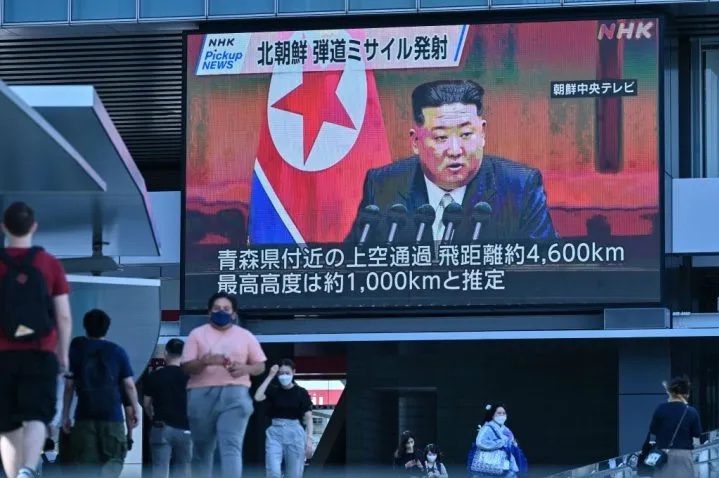

Silence is not a common feature in the North Korean regime’s playbook, and this year is no exception. Only this past week, North Korea’s flurry of ballistic missile launches has been complemented by a cornucopia of threats from senior officials — including Kim Yo-jong, the sharp-tongued sister of Kim Jong-un — who have upped the ante in their anti-US rhetoric.

The ruling regime repeated that dialogue with the United States is off the table. Not only that, the North Korean defense minister also warned that the deployment of a US ballistic missile submarine — the USS Kentucky — to South Korea could “fall under the conditions” for the isolated state to use its nuclear weapons.

One area in which North Korea has refrained from issuing its notorious bombastic braggadocio, however, is in relation to the fate of a US soldier, Private Travis King. Over a week since he unexpectedly crossed the inter-Korean border, the regime has remained tight-lipped on the subject.

Earlier this week, the United Nations Command, which oversees the Joint Security Area — where King made his dash — announced that “delicate talks” are ongoing with its North Korean counterparts. Just as with any information on King’s whereabouts and fate, the frequency and content of these conversations remain mired in ambiguity.

What has become less murky, however, is the story behind King’s getaway. Having faced disciplinary action while stationed in South Korea, his cross-border sprint was likely an impulsive, irrational decision. Although King is not the first to voluntarily venture into North Korea, the incident has occurred at a tense geopolitical time, with North Korea shunning any political engagement with South Korea and the United States.

Most defections of US soldiers into the hermit kingdom occurred following the ceasefire that halted the Korean War on July 27, 1953. Two of the most infamous defectors, James Dresnok and Charles Jenkins, fled to the North in succession in 1962 and 1965. Both men became propaganda tools, playing American villains in North Korean films, some of which were directed by the film fanatic Kim Jong-il, son of the then-leader, Kim Il-sung.

Even if Pyongyang’s past treatment of US citizens might shine some light as to King’s possible future, his case remains somewhat unique. In contrast to the tragedy of Otto Warmbier — who was returned comatose to the United States in 2017 — King was neither captured nor accused of political crimes whilst on North Korean territory. With its borders closed since January 2020, there remains a slim chance that North Korea could, after a month or three, release the serviceman following a spell in coronavirus-induced quarantine. Doing so would relieve it of another foreign policy burden.

But we should be realistic, which often means being pessimistic. These are early days. No possibility can be ruled out when dealing with this delinquent state. The dynastic Kim regime’s foreign policy negotiating strategies have long-been premised on getting what it wants, when it wants it. Pyongyang could exploit the timing of the incident to its favor.

It cannot be ruled out that the North may be intentionally keeping the US and its allies in the dark as it celebrates the far-from-jubilant platinum anniversary of the Korean War Thursday. As the North Korean narrative goes, which it repeats ad nauseam, it was Pyongyang who catalyzed the “ignominious defeat” of the “US imperialists” during the war. Thursday’s military parade in Pyongyang will also be in full view of Russia’s minister of defense, Sergei Shoigu.

After the celebrations are concluded, it is likely that King may become a bargaining chip, albeit not a hugely useful one. Beyond nuclear weapons, the regime’s never-ending thirst for money has been anything but quenched. A cash-for-human exchange accompanied by a visit of a high-level US emissary has been a common past North Korean tactic for releasing captured US citizens. How the government might justify such a visit given its border closures remains to be seen.

Yet, North Korea could also continue to resist dialogue with the United States and release King for a smaller benefit — perhaps as a quid pro quo for more docile US and allied responses to the North’s increasingly belligerent provocations. We should, of course, be wary of making links between such a diverse range of issues, not least King’s crossing and North Korea’s nuclear ambitions. But the fact that a spate of missile launches followed the King incident is hardly a coincidence.

At the end of the day, King remains a citizen of North Korea’s “hostile” archenemy, a state which the government has always claimed is plotting to overthrow the regime and start a war on the Korean Peninsula. As the deputy commander of the UN Command, Lieutenant General Andrew Harrison, aptly but frustratingly put it: “None of us know where this is going to end.” It is not just where, but also how and when.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.