When dealing with North Korea, it’s important not just to look at what the regime’s says about its present and future policies. Arguably more important is what the regime doesn’t say. Sometimes we might need to read between the lines.

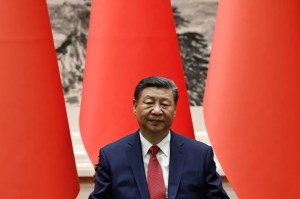

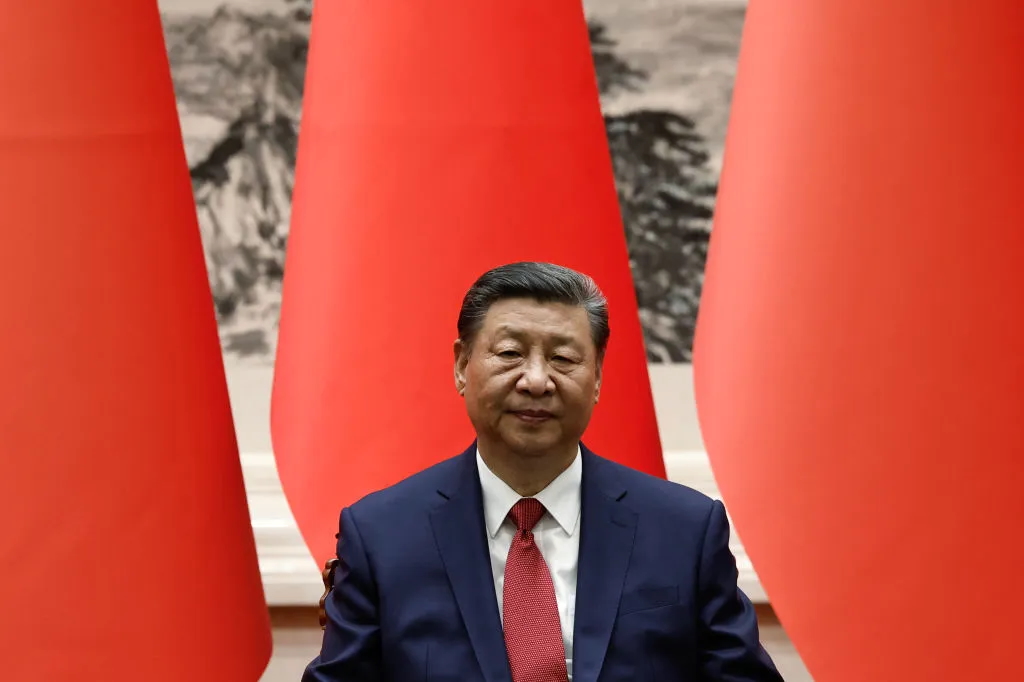

The two meetings between Kim Jong-un and Vladimir Putin within the space of a year indicate that the pair’s bromance is more than just for show.

Russia’s relations with North Korea look to be on an upward trajectory after the signing of a “comprehensive strategic partnership” between Kim and Putin. The mutual defense pact, where each side agreed to assist the other in the event of any external aggression, went far beyond a mere affirmation of ideological solidarity. Only last week, senior North Korean military official, Colonel General Pak Jong-chon, made clear how North Korea would “always be together with the Russian army.” Repeating Putin’s own words, Pak threatened a “new world war” with “the worst-ever consequences,” including a Russian retaliatory strike, if the United States continues arming Ukraine as part of its “confrontational hysteria against Russia.”

It is nothing new to see the North Korean regime invoke the language of war in its rhetoric. Even in 1993, before the country acquired nuclear weapons, the soon to be leader Kim Jong-il declared that the Korean Peninsula was in a “semi-state of war,” after the United States and South Korea had conducted joint military exercises. During the Obama administration, the euphemistically-named “Guardians of Peace,” a North Korean state-sponsored cyberwarfare group, threatened terrorist acts on the United States if cinemas proceeded to screen the Seth Rogan film The Interview which mocked the hermit kingdom. Earlier this year, Kim Jong-un ominously threatened that North Korea’s nuclear weapons were not just for defensive purposes, but that it could resort to offensive use in the event of any war on the Korean Peninsula.

What is concerning about the present-day, however, is that North Korea now has mutual defense pacts with both Russia and China. The latest treaty signed between Kim and Putin made clear how the Russia-North Korea relationship is not just a cash-for-artillery exchange between two anti-western states. North Korea furnishes its Cold War patron with millions of artillery rounds and short-range ballistic missiles. In return, Pyongyang gets cash, but also food and military technology and knowhow.

In addition to physical technology, recent reports in South Korean media have raised the possibility of manpower being sent to Russia from North Korea, both to aid reconstruction in the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics, and for the battlefield in Putin’s ongoing war.

With the fourth-largest standing army in the world, amounting to 1.3 million active military personnel — out of a total population of 26 million — North Korean society is highly militarized. Mandatory military service lasts for between ten to thirteen years for men, and seven years for women.

Both Pyongyang and Moscow have been reluctant to confirm or deny any such possibility. Nevertheless, if North Korea were to send engineers, soldiers, or construction workers to these Russian-occupied territories, it would certainly not be out of line with its foreign policy stance. Only five months after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, North Korea joined fellow rogue states of Russia and Syria in recognizing the “independence” of the so-called republics of Donetsk and Luhansk. Ukraine subsequently severed its diplomatic relations with the DPRK.

Quantity, however, does not equate to quality. North Korea may have strength in numbers — both in terms of armed forces and, of course, nuclear weapons. But compared to its neighbor south of the Demilitarized Zone, Pyongyang’s forces are less well-trained, and reliant on conventional capabilities that are often from the Soviet-era. As the Pentagon’s press secretary aptly put it, any North Korean military personnel sent to Ukraine would simply be “cannon fodder.” This description is not inaccurate. Yet, it is certainly concerning for international relations. We do not know for sure many such personnel Russia will require; how many North Korea will be willing to send; and what Russia will give the North in return. It was perhaps expected that the South Korean prime minister has said that South Korea might “adjust” its aid to Ukraine, given the strengthening North Korea-Russia cooperation.

The lack of explicit details about the deployment of North Korean troops or engineers to assist in Putin’s war, at present, is frustrating. But we must remember that such silence is a tried and tested part of North Korea’s strategic behavior. Ever since the creation of the North Korean state in 1948, tactics of lying and deception have formed part of the Kim regime’s playbook, across its three generations of leadership. Much like North Korea’s launching of ballistic missiles, these tactics are not going to stop anytime soon. Nothing can be ruled out.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply