolitical gravity is now somewhere between central and western Asia, and the arena of likely conflict has moved from the North Atlantic to the Pacific. Where Americans once retained their connection to older civilizations through connections with a Europe that, if frequently disappointing, was at least comprehensible, they now face an incomprehensible rival across the Pacific that seems to embody the self-sustaining convictions of an old civilization with the aggressive confidence of a new one.

We all know that sooner or later, the United States will face a reckoning with China that will test the sense of American strategy and the substance of American alliances. It will probably happen sooner than expected, given how the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated these trends. This reckoning might also test the quality of American weaponry; the military-industrial complex, once feared as a threat to American liberty, now seems like one of the two surviving guarantors of American independence. If the reckoning happens later, it will also test the credibility of the other surviving guarantor of American independence, the US dollar.

Despite the urgency, the political class and its followers in the think tanks and the academy have failed to arrive at a consensus about the nature of the challenge and the objectives that might sustain American civilization. American foreign policy is now subordinated to the bitter binaries of domestic politics. It is inaccurate to say that party politics used to stop at the water’s edge; the split between internationalists and isolationists in the 1930s, for instance, shook out along party lines. Still, the bipartisan consensus of the Cold War and the fat years of the 1990s disintegrated in the failures of the War on Terror and the lean years after 2008. Republicans and Democrats no longer agree to go to the water’s edge together. Instead, domestic differences lead to a blood-dimmed tide in the shallows.

The Republicans had their big wars under George W. Bush, the Democrats had their little wars under Barack Obama, and the American people lost them all. The Republicans now have their preferred regional clients (India, Britain, Israel, the Gulf Arabs) and the Democrats have theirs (France, Germany, Iran). The Republicans have their enemy (China) and the Democrats have theirs (Russia). Meanwhile the rest of the world, baffled and insulted, can now release its repressed resentment of the Americans: so loud, so uncouth, so convinced of their crude certainties, so unfairly able to enforce their habits and values on everyone else, so insistent on being heard but so incapable of speaking in a single voice.

Republicans and Democrats, as if confirming the resentment, remain faithful to the doctrine of American exceptionalism, which is to America’s grand strategy as pre- destination is to Calvinism: an idea so original that it remains an organizing principle even when no one is sure what it means. The Republican interpretation of this doctrine holds that American civilization is better than other civilizations because it is different. The Democratic interpretation is that American civilization is different, and that, while it could be better, it is worse.

Therefore the Republican rejects external systems which seek to reduce the difference of American life — the United Nations, the International Criminal Court, the metric system — while the Democrat seeks to import them. The Republican seeks to repel these noxious foreign imports before they can reduce Americans to the unexceptional status of those formerly free peoples who have consented to bind themselves in red tape, legal commitments and a sadly diminished view of human freedom and potential.

The Democrat reckons these imports might upgrade the American from his freedom-obsessed ignorance and integrate the US into the global order. To which the Republican responds that what matters is not the global order, but who gives the orders. Thus Republican exceptionalism conditionally accepts external systems which promise to sustain the difference of American life: Nato, the UN Convention on the High Seas, the copyright system.

The result is that the US now has two foreign policies. We are alert to traditional symptoms of imperial blowback such as intrusive surveillance, militarized policing and the appearance of new immigrant groups seeking refuge in the very state which demolished the one they were born in. But the real danger in the American case comes from what we could call imperial ‘blowout’: the projection into foreign affairs of domes- tic ideals of democracy and domestic discord about its effects.

This in turn derives from an unwillingness to recognize the imperial nature not just of American power in the world, but of the American state itself. As Thomas Jefferson hoped, the American state functions as an ‘empire of liberty’.

American foreign policy has become more explicitly imperial and less interested in freedom. The president’s war powers, though modified, mean that democracy stops at the water’s edge. Republican or Democrat, everyone agrees that the most successful episodes in American foreign policy, the maintenance of the World War Two alliance and the Cold War alliance, were managed by unelected bureaucrats: ‘Wise Men’ like Dean Acheson, Averell Harriman and George Kennan. When the domestic system works properly, the terms of foreign engagement are left to the experts. Foreign policy only becomes a democratic issue at times of crisis, as in the 2004 elections, which were defined by the 9/11 attacks and the War on Terror, and the 2016 elections, when Donald Trump accurately exposed how post-1990 policies — invading the world, inviting the world — had created an imperial blowback.

Americans are constitutionally incapable of admitting that they are an empire because their nation was created in a revolt against an empire. They see themselves as Nature’s democrats and, to be fair, they socialize like them too. The rest of the world is often inspired by this founding story and the democratic habits it inspires, but it has no doubts about whether America is an empire. The rest of the world also understands the exceptional potential and achievements of American democracy. This is why Europeans adore the American leader who appeals to European idealism about democracy — and why the Germans, who effectively destroyed European democracy in the early 20th century, responded so avidly to the ideals of JFK and Barack Obama. It is also why the rest of the world switches so quickly from admiration to contempt when an American leader states the national interest too bluntly while showing a preference for ketchup with steak.

The problem, then, for both Americans and everyone else, is that the traditional habits of American democracy are incompatible with the traditional goals of American foreign policy.

The good news, which is also the bad news, is that the decay of American democracy is rapidly resolving that incompatibility. The forms of the democratic republic survived into the middle-class society of the 1950s, but since then American society has mutated into the classic imperial society. An oligarchy and a credentialed client class rule a populace that is educationally and economically impoverished and functionally disenfranchised through the manipulation of the bureaucracy and the courts.

There are no exceptions to the laws of historical gravity. Americans are arriving at the juncture where Gibbon began his history of Rome. The republic has become an empire, and the empire no longer seeks to acquire new territories, but to consolidate its advantages. The ‘image of a free constitution’ is ‘preserved with decent reverence’, and the senate appears to ‘possess the sovereign authority’, but ‘all the executive powers of government’ have ‘devolved on the emperors’ and the bureaucracy.

It is because of this domestic transition from republic to empire that the contours of a new bipartisan consensus may be emerging. The neoconservative delirium may well have been the last moment in which the American impulse to democratize coincided with the means and the desire to do it in the governing class. Obama’s admission of defeat, that ‘the world is what it is’ and that the older civilizations will only Americanize their habits, not their hearts, marks a retreat of American democracy from the field of foreign policy. Trump’s ‘transactional’ dealings are the lowest common denominator of the realist school, and so likelier to succeed than the highest of aspirations.

The era of blowout, the American exception in foreign policy, is over. The ideals of the democratic republic could not bear the retorts of reality from beyond the borders. America’s future dealings with the world that refused to Americanize may be happier than its recent past. How Americans feel about their dealings with their own governments is another matter.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2020 US edition.